April 12, 2019; Rewire.News

When told, the stories are almost always heartbreakingly similar: A black woman encounters substandard maternal care, resulting in a set of likely avoidable tragic consequences if only someone along the way had just given a damn.

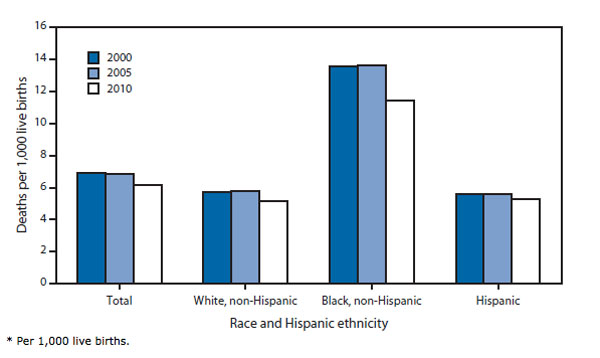

It’s not as if racial disparities in infant mortality are new. Back in 1850, when the US began keeping statistics about infant mortality, the black infant mortality rate was 340 per 1,000 while the white infant mortality rate was 217 per 1,000. Fortunately, overall infant mortality rates have plummeted for both blacks and whites. But the ratio of black infant mortality to white infant mortality is greater today than in 1850.

In 2018, the New York Times reported black infants are more than twice as likely to die as white infants. The Times adds: “Education and income offer little protection. In fact, a black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with less than an eighth-grade education.”

Not just the babies are at risk. According to statistics collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from 2011–2014, black women died a rate over three times as high as white women during childbirth (40.0 deaths per 100,000 live births versus 12.4 deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively).

The crisis of black maternal and infant mortality is a big factor in the country’s overall decline of our global ranking in infant mortality; the US was 12th among developed nations in 1960 and now ranks 32nd out of the 35 wealthiest nations. Translation? Iran and Libya have lower infant mortality rates than we do.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Why? Per the New York Times:

The reasons for the black-white divide in both infant and maternal mortality have been debated by researchers and doctors for more than two decades. But recently there has been growing acceptance of what has largely been, for the medical establishment, a shocking idea: For black women in America, an inescapable atmosphere of societal and systemic racism can create a kind of toxic physiological stress, resulting in conditions—including hypertension and pre-eclampsia—that lead directly to higher rates of infant and maternal death. And that societal racism is further expressed in a pervasive, longstanding racial bias in health care—including the dismissal of legitimate concerns and symptoms—that can help explain poor birth outcomes even in the case of black women with the most advantages.

And now, finally, lawmakers are beginning to react, with a blizzard of some 80 bills across the country addressing black maternal and infant mortality. Three states—California, Illinois, and Texas—are looking at racial bias in health care, ten more states have proposed bills expanding access to doula care (a doula, as NPQ has previously described, is a person trained to provide support to a mother before, during and after childbirth), and 19 more states are establishing task forces to investigate.

But if the increasingly widely held belief that race-based stress is at least partly to blame is true, there remains a larger agenda to pursue that involves far more than the medical community.

Raena Granberry, an activist with firsthand experience in the maternal health care divide and who now works with Black Women for Wellness, says, “What we have been doing for decades is putting all of the responsibility on black mothers. You need to be healthier, you need to try to reduce your stress, you need to do this and that—and obviously the outcomes have not changed. It’s because nothing that we can do as black women can change what our experiences are as a black woman. I can’t change how people are going to treat me and what the world is like for me.”

If you add in the systemic influences of Medicaid on prenatal health (half of all births are financed by Medicaid but many providers don’t accept it, complicating access to care), and hospital quality (low quality hospitals account for half the racial disparity in maternal illness) the complex web of barriers to access and racially motivated disparities in care even with access results in a lose-lose assessment where it is too easy to point to unhealthy lifestyles and ignore the larger issues of societal toxicity.—Eric Fullilove