November 2, 2015; Wall Street Journal

Concerned that the quality of our children’s education was sub-par and that improvement was key to our nation’s future, the Bush and Obama administrations put the resources of the federal government to work “reforming” our public education system. At the same time, support for the development of a new national approach to education came from a number of large foundations and individuals who shared the Bush/Obama perspective and strategy. Along with limiting the supposed power of teachers’ unions to block reform efforts, the development of a universal curriculum, known as the Common Core, and new standardized annual tests were key to this approach to educational improvement.

The Wall Street Journal recently took a hard look at how these key elements of the “reform” agenda were faring and found that despite the investment of billions of dollars by the U.S. Department of Education and the backing of foundations, the effort is foundering:

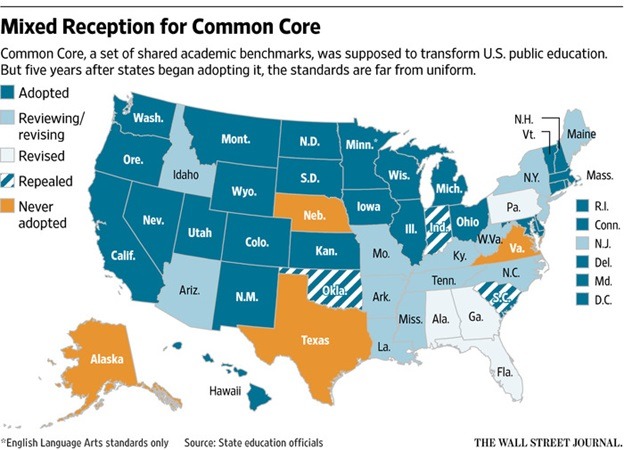

Five years into the biggest transformation of U.S. public education in recent history, Common Core is far from common. Though 45 states initially adopted the shared academic standards in English and math, seven have since repealed or amended them. Among the remaining 38, big disparities remain in what and how students are taught, the materials and technology they use, the preparation of teachers and the tests they are given. A dozen more states are considering revising or abandoning Common Core.

The WSJ also found that states and districts were also moving away from use of the standardized testing formats that were designed to go along with the Common Core:

An early priority of Common Core supporters was persuading states to use the same tests so student achievement could be better compared. But high costs have set back that goal as well. […] “Everyone had a clear desire to be able to compare student achievement results across a maximum number of states, ideally all fifty,” wrote Michael Cohen, president of education-policy group Achieve. […] That goal seemed within reach when 46 states joined two groups. The Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, or PARCC, and the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium were awarded a total of $362 million in federal funding to develop tests. Many states quit before the tests were ready to be used last school year, with some deciding to give tests specific to their states. PARCC now has only seven states and the District of Columbia using its test, and Smarter Balanced has 15.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The poisonous political climate that makes reaching consensus on policy and strategy nearly impossible made certain that the Common Core would become a matter of controversy, “a hyper-charged political issue, with grassroots movements pressing elected leaders to back off. Some conservatives saw the shared standards as a federal intrusion into state matters, in part because the Obama administration provided grant funding. Some liberals and conservatives decried what they saw as excessive testing and convoluted teaching materials.”

But the Common Core has greater problems than being caught up in the national political stalemate. High costs also proved to be a problem at the state and local levels—costs that include the need to have an up-to-date computer system to support the online tests.

The total cost of implementing Common Core is difficult to determine because the country’s education spending is fragmented among thousands of districts. The Wall Street Journal looked at spending by states and large school districts and found that more than $7 billion had been spent or committed in connection with the new standards. The analysis didn’t account for what would have been spent anyway—even without Common Core—on testing, instructional materials, technology and training. Education officials say, however, that the new standards required more training and teaching materials than they would otherwise have needed, and that Common Core prompted them to speed up computer purchases and network upgrades. Much more money would be needed to implement Common Core consistently. Some teachers haven’t been trained, and some schools lack resources to buy materials. Some states haven’t met the goal of offering the test to all students online instead of on paper with No. 2 pencils.

And while much of the initial funding has come from federal funding supported by major foundation investments, states and local school districts face the burden of ongoing costs that will need to be paid for by already-strapped local budgets:

The Philadelphia school district unveiled a plan in 2010 to implement Common Core and won a $500,000 grant from the Gates Foundation. But a budget crisis the next year resulted in nearly 4,000 layoffs, including of some [who were] putting the plan in place. “It was something of a perfect storm, where expectations were rising while resources were diminishing,” says Christopher Shaffer, Philadelphia’s deputy chief of curriculum, instruction and assessment.

The implications of this loss of traction, if not outright failure, are greater than just the sunk costs involved or the need for states to develop new curricular materials. With support for both of these elements of a national educational strategy losing local support, and with Congress’s present approach to extending the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) significantly curtailing the power of the Department of Education to impose its standards on states and local districts, the goal of ensuring that every child receives an equal, high quality education will be much harder to reach. The failure of a federally driven effort will return responsibility for reaching that goal to each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. And that prospect should be troubling, given the varying commitment to quality education among states.—Martin Levine