June 3, 2015; Associations Now

Can there ever be too many wealthy financial professionals around the nonprofit board table? This is the question that Garry W. Jenkins, the John C. Elam/Vorys Sater Professor of Law, director and co-founder of the Program on Law and Leadership, and associate dean for academic affairs at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, raises in the Summer 2015 issue of the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

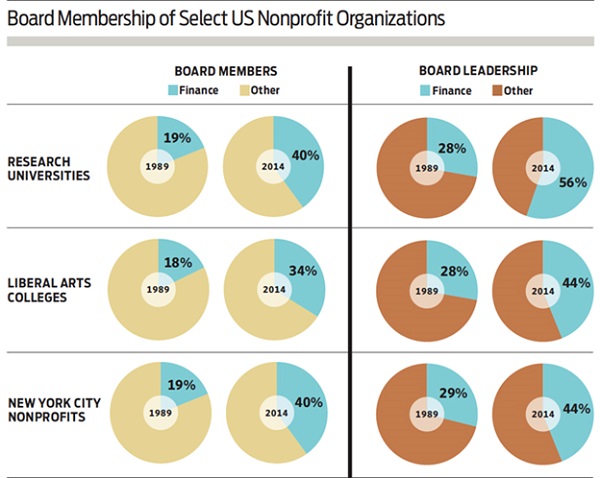

The data he and his research associates developed in a study of research universities, liberal arts colleges and New York City nonprofit organizations found that that between 1989 and 2014 the share of nonprofit board seats filled by financial professionals grew dramatically.

This change in overall board composition was also reflected in a growing proportion of board leadership being drawn from this one sector. For research universities, 56 percent of leadership positions were filled by financial professionals in 2013; for liberal arts colleges and NYC nonprofits, this number was 44 percent.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This is particularly striking as the financial services industry employs just six percent of the private non-farm workforce.

Professor Jenkins recognizes that there is good reason for nonprofit boards to seek to add successful financiers to their ranks. He notes, “Today’s…superstar money managers certainly outstrip the earning power of most others. For example, in 2010, in total the top 25 hedge fund managers earned nearly four times as much as the 500 chief executive officers of the Standard and Poor’s 500 companies.” And they have been quite generous with their wealth: “Between 2003 and 2013, the percentage of the 50 largest US donors whose source of wealth was finance soared from 10 percent to 36 percent.”

So, is there anything to worry about? Professor Jenkins thinks there is. He attributes the growth of “practices such as data-driven decision-making, an emphasis on metrics, prioritizing impact and competition, managing with three- to five-year horizons and plans, and advocating executive-style leadership and compensation” in the nonprofit sector to the increasing influence of financial management professionals. He also notes that beyond these changes in the management styles of nonprofits, “the rise in the number of nonprofit directors with ties to finance may also contribute to deeper changes in the underlying institutional values and motivations, a trend that economic sociologists refer to as the financialization of the nonprofit sector” which shifts “board and management attention to debt service, incentivizing organizations to invest resources on activities that return higher profit margins to cover debt service, elevating the centrality and importance of financial managers in strategic planning and decision-making, and increasing the need for and power of senior staff well versed in complex financial instruments.”

Professor Jenkins sees one additional area of concern, a threat to board diversity and inclusiveness. Beyond leaving less room for board members with differing professional backgrounds, having a board with a large proportion of financial professionals will make it more likely that there will be fewer women and minorities at the table. According to the U.S. Equal Opportunity Commission, in 2012, women made up but just 17.8 percent of executive and senior level managers in positions in the “securities, commodity contracts, and other financial investments and related activities” category. When it comes to racial minorities, “the numbers in the finance category are similarly paltry, with blacks holding just 1.4 percent of executive positions and Hispanics holding only 2.3 percent.”

Are these “costs” outweighed by the benefits? With the amount of wealth being generated in the finance sector, this is a question nonprofit leaders should be consider carefully as they nominate their next slates of board members and officers.—Marty Levine