Deaths, Near Deaths, and Reincarnations: Part 2 of 5

Editors’ note: This article is featured in NPQ’s new, winter 2014 edition, “Births and Deaths in the Nonprofit Sector.” This is the second part of NPQ‘s mini–case studies on the death, near death, or reincarnation of five organizations. Click here to read part 1.

How do you spark a national conversation about higher-education policies, gain the attention of legislators and other policy-makers in every state across the country, evaluate the success of higher education in each state, and present the data so that the concepts are easy for people outside the field to understand? You issue a statewide higher education “report card,” and then you call the press.

From 2000 to 2008, the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education issued five biannual reports titled Measuring Up. States were graded in six areas: preparation, participation, affordability, completion, benefits, and learning. There were many bad grades—Ds and Fs—for many of the states. And, not surprisingly, many people were upset. But it got them talking about higher education.

Establishment of the National Center

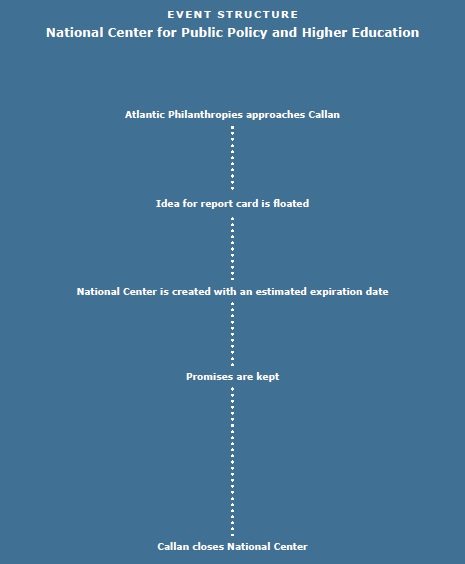

The idea for the National Center started in the late 1990s, when Patrick M. Callan, director of the nonprofit Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), was approached by Atlantic Philanthropies.1 Callan was well known in higher-education policy circles, as he had been working in the field since the early 1970s. Atlantic wanted to examine higher-education policies among the states and help them to set their agendas for the future, so Atlantic contacted Callan. The staff and the board of directors of HEPI, under Callan’s leadership, began eighteen months of intensive research. Could Atlantic’s vision be implemented? If so, how?

One idea was a report card on higher education. As Callan described it, his team liked the idea of a report card that would evaluate state performance in higher education regardless of the different policies that had been adopted state by state. In addition, the report card would gauge the success of higher education from the students’ perspective. Quality in higher education had always been measured through accreditation, which is centered on the institution; Callan hoped that the report card would change that focus.

HEPI did a yearlong feasibility study to see if there were enough data that would be relevant to good policy. They concluded that enough data existed and that a report card was an idea worth trying. At the time, Callan told me, they didn’t know if it was going to work or what the response would be.

HEPI had previous experience evaluating the performance of higher education, but not on this scale: HEPI was established in 1992 to conduct nonpartisan analyses and policy studies of higher education and disseminate the results through publications and public programs. From 1992 to 1997, HEPI sponsored the California Higher Education Policy Center, which addressed the future of higher education in California.2

Callan’s success in California had clearly interested Atlantic, but his experience had taught him that if the report card idea attracted attention there would be controversy. “We never set out to create gratuitous controversy in California, but if you do something with integrity, you are going to piss people off,” Callan said. Atlantic and subsequent funders like the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Ford Foundation knew this was a risk but over the course of the National Center’s existence never wavered in their support nor pressured Callan to “back off.”

The next step was creating an entity to support the report card; that entity, the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, was officially announced in March 1998 by James B. Hunt Jr., then governor of North Carolina. Governor Hunt served as the chair of the National Center’s board, and his participation in the endeavor gave it and its products instant credibility.3

Callan envisioned the National Center as an independent policy forum, much like the Truman Commission in the 1940s and the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education in the 1970s. He also envisioned that, like those two commissions, the National Center would exist for a period of time then cease operations.

Measuring Up and Other Projects

Measuring Up. The first edition of the report card was issued in 2000. The National Center’s goal was to show the states what they were doing well in higher education and what they were not. If a state was not doing something well, policy-makers in that state could look at other states for examples of success. In grading the states, performance was the only measure; the policy of the states was not analyzed, and the states did not get “points” for trying. “The ‘grades’ were just a device to get the message out,” Callan explained.4

Callan knew that the higher-education establishment would likely not be receptive to the idea and might choose to ignore it; thus, in order to have impact, the National Center would need to get media attention on the report. The center actively sought that attention, and the strategy worked. Callan and his staff members were invited to speak to legislatures around the country, as well as to organizations like the National Governors Association and the National Conference of State Legislatures. Sometimes they were met with enmity, but, according to Callan, they “were happy to be challenged.”

Associates Program. In 2000, the National Center established an associates program designed to foster the professional growth of individuals in higher education. As Callan put it, “If an organization is going to be sustained, it is all about developing people.” The program’s purpose was to give early-career and mid-career individuals an opportunity to meet with senior people in the field to share knowledge and consider broad policy issues.

One of the most important goals of the program was diversity of all types: “demographic, professional, and geographic.” To that end, the first group consisted of ten individuals from different parts of the country, who met for three extended weekends throughout the course of a year. The program operated for seven years, and nearly one hundred people completed it. The participants evaluated the program annually, and high levels of satisfaction were reported.5

National CrossTalk. National CrossTalk was the National Center’s periodical between 1997 and 2011. Published three to four times annually, it was designed to be a vehicle for exploring the possible solutions to the higher-education issues brought to light in Measuring Up. As Callan described it, “Those of us in social science, we can be good analysts but lousy storytellers. I knew a good story would help people connect with and understand the issues.” This approach was all part of the National Center’s strategy to help make higher-education policy issues part of a national discussion.

Callan was clear that the purpose of CrossTalk was not to promote the National Center; it was to examine how policy issues impacted real people. To that end, he hired a former Los Angeles Times education reporter to be the senior editor of CrossTalk, and CrossTalk hired freelance reporters to examine higher-education stories from both sides. The reporters were never told what position to take. NationalCrossTalk was very successful, in large part because, said Callan, “if you make it about the issues, and less about ‘me versus you,’ the more likely you are to be listened to.”6

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Closing the Center

When the idea of the National Center was set forth in a concept paper in 1998, one of its missions was “to conduct public policy research and studies in areas relevant to the higher-educational needs of the nation over the next 15 to 20 years.” When the National Center announced its closing in a Cross-Talk editorial in December 2010, Callan declared that at its inception, “we expected the National Center to operate for about ten years.”7 When asked about this apparent discrepancy, Callan acknowledged that although he had not announced a specific time frame for the National Center’s existence, it was always understood that it would have a finite life of about a decade—notwithstanding the fifteen to twenty years of public policy and research the center originally intended to conduct.

To that end, Callan kept the staff relatively small—fifteen employees at the most. Although there was enough funding to double the staff, Callan felt that “smaller is good.” Not only did the small staff allow the National Center to be nimble in response to changes, it also enabled all employees to be part of the conversation. And, because the center was not a large organization, it would need to reach out to other groups involved in higher-education research and use them as resources, helping to overcome the “us versus them” mentality that sometimes pervades higher-education research.

Why

The question that begs to be asked is, Why create a nonprofit organization with an expiration date? Callan’s response was simple: “No one asked me to create a center for the ages.” But the reasons are a little more complicated than that.

First, Callan has done this before. When he helmed the California Higher Education Policy Center, he announced at the outset that it would operate for five years only—and it did. In retrospect, he regretted the specificity with which he had stated its demise (indeed, he admitted to feeling that the deadline had been a little too rigid and thus had been intentionally vague about how long the National Center would operate when it first opened). But he stayed focused on his mission and successfully completed it in the five-year time frame. Callan is, clearly, comfortable working on time-restricted projects (of course, undertaking policy research in a discrete subject area like higher education lends itself more easily to a finite time frame than some other nonprofit goals, such as, for example, ending world hunger).

Second, the impermanence of the National Center gave Callan a lot of freedom. For Callan, an organization that is not created to be permanent can take more risks, and “you need to take prudent risks to change policy.” A permanent organization might be worried about losing funding if it takes certain policy positions. Callan did not have that pressure. Callan’s funders were 100 percent supportive of the National Center’s mission, but, he said, “if the funding hadn’t been there, I would have just closed the place.”

Third, the National Center’s most visible product, Measuring Up, was a victim of its own success. This report card on the states got a lot of attention, especially in its first year. By the time the fifth edition was published, in 2008, it had, according to Callan, become part of the landscape. Politicians and other policy-makers, who at first reacted with anger and suspicion, eventually learned to use Measuring Up for their own purposes.8 In addition, much of the shock was gone after the first edition, since people knew what to expect. Callan opined: “Are you going to keep doing [something like the report cards] until no one reads your reports? Or until no one funds you?”

How

Unlike many nonprofits, the National Center did not close because of lack of funding—it was well funded at its inception and throughout its life. The National Center began with a grant from Atlantic Philanthropies, and in 2002 and 2003 Atlantic gave the National Center grants totaling $6.5 million and $2 million, respectively.9 Even at the end of its life, the National Center was still being funded. In 2011, the year it closed, it received $330,290 in grants and contributions.10

Callan has said that the National Center operated longer than expected so that it could produce the 2008 edition of Measuring Up, which was its last report card. The decision to close in 2011 was made at the same time as the issue of the final report card (most of the center’s funding was structured as three-year grants, so the board of directors had agreed to stop seeking funding three years prior to the center’s closing.) Staff were also fully aware of the anticipated closing and thus were able to make plans for subsequent employment.

After Closing

At the time of the National Center’s closing, Callan hoped that the report card would be continued by another organization. He acknowledged that the report card would have to be reformulated, in part because there are better data now. Although several foundations were approached with the idea, however, none accepted the challenge. Callan believes the country suffers without the report card, not only because it fueled public discourse about the issues but also because it gave people at the state level leverage to advocate for changes in policy. Callan similarly hoped the Associates Program would be adopted by another entity, but to date it has not.

Although the National Center was closed in June 2011, its umbrella organization, HEPI, filed a Form 990 with the IRS for 2012.11 When asked about this, Callan said that he has kept the National Center alive as a legal entity in order to “house” projects for individuals who have funding but do not have a nonprofit in which to “park” their endeavors. He made it clear that he’s not looking for business and that the National Center will likely “go away someday.”

Notes

- Unless otherwise specified, all direct and indirect quotes from Patrick Callan are from an interview with the author.

- The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, “Reports and Publications: Other Higher Education Reports and Resources,” accessed October 8, 2014, www.highereducation.org/reports /reports.shtml.

- Doug Lederman, “(Not Really) Measuring Up,” December 3, 2008, Inside Higher Ed, www.inside highered.com/news/2008/12/03/measuring.

- William Chance, The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education’s Associates Program (San Jose, CA: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, May 2009), 3, www.highereducation.org/reports/associates/associates_report.pdf.

- Ibid., 4.

- Patrick M. Callan, Concept Paper: A National Center to Address Higher Education Policy (San Jose, CA: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 1998), 5, www.highereducation.org /reports/concept/concept.shtml.

- James B. Hunt Jr. and Callan, “Editorial,” National CrossTalk (San Jose, CA: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, December 2010).

- See, for example, Lederman, “No Grades for States This Year,” Inside Higher Ed, December 1, 2010, www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/12/01/measuring_up.

- The Atlantic Philanthropies, “National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education: Grantee Summary,” accessed October 15, 2014, www.atlanticphilanthropies.org/grantee/national-center-public-policy-and-higher-education.

- “Form 990: Return for Organization Exempt from Income Tax, FY2011, Higher Education Policy Institute,” filed December 14, 2012, accessed October 8, 2014, www.guidestar.com/organizations/77-0313194/higher-education-policy-institute.aspx#forms-docs.

- Ibid.

Barbara Berreski is director of Government and Legal Affairs of the New Jersey Association of State Colleges and Universities (NJASCU) and a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania.