As summer ends, more than 50 million American children are returning to school hoping for quality teachers, up-to-date textbooks, and working bathrooms. In this election year, candidates running for every office from president to local school board trustee debate the quality of the education being delivered and the best public policy for improving it. Much of the political fireworks are sparked by debates over the role of the marketplace in publicly funded education, the effectiveness of testing as a mechanism for improvement, the Common Core curriculum, and teacher unions. Very little attention is directed toward debating why school funding has decreased and what the effects will be of spending less on our children.

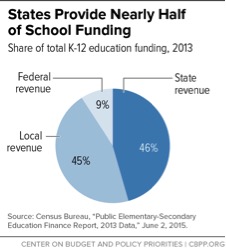

The size of our annual school budget, more than $630 billion, blinds us from seeing that our investment in public education has been decreasing since 2008. Many of the headlines in recent months have focused on the role of the federal government in public education, but when it comes to funding our schools, it contributes only a small portion of the total national school budget.

States and local bodies shoulder the major share of the financial load. Their ability and willingness to fund schools, combined with decisions to shift funds from schools to businesses and other priorities, determine how well our schools can fulfill their promises.

When the national economy hit bottom in 2007 and 2008, both state and local funding streams were under attack, and education funding was pushed downward. The federal government did step in with increased funding, allowing states to ease the recession’s impact on education. But as the economy improved, a gridlocked federal government eliminated these emergency funds, and states and local governments faced the challenge of recovery on their own.

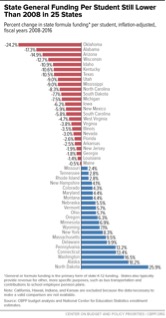

Left to their own resources, most states have chosen other priorities and not restored their funding to pre-Great Recession levels, even as school populations have increased and the need to strengthen schools has become more evident. According to a study of school funding published in early 2016 by the Center for Policy and Budget Priorities:

- Twenty-five of the 46 states with data available are providing less general aid per student this year than in 2008.

- In seven of those 25 states, the cuts are 10 percent or more.

- In three states—Oklahoma, Alabama, and Arizona—the cuts are 15 percent or more.

The reasons that states have not chosen to restore funding levels vary. In some states, the economy has not yet recovered and their tax revenues remain constrained. For others, other budget needs are seen as more critical, such as Medicaid and underfunded public pension plans. For others still, it is a matter of political philosophy: Government should be small, taxes low, and efficiencies are there to be found. Whatever the reasons that many states keep their contributions to education depressed, the burden of meeting the needs of children is falling more heavily on local resources in a very regressive manner.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

To make matters worse, many states and cities have chosen to prioritize tax incentives for businesses in the belief this will spur economic growth. In Chicago, according to blogger Scott Klinger, “Last year, one subsidy program alone cost public services $461 million. Meanwhile, the city’s schools are facing a budget that is $140 million less than they had last year.” Chicago’s schools were only able to operate last year by borrowing hundreds of millions of dollars and needed to lay off 1,000 people in teaching and support staff positions.

Bruce Baker, a school funding scholar at Rutgers University, has described how a dependence on local funding affects educational equity.

You’ve got highly segregated rich and poor towns. [They] raise vastly different amounts of local revenue based on their local bases, and [the state] really doesn’t put much effort into counterbalancing that.

Last spring, NPR made Professor Baker’s words quite vivid as it described the budget reality of two suburban Chicago districts with very different budgetary realities. The Chicago Ridge School District is able to spend $9,794 per student, well below that year’s national average of $11,841. Another Chicago school district, Roundout District 72, finds itself able to spend $28,639 on each of its students.

With the passage of No Child Left Behind almost two decades ago, the federal government began to drive major changes in how public education would be delivered and increased the level of “accountability” that would be imposed on local schools. Governors and state legislators have led efforts to seize greater control for public education from local school officials. But greater operational control has not been matched with greater fiscal responsibility. Rather, for many districts local taxpayers are left with a greater share of a shrinking school budget. And spending less matters.

Earlier this year, NPQ reported on another recent study, “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” by C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker C. Johnson, and Claudia Persico.

Money alone may not lift educational outcomes to desired levels, but our findings confirm that the provision of adequate funding may be critical. Importantly, we also find that how the money is spent matters…a 25 percent increase in per-student spending over the course of a student’s school-age years could eliminate the gaps in income and years of education between children from low-income families and those making at least twice the poverty line.

Here’s a first-week-of-school quiz for federal and state educational policy makers: Do current federal and state policies fund local schools at a proper level? If not, how can funding grow? Do we fund each school and every student equally? If not, how will we ensure that we do? If your answer is to continue dumping the school funding burden on local shoulders, you will get an “F” on this test.—Martin Levine