Most people in the United States who have health insurance obtain it through their employers. But what happens when the cost of this insurance increases? A study from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has some answers.

The study, Who Pays for Rising Health Care Prices? Evidence from Hospital Mergers, was authored by Zarek Brot-Goldberg, a public policy professor at the University of Chicago, along with five economists from the US Department of the Treasury, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and top US universities. The authors found that between 2007 and 2014 a 10-percentage-point rise in the cost of health spending (above overall inflation) led to an unemployment rate that was 0.86 percentage points higher than baseline.

Over the past decade, insurance premiums have grown by 47 percent—outpacing inflation by 17 percentage points.

While this may sound modest, the effect was that 1.44 million people earning between $20,000 and $100,000 lost their jobs—individuals who otherwise would have remained employed.

There were, of course, many other impacts. Worker incomes were 2.7 percent lower. Federal tax revenues were 3.4 percent lower. And health impacts were significant, too: an estimated 10,000 additional deaths due to what has been called “deaths of despair”—namely, drug overdoses and suicides.

What causes these outcomes? The problems of the US health system are many, but as Brot-Goldberg and his coauthors illustrate, a dysfunctional private health insurance system and increasing hospital consolidation are clearly among them.

Rising Healthcare Costs

The cost of healthcare in the United States has risen sharply over the past two decades. Healthcare spending has nearly doubled from $2.5 trillion in 2000 to $4.5 trillion in 2023, equating to a per capita cost of over $13,000.

Over the past decade, insurance premiums have grown by 47 percent—outpacing inflation by 17 percentage points. For a family of four, the average yearly health insurance premium was $23,968 in 2023—roughly the price of a new Toyota Corolla.

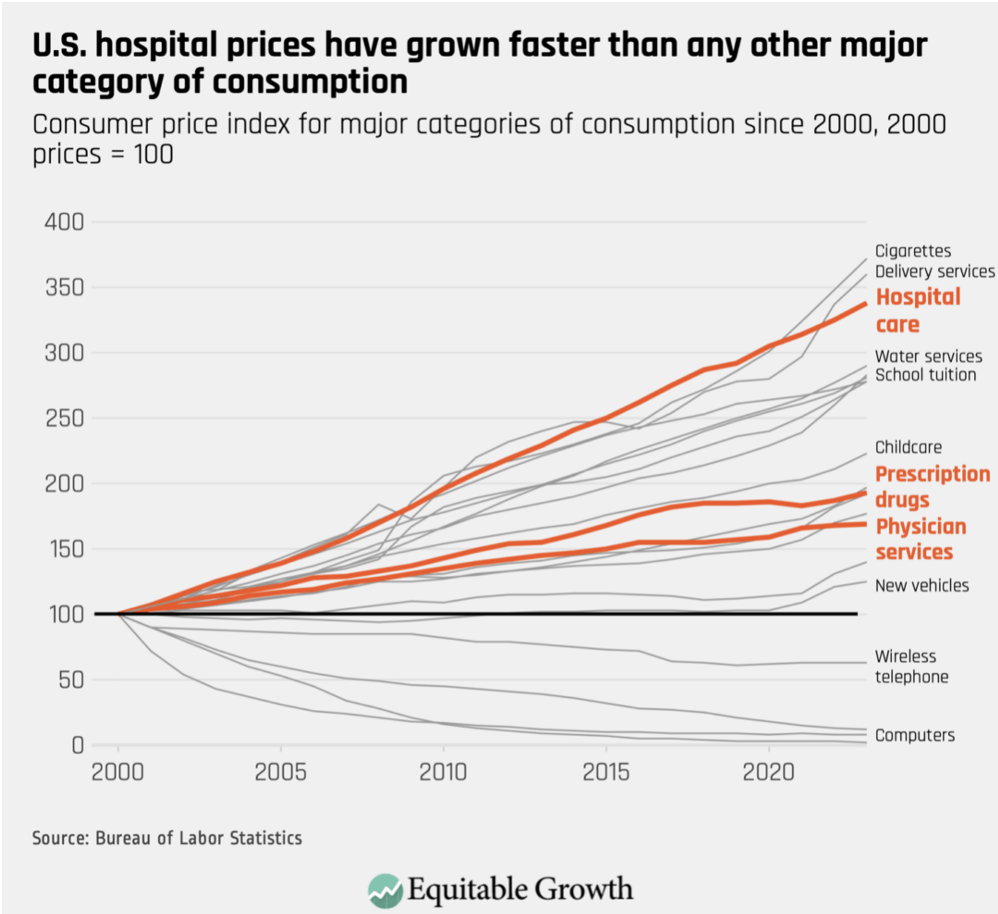

As can be seen from the chart below, hospital care prices have outpaced overall inflation since 2000:

In some sectors, rising prices may reflect improvements to the quality of service. However, according to Brot-Goldberg et al., in healthcare, “industry tactics like mergers and acquisitions, surprise medical billing, upcoding, and patent hopping” are the primary cost drivers.

The Tug of War Between Insurers and Hospitals

Underlying these tactics, Zarek Brot-Goldberg and his colleagues demonstrate, is an internal tug of war between insurers and hospitals that is driving up health insurance costs.

Insurance costs are “the outcome of negotiations between the hospital and insurer,” Brot-Goldberg told NPQ. “Generally, people are covered by some sort of health insurance, usually by a private insurer. The hospital and the insurer have agreed upon a price the insurer will pay the hospital in the case that a person goes there.”

“Now the insurer, of course, wants a lower price and the hospital wants a higher price.” Brot-Goldberg said. “The thing that allows the hospital to charge a high price is the fact that people have a strong preference for [care in] hospitals.”

An internal tug of war between insurers and hospitals is driving up health insurance costs.

As the study points out, hospitals wield significant bargaining power, especially when they are the preferred or sole providers in a region. If an insurer refuses to agree to higher prices, the hospital may decline to be included in the insurer’s network. This can deter customers from choosing that insurer if their preferred hospital isn’t covered.

Brot-Goldberg described another scenario to NPQ: “Now, imagine there [are] two hospitals in an area….If one of the hospitals tries to hold out for a very high price, the insurer can say, ‘Look, I don’t care. I’ll just send all my patients to the other hospital,’ so that competition keeps prices low.”

However, if the two hospitals merge, a hospital can negotiate a higher price from insurers because there’s less competition.

The Impact of Hospital Mergers

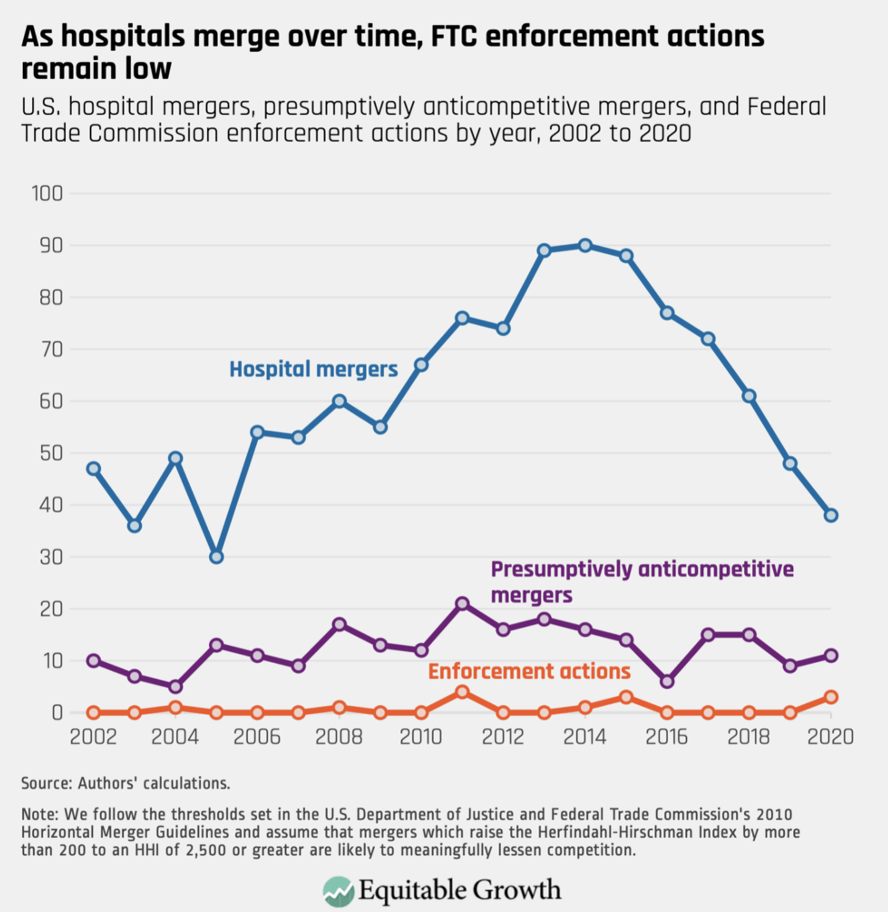

Hospital mergers are increasingly common. Between 2000 and 2020, Brot-Goldberg and his colleagues report more than 1,000 hospital mergers among the 5,000 hospitals total nationwide.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

According to the study, each hospital merger, on average, resulted in 39 job losses, approximately $6 million in forgone wages, and a $1.3 million reduction in federal income tax revenue.

For mergers that raised prices by 5 percent or more, the effects were more pronounced, with an estimated 203 job losses, about $32 million in forgone wages, and a $6.8 million reduction in federal income tax revenue.

Mergers and Inadequate Regulation

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) oversee and regulate mergers to prevent anti-competitive practices. They use the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which examines the number, relative size, and distribution of competitors in a market, to determine how competitive a market is pre- and post-merger.

According to DOJ and FTC guidelines, “mergers resulting in highly concentrated markets that involve an increase in the HHI of more than 200 points will be presumed to be likely to enhance market power,” meaning these mergers increase prices.

According to Brot-Goldberg and his coauthors, 20 percent of the more than 1,000 mergers completed between 2000 and 2010 increased prices. However, only 13 mergers total were determined to be unethical, demonstrating a lack of real oversight to prevent increasing costs for consumers.

More Than Money—Job Loss, Overdoses, and Suicide

In a toxic capitalist cycle, workers bear the brunt of the battle between hospitals and insurers.

If a family health insurance plan costs nearly $24,000, how can employers afford to provide it? Often, they offset their insurance costs by paying their workers less—or cutting jobs altogether, exacerbating income inequality and economic instability. The US Department of Labor forecasts that more than 600,000 jobs that pay between $40,000 to $100,000 yearly will be lost.

The financial costs are bad enough. But one of the most damning findings of the study concerned the relationship between rising health costs, lower employment levels, and resultant harm to individual health. Of course, job loss can affect a person on both a financial and an emotional level. Depending on the circumstances, one can feel betrayed by their former employer or blame oneself for perceived shortcomings or mistakes. There can be a sense of powerlessness over the direction of one’s life.

In a toxic capitalist cycle, workers bear the brunt of the battle between hospitals and insurers.

The study found that a one-percent increase in healthcare prices led to approximately one additional death from suicide or overdose per 100,000 people or a 2.7 percent increase over the baseline rate. This implies that approximately one in 140 individuals who become fully separated from the labor market after healthcare prices increase die from a suicide or drug overdose.

This finding is not altogether surprising given findings of similar effects from job loss due to US auto plant closures in the 2000s. In that case, a study published in 2019 in JAMA Internal Medicine found that five years after a plant closure, mortality rates had increased by 8.6 opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 individuals.

A Path Forward

At present, over half of Americans have private insurance through their employer. Yet, as Brot-Goldberg’s team shows, such health insurance can harm both local economies and the people who live in them.

Healthcare spending represents over one-sixth of the US economy (17.3 percent of gross domestic product)—but the country remains politically divided on how to address it. A 2023 Gallup poll found that 57 percent of respondents favored the federal government guaranteeing access to healthcare versus 40 who opposed it, but the same poll found that 53 percent favored a private insurance system, while 43 percent favored government-run insurance.

A single-payer, universal healthcare plan—that is, a government-run insurance plan—would resolve many of the employment and health problems that the authors of the study document, but significant political obstacles remain.

The authors of the NBER study hope their research motivates future analysis to address rising healthcare costs and challenge hospital mergers that exacerbate income inequality. The cost of inaction could be high.

“In the absence of concrete steps to address health care price growth,” the study authors warn, “rising health spending will raise labor costs and reduce business dynamism outside the health sector, put pressure on the federal budget, and exacerbate income inequality.”