Editors’ note: This piece is from Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine’s winter 2024 issue, “Health Justice in the Digital Age: Can We Harness AI for Good?”

In 2016, during the middle of her third year of law school, Lauren Blodgett received a diagnosis of a rare and severe autoimmune condition. Takayasu’s arteritis, also called pulseless disease, is a form of systemic inflammatory vasculitis that predominantly targets large and medium-sized arteries. The symptoms, which included flu-like effects, body lesions, and the loss of use of her left arm—flared up after Blodgett returned from human rights fieldwork in Morocco and Thailand. “I came back and spent eight months in and out of the hospital while balancing my caseload,” she said.1

It took eight arduous months to receive a diagnosis. During the process, Blodgett missed classes and work; but more important, the autoimmune condition subjected her body to ongoing assault and potentially irreversible damage. “They couldn’t figure out what was wrong with me,” she said. “And part of it is because they weren’t really looking at me holistically.”2 Blodgett was eventually selected for a Medical Grand Rounds session at Massachusetts General Hospital, in which a group of doctors formally convened to discuss her clinical case and ultimately provided her with a diagnosis and treatment plan. Although the diagnosis brought some relief, the prognosis was less favorable, requiring a lifetime of oral medications and injections to manage her condition.

Blodgett’s medical journey is far from unique. According to the National Institutes of Health, 25 million Americans endure mystery conditions that are difficult to diagnose and treat, while an additional 50 million people are affected by autoimmune diseases and syndromes (conditions without clear diagnoses or medical solutions)—making them the third most common disease category in the United States, behind only cancer and heart disease.3

While many practitioners have long observed the healing benefits of engaging with beauty, nature, and the arts, and scientists have been studying such effects for many decades, neuroaesthetics researchers are now zeroing in on the biological mechanisms behind the effects.

And these are just one large pool in the overall chronic illness category. Indeed, many Americans find themselves in similar situations to Blodgett’s, navigating the grueling and uncertain process of receiving a diagnosis for a mysterious disease and/or managing a chronic illness. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 129 million people live with at least one chronic condition.4 Americans, who make up 4 percent of the world population, consume around 8 percent of prescription medications globally;5 notwithstanding that relatively low number, the United States has the highest overall prescription drug spending in the world.6 For many, the situation is compounded by a lack of adequate insurance coverage,7 which leaves them struggling to afford both diagnostic tests and treatment. The high cost of medications, along with their side effects, adds to the already significant challenges people face in these circumstances.

In response to these hurdles, researchers and practitioners have been exploring alternative approaches, not only for managing chronic conditions but also for enhancing overall quality of life across diverse demographics. One promising thread that has been emerging is the field of neuroaesthetics, which examines the impact of art and beauty on the brain and wellbeing.

“Your Brain on Art”

For Blodgett, law school and work were already demanding, but her exposure to vicarious trauma added a new level of stress—she worked closely with immigrant clients who had endured significant violence. Many people in her position choose a self-sacrificing approach, often leading to burnout—but Blodgett chose to also maintain focus on her own health. She met with a holistic nutritionist and wellness coach in New York, under whose guidance she changed her diet, spent more time in nature, and started dancing. The results were astounding. “Now I’m fully in remission. I’m not on any medication, and I haven’t been for over a year,” Blodgett reported.8

Blodgett’s case highlights why neuroaesthetics has gained so much attention lately.9 While many practitioners have long observed the healing benefits of engaging with beauty, nature, and the arts, and scientists have been studying such effects for many decades,10 neuroaesthetics researchers are now zeroing in on the biological mechanisms behind the effects. As a result, a growing number of doctors in the United Kingdom and Canada have embraced prescribing music, dance, and other art activities—an approach supported by research showing that engaging in the arts helps with such ailments as Parkinson’s, dementia, heart disease, and obesity, and can alleviate depression and decrease chronic pain.11

The term neuroaesthetics, which describes the intersection of brain sciences and the arts, was coined in the late 1990s by Semir Zeki, prominent neuroscientist and professor at the University College of London.12 Early research primarily explored the neural mechanisms behind how humans perceive, integrate, and make sense of art and aesthetic experiences.

Since then, the field of neuroaesthetics has expanded far beyond its early focus, engaging with growing evidence showing how visual arts, dance, architecture, digital media, and music influence brain function, physiology, and behavior. Advanced studies now reveal how aesthetic experiences deeply shape our biology via sensory pathways. According to neuroscientist Susan Magsamen, scientists are “also using mobile devices and ‘smart’ wearable sensors to measure changes in respiration, temperature, heart rate, and skin responses when people are experiencing or creating art.”13

[Susan] Magsamen and…Ivy Ross, authors of Your Brain on Art…make the case that engaging in artistic activities results in the release of serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin, and that these chemicals enhance mood, promote relaxation, and reduce pain, anxiety, and depression.

These innovations are transforming our understanding of how the human body and mind interact with aesthetic experiences and reveal something fundamental: our aesthetic sensibilities are deeply embedded in our daily lives. They play a significant role in everyday conscious and unconscious decisions—from choosing a love interest or a new home to how we respond to the presentation, temperature, taste, and smell of food. We are drawn to certain sounds and voices while cringing at others, and find certain colors, combinations of colors, and patterns calming and others overwhelming.

While the adage beauty is in the eye of the beholder holds some truth, our aesthetic preferences are also shaped by culture, historical contexts, and social bonds. Our surroundings profoundly affect us—whether we are immersed in nature; experiencing thoughtfully designed living spaces that integrate elements like natural light, greenery, and soundscapes; or we are waiting in soulless doctors’ offices and moving through hectic crowds on exhaust-fumed streets.14 Our environments have a significant impact on emotional regulation, learning capacity, and stress levels.

Magsamen and cowriter Ivy Ross, authors of Your Brain on Art, also make the case that engaging in artistic activities results in the release of serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin, and that these chemicals enhance mood, promote relaxation, and reduce pain, anxiety, and depression.15 People who engage in the arts tend to live longer. According to Magsamen and Ross, rigorous studies by epidemiologist Daisy Fancourt show that “the arts help cardiometabolic diseases, maternal healthcare, early childhood development, and more. But perhaps the most stunning fact…is what the arts do for overall longevity: People who engage in the arts every few months, such as going to the theatre or to a museum, have a 31 percent lower risk of dying early when compared with those who don’t. Even if you bring the arts into your life only once or twice a year, you lower mortality risk by 14 percent. The arts literally help you live longer.”16

And in a world where high-tech innovation often erodes opportunities for building relationships, arts prescriptions provide the added benefit of restoring social connections and fostering meaningful engagement within communities. Accordingly, doctors prescribing art are connecting their patients with aligned community resources that will enhance their health and wellbeing.17 Also, as with others who have found wellness through the arts, for Blodgett, the benefits extend beyond personal wellbeing. They have also reshaped her workspace and strengthened her connections to the world: art and physical movement became the keys that unlocked “the door to personal freedom and authentic community.”18 As she describes it, “They spark contagious vulnerability and allow a deeper sense of belonging to ourselves and to each other.”19

Recharge Rooms: The Power of Immersive Healing

Blodgett’s healing journey inspired the creation of the Brave House, a New York–based nonprofit that supports immigrant girls with legal and holistic services.20 In 2018, Blodgett was working exclusively with clients who had fled gender-based violence and sexual assaults in their country of origin. “I was their lawyer, helping fight for their human rights cases, their asylum cases, and trafficking cases,” Blodgett explained.21

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Due to its effectiveness on her own and her clients’ overall wellbeing, she was already integrating art, dance, and other movement such as stretching, walking, and yoga, in conjunction with (or even during) legal meetings and legal processes.22 However, she soon realized that her clients needed more than just winning legal battles. As with any social justice endeavor, participants also require a robust supportive community. They were coming to me asking, “How do I make friends? How do I get health insurance? How do I find a tutor?”23 This is when the Brave House became a “one-stop shop” where members could not only receive legal support, leadership training, school assistance, and such wellness services as therapy, meditation, and support for new and expecting moms, but also make friends and participate in dance and art classes.

Founded by artist–musician couple Jacob and Hae-jin Marshall, Applied Wonder began designing multisensory healing spaces in hospitals in New York to meet frontline workers’ needs in 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Incorporating dance and time in nature into her overall wellness plan helped Blodgett to recover from her condition and enabled her to show up in court with more poise, clarity of mind, and perspective along the way. Similarly, the Brave House clients felt more at ease and safe enough to share vulnerable details about their lives, breaking down feelings of isolation and cultivating a sense of belonging to a supportive community—which, research shows, is a crucial aspect of overall wellbeing.24

The Brave House became a reflection of what Blodgett needed to heal and, as evidence from neuroaesthetics research suggests, a glimpse of what healing could look like on a larger scale. This vision embraces a holistic approach25 that honors the interplay among our senses, our relationships, the environment, and the creation and experience of art. It challenges the traditional medical model—often confined to a doctor, a diagnosis, and medication—by advocating for a comprehensive, people-centered system that prioritizes multifaceted wellbeing.

In 2023, healing and wellness took on a whole new level of focus at the Brave House when the company EMBC (now Applied Wonder) offered to design an immersive healing room for the organization.26 Founded by artist– musician couple Jacob and Hae-jin Marshall, Applied Wonder began designing multisensory healing spaces in hospitals in New York to meet frontline workers’ needs in 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Wonder collaborated with artists, neuroscientists, and experts such as David Putrino, the director of rehabilitation innovation at the Mount Sinai Health System, to design rooms that blend neuroaesthetics with biophilic design—design that incorporates nature’s restorative effects into built environments.27

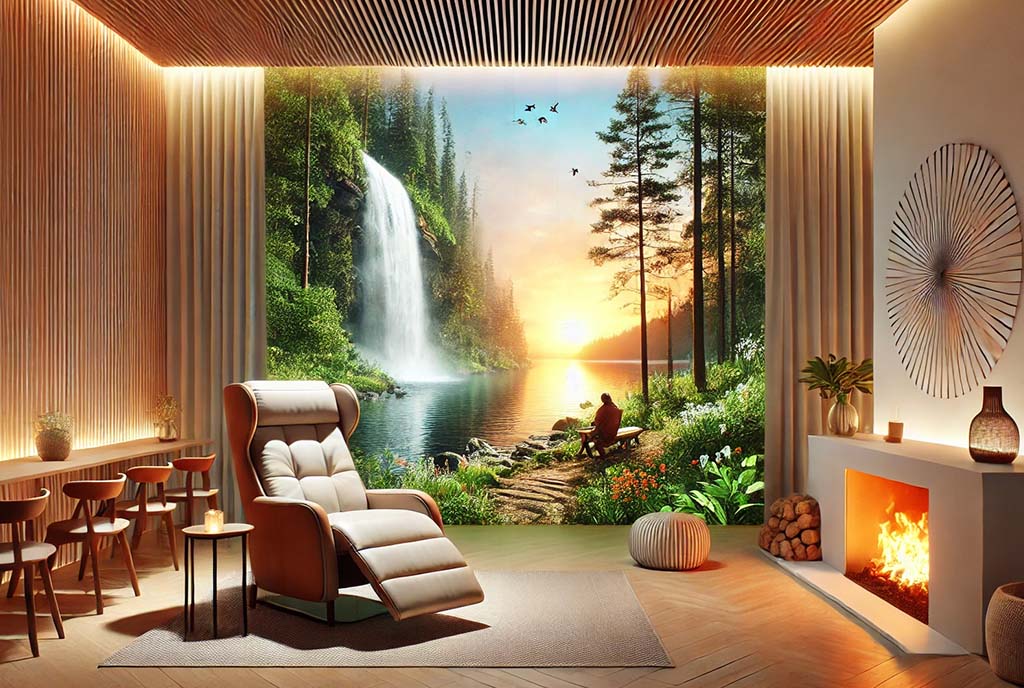

“We try to create a moment that includes music and color and light, haptics, vibrations, aromas,” said Jacob Marshall.28 In these immersive healing rooms, the participant sits in a comfortable chair and chooses from scenes like a waterfall in a forest, an ocean sunset, or a campfire by a lake, all previously filmed in nature. The selected scene is then projected onto a wall, evoking a state of soft fascination—effortless attention to soothing, natural stimuli, which research shows helps with stress reduction.29 Each film features its own soundtrack, created in collaboration with Grammy-winning artists and played in surround sound. The room also includes ambient lighting, gentle airflow, and aromatherapy to engage more senses and enhance the immersive experience. In a matter of minutes, one is transported to a serene environment for rapid restoration.

“While nothing compares to being physically in nature, if you apply this in the context of people with burnout, in 15 minutes their stress levels [have been shown to be] reduced by 60 percent. That would help them avoid a PTSD experience and instead move toward something called post-traumatic growth,” said Jacob Marshall.30

Blodgett calls their immersive healing room a “peaceful oasis in the heart of Brooklyn,”31 where people are shielded from the noise of traffic, subways, and ambulances. Members spend five minutes to an hour in the room to ground and regulate their nervous systems before or after legal meetings or intense sessions. “So, it’s a staple for us and for our team.”32

Art as Medicine

Beyond immersive healing rooms, prioritizing the arts as part of one’s approach to health and wellness is beginning to take root in different corners of the United States. CultureRx Initiative is a statewide effort in Massachusetts to “improv[e] health and well-being through cultural participation.”33 This initiative is implemented in part through Art Pharmacy, a company that collaborates with healthcare and community partners to prescribe creative and cultural activities for mental health and chronic disease patients.34 “Access to arts and cultural programming is an effective and readily available means of addressing mental illness, social isolation, and loneliness,” said Chris Appleton, founder and CEO of Art Pharmacy.35

Appleton reports that the majority of the company’s clients are women, and 46 percent identify as “Black/African American” and 28 percent as “LGBTQ+.”36 To serve marginalized and underserved communities, Art Pharmacy has partnered with Federally Qualified Health Centers, school-based mental health clinics, and Medicaid plans. “Options for socially grounded care can help reduce stigmas around engaging in an intervention, as therapy and meds can be highly stigmatized in certain marginalized communities,” observed Appleton.37 Half of Art Pharmacy members have indicated that they trust their provider more because of Art Pharmacy. The company also makes arts and culture more accessible by offering companion tickets, handling bookings and reservations, and providing transportation when necessary. Appleton recalled a teen member who, after a transformative experience at a ceramics studio, pursued an internship for continued support of her mental health. Appleton also described an elderly patient who was introduced to a crocheting class at her local senior center and became an active daily member to keep in touch with that community.38

Fortunately, savoring the senses and engaging in art and playful activities don’t require a massive budget, and need (primarily) just a supportive framework that offers accessible options—elements crucial for vulnerable communities. “Sometimes the most powerful medicine is free.”

Health scientist Tasha Golden, who led CultureRx’s pilot program evaluation, emphasizes the need for systemic change in healthcare. Golden’s neuroaesthetics research explores how the arts can improve public health and health equity by alleviating symptoms, speeding up healing, and enhancing mental health—helping us reimagine our systems and our world.39 “Wellbeing work is ultimately world-building work. And you can’t be about the work of wellbeing, unless you’re about the work of building the world in which that wellbeing is possible. And that’s fundamentally innovative work. It’s creative work. It’s imaginative work,” she said.40

***

To harness the power of art for healing and as preventive medicine, institutions, organizations, and communities are rethinking rigid and archaic means of interacting with their workday and life beyond work. They are reimagining their approaches more creatively, finding new ways to integrate art and beauty into their daily practices and existing settings and culture. They are incorporating biophilic design into the classroom, which greatly benefits neurodivergent students and teachers.41 They are tapping into the power of music to speed up recovery from surgeries.42 And they are using communal art as a way to bring about healing and social justice.43

These aesthetic-based models address not only inequities in access to holistic wellbeing practices but also the deep mistrust many marginalized communities feel toward the medical establishment. Historical and systemic injustices—including discrimination, exploitation, and neglect—have left many individuals and communities wary of conventional healthcare systems. When workspaces, schools, and community spaces incorporate art, biophilic design, and other sensory engagement as tools for healing, prevention, and community building, they provide free, meaningful pathways to mental and emotional health that don’t rely solely on conventional medical models.

Creating systems that integrate art into daily life is a step toward reducing health disparities, especially for communities experiencing high levels of stress, trauma, and limited access to culturally relevant, trustworthy, and affordable care. This approach not only empowers individuals but also creates an infrastructure where wellbeing becomes a shared, community-driven priority.

Fortunately, savoring the senses and engaging in art and playful activities don’t require a massive budget, and need (primarily) just a supportive framework that offers accessible options—elements crucial for vulnerable communities. “Sometimes the most powerful medicine is free,” said Blodgett, “and is either within yourself or just outside your window.”44 As for her personal health journey, Blodgett is in the best shape of her life. “I feel amazing. I feel better than I’ve ever felt before. I ran a marathon last year.”45

Notes

- Author interview with Lauren Blodgett, August 26, 2024.

- Ibid.

- Michael Rosenblum et al., “Treating human autoimmunity: current practice and future prospects,” Science Translational Medicine 4, no. 125 (March 2012): 125sr1; and DeLisa Fairweather and Noel R. Rose, “Women and autoimmune diseases,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 10, no. 11 (November 2004): 2005–11. And see “Program Snapshot,” “Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN),” National Institutes of Health, last modified April 12, 2024, commonfund.nih.gov/Diseases; and “Autoimmune Diseases,” National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, accessed December 20, 2024, www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/conditions/autoimmune.

- Gabriel Benavidez et al., “Chronic Disease Prevalence in the US: Sociodemographic and Geographic Variations by Zip Code Tabulation Area,” Preventing Chronic Disease 21 (February 2024): 230267.

- Hannah Hudnall, “US prescription drug usage nowhere near level described in viral video | Fact check,” USA Today, June 12, 2023, usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2023/06/12/experts-say-us-doesnt-use-87-of-global-prescriptions-fact-check/70290402007/.

- Dana Sarnak et al., Paying for Prescription Drugs Around the World: Why Is the U.S. an Outlier? (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Issue Brief, October 2017).

- Katherine Keisler-Starkey, Lisa Bunch, and Rachel A. Lindstrom, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2022 (Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau, September 2023).

- Author interview with Blodgett, August 26, 2024.

- Susan Magsamen, “Your Brain on Art: The Case for Neuroaesthetics,” Cerebrum (July 2019): cer-07–19.

- Monika Kvik, “Art as therapy: from history and different forms to scientific research and the future,” eu, June 27, 2024, karlobag.eu/en/psychology/art-as-therapy-from-history-and-different-forms-to-scientific-research-and-the-future-0ew64.

- Jessica DuLong, “Do this once a month and extend your life by up to 10 No gym required,” Life, but Better, CNN, May 31, 2024, www.cnn.com/2024/05/31/health/art-live-longer-wellness/index.html.

- Magsamen, “Your Brain on Art.”

- Ibid.

- María Luisa Ríos-Rodríguez et al., “Benefits for emotional regulation of contact with nature: a systematic review,” Frontiers in Psychology 15 (July 2024): 1402885.

- Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross, Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us (New York: Random House, 2023); and Magsamen, “Your Brain on Art.”

- Ibid., 109. And see “Social Prescription,” Mass Cultural Council,” accessed December 20, 2024, massculturalcouncil.org/communities/culturerx-initiative/social-prescription/research/.

- Meilan Solly, “British Doctors May Soon Prescribe Art, Music, Dance, Singing Lessons,” Smart News, Smithsonian Magazine, November 8, 2018, smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/british-doctors-may-soon-prescribe-art-music-dance-singing-lessons-180970750/; and Meilan Solly, “Canadian Doctors Will Soon Be Able to Prescribe Museum Visits as Treatment,” Smart News, Smithsonian Magazine, October 22, 2018, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/canadian-doctors-will-soon-be-able-prescribe-museum-visits-180970599/.

- Author interview with Lauren Blodgett, December 16, 2024.

- Ibid.

- “A non-profit for young immigrant women in Providing legal support, holistic services, & community,” the Brave House, accessed December 20, 2024, www.thebravehouse.com.

- Author interview with Blodgett, August 26, 2024.

- Author interview with Blodgett, December 16, 2024.

- Author interview with Blodgett, August 26, 2024.

- Sue Roffey, “Inclusive and exclusive belonging—the impact on individual and community well-being,” Educational & Child Psychology 30, 1 (March 2013): 38–49.

- Sujal Manohar and Tasha Golden, “The Role of Community Arts in Trauma Recovery,” International Arts + Mind Lab, Center for Applied Neuroaesthetics, Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed December 20, 2024, artsandmindlab.org/the-role-of-community-arts-in-trauma-recovery/.

- David Putrino et al., “Multisensory, Nature-Inspired Recharge Rooms Yield Short-Term Reductions in Perceived Stress Among Frontline Healthcare Workers,” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (November 2020): 560833.

- “Everything you need to know about biophilic design,” Space Refinery, April 30, 2024, spacerefinery.com/blog/biophilic-design-101.

- Author interview with Jacob Marshall, August 22, 2024.

- Diane Barth, “Stressed, Worried, or Overwhelmed? Soft Fascination Can Help,” Psychology Today, October 12, 2023, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/off-the-couch/202310/stressed-worried-or-overwhelmed-soft-fascination-can-help; and Avik Basu, Jason Duvall, and Rachel Kaplan, “Attention Restoration Theory: Exploring the Role of Soft Fascination and Mental Bandwidth,” Environment and Behavior 51, no. 9–10 (November–December 2019): 1055–81.

- Lorna Collier, “Growth after Trauma,” Monitor on Psychology 47, 10 (November 2016): 48; and author interview with Marshall.

- Author interview with Blodgett, August 26, 2024.

- Ibid.

- “CultureRx Initiative,” Mass Cultural Council, accessed December 20, 2024, org/communities/culturerx-initiative/.

- “Arts & Culture Improve Mental Health,” Art Pharmacy, accessed December 20, 2024, www.artpharmacy.co/.

- Author interview with Chris Appleton, August 20, 2024.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See Tasha Golden, “Arts on Prescription?,” Creativity, Wellbeing, & ‘How We Human (blog), accessed December 23, 2024, tashagolden.com/blog/arts-on-prescription. And see additional publications here: “Publications,” Tasha Golden, accessed December 20, 2024, www.tashagolden.com/publications.

- Author interview with Tasha Golden, September 5, 2024.

- Sheila Hartley, “The Power of Biophilic Design in Learning Spaces: What, How, and Why?,” EDspaces News, August 28, 2024, ed-spaces.com/stories/the-power-of-biophilic-design-in-learning-spaces-what-how-and-why/.

- American College of Surgeons, “Listening to Music May Speed Up Recovery from Surgery,” news release, October 18, 2024, facs.org/media-center/press-releases/2024/listening-to-music-may-speed-up-recovery-from-surgery/.

- Wilson College, “What Is Social Justice Art?,” Wilson College Online Blog, April 10, 2024, wilson.edu/resources/social-justice-art/.

- Author interview with Blodgett, August 26, 2024.

- Ibid.