July 29, 2020; Vox and Washington Post

Change is hard. It seems particularly difficult for those who have held positions of leadership for long periods of time.

Education—what is taught and how we teach it—provides one example of this. While school leadership is constantly revising curricula, courses, and schedules, the content, especially in history and literature, often is only adjusted incrementally. But change is in the air, and that push for change is coming from our youth, who are asking questions about what they are being taught.

Students are noticing that their history courses often downplay the role of white supremacism in the nation’s history and that much of their reading and literature focuses on the white US experience while giving less attention to stories written by Americans of color. One of the drivers of this gap between content delivered and student demand has to do with the fact that teachers (and administrators) are much less diverse than their students. As the National Center on Teacher Quality has documented, about four in five teachers are white, even as students of color form the majority of students enrolled at public schools nationwide.

One effort to change the curriculum is being promoted by a group called Diversify Our Narrative, a campaign spearheaded by California college students. The group aims to alter school curricula to ensure that public school students receive education in the classroom about race, racism, and anti-racism. To date, the group has trained 1,700 students in 200 school districts to be community organizers. Students who join are given tools and resources like “email templates and social media tips to start a local petition targeting [a] community and school board,” explains Terry Nguyen in Vox.

As Nguyen details, issues of systemic racism present in our society manifest in our school systems—in their structure and funding, as well as in their curricula. What is taught says much about how this nation views itself. The adoption of Common Core standards in 2010, for example, relied heavily on the Western canon—works of mostly white authors—for grades 6-12, and the books included often fail to speak to the daily concerns of the students who attend the schools. Indeed, the gulf between what students are taught and what is likely to engage those students to learn can be large.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

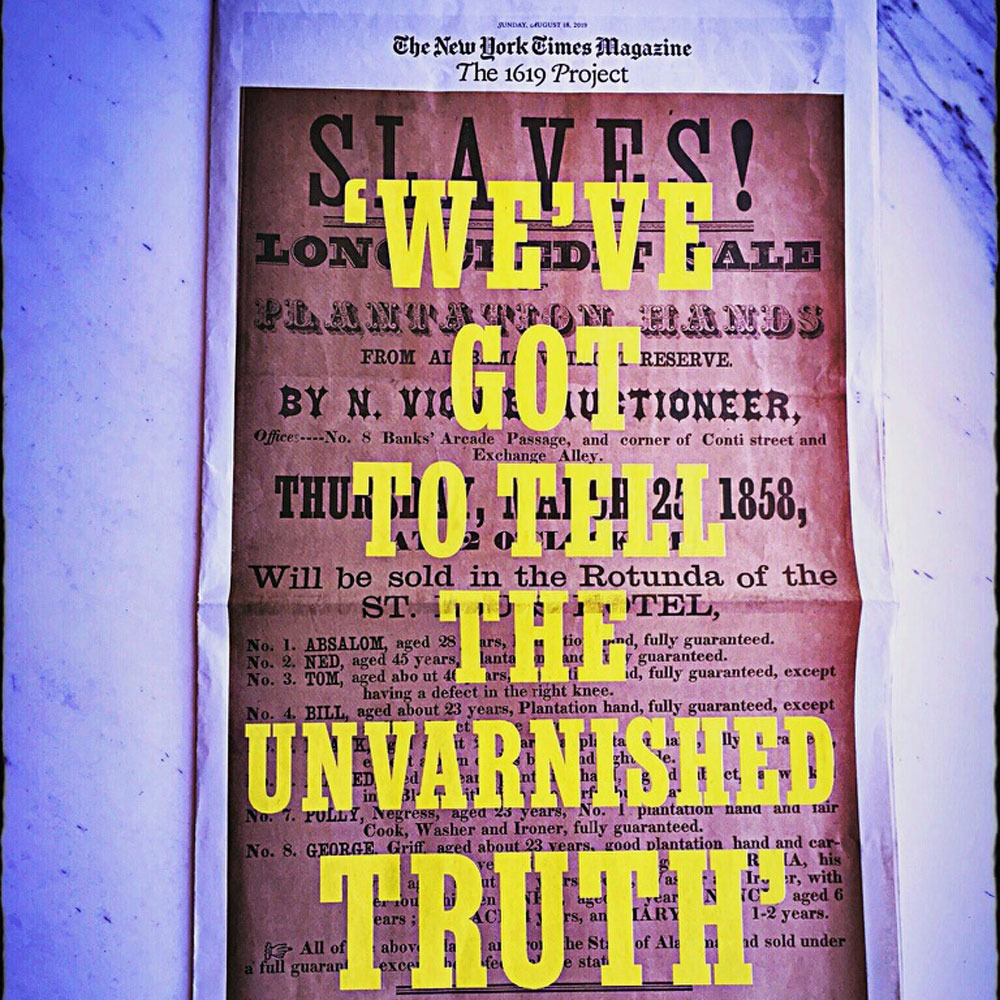

Even as youth take a leadership role in changing narratives, resistance to change remains fierce. In Washington, DC, for example, Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) introduced a bill to withhold federal funds from schools that use The 1619 Project in the classroom. The 1619 Project is a series of essays, poetry and fiction published in the New York Times that takes on the way the enslavement of Black people is portrayed in US history. Nikole Hannah-Jones, the project’s creator, won a Pulitzer Prize for an essay that helped launched that project, and the series has been adapted into lesson plans that several major school districts plan to use. It might be worth noting, too, that Title I schools—that is, schools with low-income students and often heavily students of color—are frequently the largest public-school recipients of federal funds and thus would be the most directly affected.

Cotton’s bill would prohibit elementary and secondary schools from using federal funds to teach based on the publication at all. “The entire premise…is that America is at root, a systemically racist country to the core and irredeemable. I reject that root and branch,” Cotton tells the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Of course, Hannah-Jones disagrees. In an interview with WBUR’s Here & Now, she asserts her project seeks to counter a history that uncritically glorifies the country and that instead provides students with a more honest and comprehensive understanding of the nation’s history, warts and all.

“The way that history is taught in American schools is highly politicized and it really has a nationalistic agenda,” she said. “What that has meant is that it has necessarily downplayed the role of slavery.”

Meanwhile, youth are not waiting for debates in Washington to resolve in order to speak up in their own districts. One such voice is that of Bethlehem Wolde, a senior at Baltimore County’s Catonsville High School and a member of the Black Student Union. “I have a younger sister and younger cousins,” she says. “I don’t want them to experience microaggressions or be the only Black student in a high-level class. I want them to be in a better learning environment, to learn more about Black history, and be aware of systemic disparities.” —Carole Levine