July 6, 2016; Christian Science Monitor

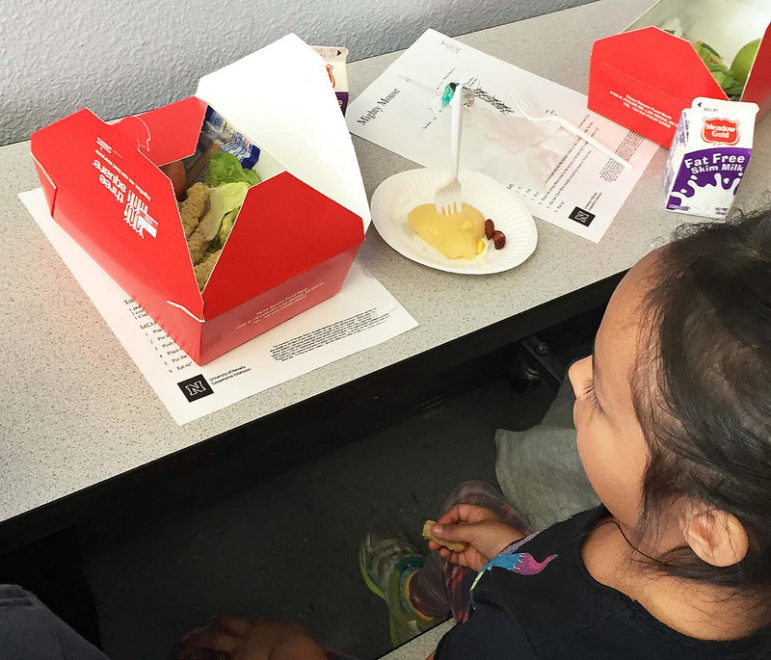

School may be out for summer, but the 22 million low-income children who receive free and reduced-price meals through the National School Lunch Program are temporarily out of a dependable resource for a nutritious meal. Though summer meals are provided through two federal programs, the National School Lunch Program Seamless Summer and the USDA Summer Food Service Program, according to the Food Research and Action Center, only one in six children actually access those programs. To help fill this gap in meals, organizations like Feeding America provide food to eligible kids in a variety of ways: free meals and snacks via existing community summer programs, backpack programs (in which bags of food are assembled at a food bank then distributed), and on-campus pantries created in partnership with schools that students and their families can access.

However, organizations that address hunger may have to work even harder to fill this hunger gap if the House Education and the Workforce Committee can pass H.R. 5003 through the House of Representatives. H.R. 5003 is the legislation that is proposed for reauthorization of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. This act was reauthorized with a stronger Summer Food Service Program in the Senate in January. But the House bill has the potential to negatively impact one of the programs in place to currently help low-income families: the Summer EBT program. Through this program, low-income families are provided with nutrition benefits though an Electronic Benefits Transfer card. In H.R. 5003, funding for this program is capped at $10 million per year—less than half the current level.

Several organizations have issues with other components of H.R. 5003 in addition to its potential negative impact on providing food during summer months. Hunger Free Colorado has expressed concern over the bill’s amendment to pilot block grants for school meal funding. Under the current legislation, school meals are reimbursed on a per-meal basis. Implementing a block grant would mean that each state is only given a set amount per year for school meal programs. Because legislation is in place for five years, block grants would prevent states from adjusting for local, regional, or national economic changes, which could mean more kids need the program.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Also, the American Heart Association opposes the bill based on its provision to allow states to determine what foods are deemed nutritious. The Association is working to raise awareness about the dangers of foods that contain high amounts of sodium, often found in processed foods. The Association is concerned that by allowing states to determine their own standards rather than adhere to federal nutrition guidelines, childhood nutrition will get worse.

And, California Food Policy Advocates are concerned about the bill’s provision to roll back universal school meal programs. Through this current provision, a school based in a community with an Identified Student Percentage of 40 percent or more offers free school breakfast and lunch to all students without having each student undergo an application process. Doing away with this program would mean schools located in high-poverty areas, which are already operating with a lack of resources, would have the burden of additional administrative costs.

The next step for H.R. 5003 is a full House vote.—Kelley Malcolm