December 28, 2017; Next City

A growing number of cities across the US are considering launching city-owned “public banks,” reports Deonna Anderson in Next City. Among these are Portland, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Oakland, California; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Washington, DC. Nationally, the Public Banking Institute, an advocacy nonprofit, has been supporting these and many other campaigns.

At the state level, Anderson notes that in New Jersey, the governor-elect “expressed interest in establishing a state public bank during his campaign.” Governor-Elect Phil Murphy’s endorsement of the concept of a public bank may be a watershed of sorts. Murphy spent 23 years at Goldman Sachs, so he knows a thing or two about finance.

Actually, Murphy’s rationale for supporting a public bank in New Jersey has a lot to do with what he learned on Wall Street. According to Katherine Landergan of Politico, on the campaign trail, Murphy noted that,

When New Jersey collects taxes or fees, it currently deposits those funds in private banks—spreading the state’s money across American and international institutions. Those banks, in turn, charge fees … and they use the capital from New Jersey’s deposits to provide loans or finance projects.

“They’re not being obligated to come back and do anything in New Jersey, and they don’t.”

Murphy’s vision of a public bank, Landergan explains, would enable the state to “bring some of those deposits home, and use the money to finance three lines of business: student loans, small business loans, and small-scale infrastructure projects for cities and towns.” Murphy’s campaign estimated that the average student borrowing from a public bank might save $8,000 overall due to better refinancing options and lower interest rates made possible by the fact that a public bank, while still needing to earn money, is, unlike private banks, not obliged to maximize profit.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In Portland, Oregon, according to Anderson, moving money off of Wall Street and back into the city is also a key objective. As Anderson explains, support for the public banking idea in Portland has grown in parallel with Portland City Council displeasure at the financial industry. Anderson notes that Portland’s City Council voted “in April to stop investing city money in all corporations. Portland is also one of numerous US cities that decided to stop banking with Wells Fargo, after the bank’s fraudulent accounts scandal made headlines.”

David E. Delk of the Portland Public Banking Alliance, a local advocacy nonprofit, says a “public bank would give the city more control over its finances, and allow it to avoid using local resources to assist the ‘too big to fail’ banks that caused the great recession.” It’s worth noting that the City of Portland has paid nearly $1.6 billion in interest to banks since 2005. Recycling that interest through a public bank could improve city finances, as well as augment the city’s ability to finance and thereby achieve public infrastructure objectives.

“My hope is that a public bank would be a profit-making institution except the profit would be for public purposes,” Delk says. “The possibilities are limited really only by our imagination because the needs are so great.” Anderson adds that, “The Alliance imagines that the public bank would also partner with local credit unions and community development financial institutions (CDFIs) to provide loans to students for college.” On City Council, Commissioner Chloe Eudaly has been a visible advocate for the concept.

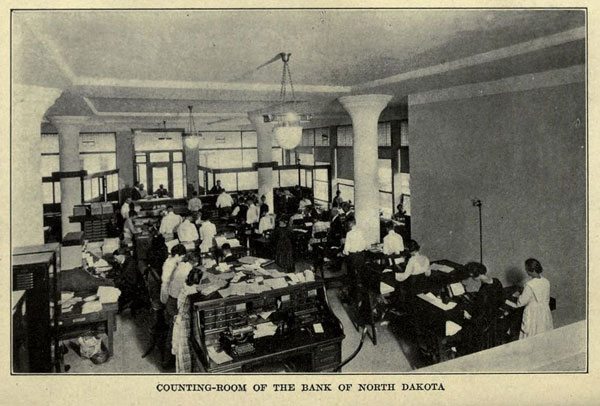

This may all seem pie-in-the-sky, except that there actually is a living, breathing, and highly successful example of the concept—namely, the nearly century-old Bank of North Dakota. As Oscar Perry Abello wrote in Next City last May, the North Dakota bank opened in 1919 “with $2 million in capital ($28 million in today’s dollars accounting for inflation).” Today, the bank has $7.2 billion in assets. Abello adds that the bank “functions largely as a ‘banker’s bank,’ mostly making low-interest loans alongside or directly to community banks and credit unions around the state.” The presence of the public bank, Abello writes, is “a big reason why North Dakota has more banks and credit unions per capita than any other state.”

A 2016 report by Karl Beitel of the Roosevelt Institute likewise argues that municipal banks, while not a cure-all, “can…combined with well-crafted local tax and land use policies…offer a powerful tool for supporting investments in affordable housing, providing funds for land trusts and cooperative rental housing, and nurturing local business and worker cooperatives.”

Of course, the politics of setting up a public bank will not be easy. It is notable that the establishment of North Dakota’s public bank a century ago relied on a third party, known as the Nonpartisan League, winning a statewide election in 1918 against both Republican and Democratic Party opposition. Nonetheless, as frustration with the financial services industry mounts, the public banking idea is gaining increasingly widespread support.—Steve Dubb