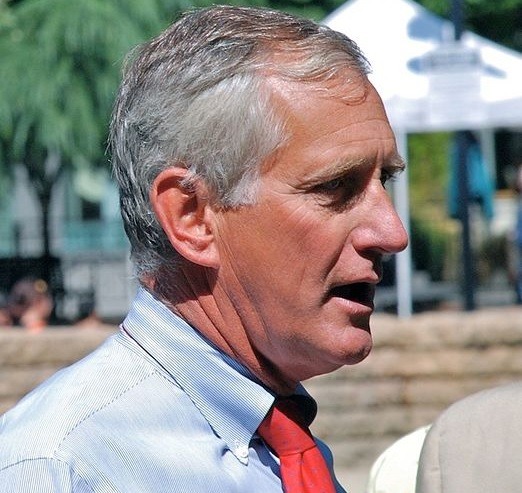

In announcing that he had changed his plan to run for a second term as mayor of Portland, Oregon, Charlie Hales shocked the community. Mayor Hales cited as a reason for his decision the need to dedicate all his energies as incumbent mayor to the problem of affordable housing:

“Hales said he’ll focus on issues during the 14 months left in his term, including long-term planning, curbing gang violence and lobbying the 2016 Legislature to lift a ban on a type of zoning that encourages affordable housing. ‘Trying to keep housing affordable in a city this size in a real estate market this hot, that’s a huge challenge,’ Hales said. ‘These are big deal issues and I just relish the opportunity to work on them and not have to think about campaigning.’”

One advocate describes the past month as “big changes—and fast,” as the city council adopted a moratorium on “no cause” evictions and the mayor sought support for converting public buildings into emergency shelters for the homeless. Here’s how the mayor summarized the “emergency” response:

“We’ve got some good things starting. We’ve got $66.7 million on the table this week to allocate for affordable housing. We’ve got efforts underway at both the county and city to expand shelter capacity and outreach to people on the streets. We’ve got all kinds of partners to count on that we can help if we’re not distracted by a political campaign.”

At the time of the declaration of the “homeless emergency,” Nonprofit Quarterly featured a story that contrasted Hales’s “emergency” declaration and a long-term planning process adopted in Portland, Maine. Mayor Hales’s latest moves seem like an evolution of that strategy. How these goals square with the earlier “homeless emergency” isn’t exactly clear, but the shift from a service strategy (shelters) to an affordable housing strategy is probably a good idea. Just amping up shelters to get the visible homeless off the streets ignores the deeper issue of affordable housing.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“Homeless emergencies” have become a fad in the West, with action expected in Eugene, Oregon, shortly. Around the same time as Mayor Hales’s September 23rd emergency declaration, the cities of Los Angeles and Honolulu also declared “homeless emergencies.” Like Portland, each of these cities’ emergencies seems to be evolving also. In Los Angeles, county officials have just announced a $100 million fund to support affordable housing in Los Angeles County:

“The county action comes as Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that the city will consider imposing new fees on developers to subsidize affordable housing within the city limits. Both the city and county are working on a larger strategy to address the area’s homeless population of 44,000. The supervisors did not say where the money would come from, but directed the county chief executive to come back with a plan as part of next year’s budget process.”

In contrast to Oregon, Los Angeles benefits from a California Supreme Court decision issued just this past June that opened the door for local inclusionary housing requirements. Rental housing developers in fast-growing states fear zoning rules that could require them to include affordable units along with “market rate” units in new developments. The California initiatives sound like the kind of plan that Mayor Hales might embrace in his remaining 14 months in office.

In Honolulu, by contrast, National Public Radio’s “Marketplace” reports that the city is cracking down on homeless encampments. That’s the trouble with a “homelessness emergency.” It feels a lot like temporary removal of homeless people from public view. Right after the Mayor’s announcement in Portland, there was the specter of “sweeps” of homeless encampments. Advocates are split on the “homeless emergency” approach. Some welcome the renewed attention to their cause. Shelter providers value recognition of their work, but they deplore police tactics to clear the camps. Other homeless advocates argue that systemic changes—more affordable housing linked to services—are required. This latter approach is the “housing first” model. Sensible public policy demands a balanced approach, as Rick Cohen points out in his NPQ newswire, “Stories of those Homeless Who Don’t Fit the ‘Housing First’ Model.”

Mayor Hales’s decisions to join the fight against Oregon’s 16-year-old inclusionary zoning requirements and to focus on long-term planning goals suggest he’s moved toward a systemic change model and away from the emergency approach. In these efforts, Mayor Hales will have the support of Oregon’s housing advocacy community. Unaddressed, so far, in any of these proposals is the development of a range of affordable housing that spans the situations of homeless people who need deep rental subsidies and linked services and those of working-class households that need rents at roughly 30 percent of household income.—Spencer Wells

Thanks to Rob Prasch of Network for Oregon Affordable Housing for his help in providing sources for this article.