This article accompanies the recent NPQ webinar, “Compensation Equity: Operationalizing Justice Values in Nonprofit Pay Structures,” presented by the authors. The recording of the webinar is available to NPQ’s Leading Edge members or for individual purchase.

The social sector has traditionally given feverish attention to executive compensation, often with narratives of martyrdom when it’s viewed as chronically low or “gotcha” when it’s viewed as unethically high. But these discussions typically ignore and even distract from more fundamental assumptions that undergird compensation philosophies.

Nonprofits differ from for-profit businesses or governments; they have different purposes, different revenue sources, and embody different cultural values.

Today more nonprofits, especially those dedicated to racial and economic justice, are confronting how their current approaches to pay and compensation position them inside the very capitalist systems they so often challenge. They are asking: “Is how we pay our own workers in alignment with our proclaimed values and external-facing work?” For many, the short answer is “no.”

As we bring greater focus to common nonprofit compensation systems, we can no longer ignore how nonprofits often perpetuate inequities among their staff that they seek to eliminate in the world.

Interrogating Traditional Compensation Assumptions

Influenced by Milton Friedman’s 1970 call for businesses to maximize shareholder values over all others and the rise of neoliberalism that Friedman’s work helped inspire, there has been a push to run government services and nonprofit organizations more like businesses: efficiently and “at a profit.”

Yet nonprofits differ from for-profit businesses or governments; they have different purposes, different revenue sources, and embody different cultural values. A nonprofit’s purpose, broadly speaking, is to benefit the public. It likely has a mixed revenue model that might include private donations, grants, and earned revenue. Similarly, its dominant work culture is likely collaborative, although some functions may be more competitive (fundraising), creative (programming), and controlling (finance and operations). It stands to reason that nonprofits are not simply trying to minimize their costs and maximize their output.

Nevertheless, nonprofits still operate within neoliberal capitalism, entrenched into the country’s legal fiber for over a half-century. As employers, nonprofits—or the nonprofit industrial complex as it’s been dubbed—account for more than 12 million jobs in the United States. This includes social justice organizations. Unfortunately, nonprofits have not been able to protect their employees from rising living costs, deepening inequality, or exacerbating racial and gender wealth gaps, even when reducing the income gap has been shown to dramatically reduce the racial wealth gap. Just as the broken social contract was exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic and racial justice uprisings, inequities in employment contracts have also been laid bare.

We did not fully predict the degree of staff conflict we found at some of the most progressive nonprofits about divesting from unfair pay structures.

Nonprofits that advocate for social justice and center their work on the voices, lives, and leadership of those most impacted by social injustice have a particular opportunity—perhaps even a moral imperative—to address their own employment inequities. Transforming nonprofit compensation systems can help hold nonprofits accountable.

The Complex Tensions of Nonprofit Pay Equity

Co-author Mala Nagarajan has worked on pay equity with social justice organizations for seven years. Over time, she’s evolved her approach. Recently, as Borealis Philanthropy fellows, we launched pay equity pilots with a number of progressive nonprofits. The pilot design included small group dialogues for participants to address their personal feelings about money, give feedback about their organization’s current pay scale, and identify their highest priority values for a new compensation system.

These pilots unearthed the difficulties in moving from a market-based model to a values-aligned one. We anticipated complicated feelings about money based on intersecting identities—and we expected more critical views about traditional pay scales that operate from harmful market-based assumptions. Still, we did not fully predict the degree of staff conflict we found at some of the most progressive nonprofits about divesting from unfair pay structures. Objections came not just from higher paid White staff but also among many staff of color across class backgrounds.

Tensions were palpable. On one side are workers who were advocating to be paid more for a range of important reasons. The participants quoted below, edited slightly for anonymity, expressed these concerns:

- “I moved to this job and already took a huge pay cut because I love this organization, and I need my pay to be compared to where I left rather than where I am now, in case I don’t stay here forever.”

- “My counterparts at other national institutions are making up to two-to-three times as much as I am making. As a BIPOC executive director, I need to be paid at least as much as my counterparts.”

- “Correcting pay for historical injustice and income gaps is critical, and does that mean that my college and graduate degrees are now worthless?”

- “How do older workers closer to retirement age deal with the rules of the game being changed at this late stage of our careers? Some of us are playing catch-up on contributing to our retirement for all the years we did not have access to a retirement account.”

- “Don’t we need to be tackling this at a systemic level, asking the one percent to pay their fair share? It’s just wrong to ask nonprofit staff, who already make less than their for-profit and government counterparts, to reduce their salary to support reparative justice.”

On the other side are workers who prioritized the constituencies they served over their own pay, livelihood, and sometimes survival. This was not unexpected at the progressive nonprofits we work with; they were advocating to be paid less. They wanted less differentiation between levels in the organization, as noted below:

- “Our organization’s resources should be going to the individuals, communities, and organizations we’re supporting, not into our pay.”

- “Our pay should not be significantly different from the salaries of the organizations or the community members we’re working with, at least for solidarity’s sake.”

- “Supervisors should not be paid more than their direct reports because managerial labor should not be valued more than emotional, physical, or relational labor, especially in front-line positions.”

Often tensions revealed deep social conditioning, survival hardships within capitalism, and personal resentments for racial and class justice in practice, not just theory. These tangles remind us that as pay equity consultants and as social justice nonprofit leaders, we must understand the social psychology related to money to truly realize pay equity and reverse the racial and gender wealth gaps.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Social Psychology of Pay

The social psychology of pay is a major driver behind people’s feelings about their own pay and peer compensation. People make meaning of their compensation in relation to their past, their peers and colleagues, their families and communities, and their social positions. One of the most important lessons from our work is that our sense of equitable compensation is highly context-dependent. That said, three trends offer cause for optimism about a growing commitment to pay equity.

First, a paradigm shift at work is underway, which includes more open discussion about compensation. Some people are surprised to learn that it is not illegal to discuss pay at work. In fact, there are federal protections against employer discrimination and retaliation for doing so. The fact is that long-held and deeply entrenched cultural norms have pressured employees against talking about pay. These norms are gradually eroding among new generations of workers. As of 2021, a poll found that the majority of Americans (55 percent) would prefer to let their coworkers know their pay, with a staggering two-thirds of 25-to-34-year-olds saying they would prefer this.

People make meaning of their compensation in relation to their past, their peers and colleagues, their families and communities, and their social positions.Second, there is growing awareness about market-based conditioning and a willingness to put resources toward values. Nonprofit workers are not shy about voicing their criticisms of the market-based compensation status quo and are making active connections to what the economist Robert Reich has called supercapitalism, a form of market domination which operates, he argues, at odds with democratic values. Nonprofit staff extend this analysis to the controlling behavior of funders and philanthropists as well. While more nonprofit workers have turned to unions to change these conditions, others are directly demanding changes within their organizations.

Third, there is an increasing uptake in newer practices around CEO pay ratios. Many of us are appropriately outraged by grotesquely large CEO salaries, particularly when compared to many frontline workers who make a fraction as much and on whose labor companies depend. The organizations that we work with have been willing to adopt a 2.5:1 ratio or less between the highest-paid and lowest-paid staff members.

Shifting to Restorative Compensation

More and more, nonprofits need to reimagine and restructure their compensation models. In our work, we use the term “restorative compensation,” a system that restores labor that is undervalued and unseen and invites people to treat the employer-employee relationship as a consensual exchange, not a contractual exchange or extractive commodity. Along a labor continuum, this moves compensation systems from a dominance-centered to a liberatory-centered frame.

A good place to begin this change process is by creating a well-articulated employer philosophy that makes explicit how the nonprofit wants to relate to its employees. Not only can it articulate the organization’s values-aligned aspirations as an employer, but it also needs to acknowledge, elucidate, and advance how the organization will address its constraints. Spelling out the unique constraints nonprofits face is critical, especially given the inherent tensions of the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world in which we operate.

From there, a restorative compensation model requires reengineering compensation systems. Here are some key elements:

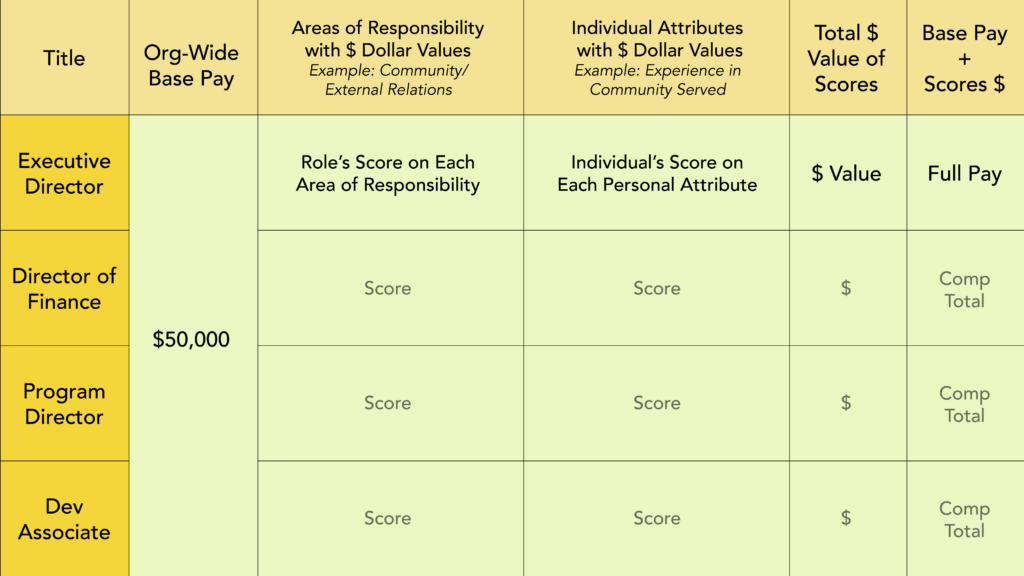

- Start all staff with the same base salary (that is, base pay/wage). Starting everyone from the entry-level person to the executive director with the same pay embodies the idea that we all start as equals. Base pay encapsulates shared responsibilities, shared commitment to the organization, and the unique responsibilities one holds in a position that are not reflected in the organization’s Areas of Responsibilities Matrix (see example below). Hierarchy is established not through title, but through transparent areas of responsibility.

- Lift up, value, and compensate monetarily a set of organization-informed areas of responsibility (AORs). This is the process of visibilizing all work, not just the standard qualifications, contributions, and working conditions. Physical and emotional labor, exposure to liability, and exposure to harm are just a few examples of areas of responsibility that can be lifted.

As Marilyn Waring pointed out in Counting for Nothing, the economic system does not count unpaid labor or the things that people most value. We know that dirty work, women’s work, Black labor, and work done by marginalized communities is minimized, devalued, and invisibilized. In restorative compensation, we lift up what labor the work requires—for example, recognizing that people on the front lines perform emotional labor.

In traditional compensation systems, what gets valued, how much, and why remains opaque. In a restorative system, we conduct a job analysis assessment using an areas-of-responsibility lens to provide transparency and recognition to what people are holding in their roles, understand how each position engages with specific areas of responsibility, and begin to understand how positions are integrated and interdependent.

- Control the difference between the lowest-paid and highest-paid worker. Organizations are encouraged to work toward the practice of having the highest-paid full-time equivalent (FTE) worker make no more than two-to-three times the lowest paid (FTE) worker. When considering what ratio to set as the target, we advise organizations to use the number of staff, their budget size, and the organization’s stage of development to target a ratio that feels fair. Small organizations often have ratios of less than 2:1. In larger-staffed organizations, it’s common to see a 4:1 ratio. A fast-growing organization may need to temporarily go over its ratio for key positions. Before organizations raise the highest salary in the organization beyond a 3:1 ratio, we recommend making sure all workers are earning enough to thrive and enough to make up for and transcend any benefits cliff they may experience.

- Set equal-sized ranges for each band (that is, job group). Market-centered scales are designed to create more narrow bands for lower-leveled positions (for example, $40,000 to $45,000 for associates) and higher, broader salary bands for higher-leveled positions (for example, $90,000 to $120,000 for directors). This practice perpetuates similar patterns to percentage-based increases, rewarding higher increases to those already at the highest levels of compensation. In a restorative system, all job bands are of equal size or replaced by the areas of responsibility calculations.

- Invite staff to redistribute. Restorative compensation allows privileged colleagues to voluntarily take less and colleagues who have been more disadvantaged in their lives to earn more. Co-author Mala Nagarajan has prototyped such a redistribution process—the Reparative Distribution Factor™ (RDF). We consider this emergent practice as an example of interpersonal and community reparations with a little “r.”

Explanatory Note: The graphic above is a high-level representation of the compensation model described. Note the shared base pay of all positions, the scoring of every position on multiple organizationally identified factors, and the final compensation for each position at the far right. All positions are scored on all factors to recognize and demonstrate the interdependence of people’s work, their comparative qualifications (experience), and the working conditions (high risk/vulnerability) the positions are exposed to.

Conclusion

Moving away from traditional, market-based compensation models is a concrete way for nonprofits committed to racial and economic justice to align their values with their practices. But the work outlined above is not transactional; it is a mistake for leaders to view it as a single, human-resources system change. Rather, this is deep organizational development work. Fundamentally, the work invites people across the entire staff into a profound grappling with their personal beliefs about money and their assumptions and expectations about how to survive and thrive in a capitalist system. As such, its success requires broad staff participation, shared decision-making, and consent-based transformation.

Thank you to the generous support of the Borealis Philanthropy REACH program for their multiyear grant that has supported making the learnings from this work more available to the field.