Corporate subsidies these days are ubiquitous. Greg LeRoy and Arlene Martinez of Good Jobs First report that the state and local tax subsidies corporations receive alone total $95 billion. In 2022, they noted, this included eight awards for $2 billion each. Anyone who says there is no money for needed social services should look again. The money is there—it’s just going to the wrong places.

An important subset of these giveaways is the megaproject, typically involving sports stadiums. Earlier this year, voters in Kansas City decisively rejected a nearly $2 billion subsidy deal for the football and baseball teams by a margin of 58 to 42 percent. This is just one instance among many. Across the United States, at least a dozen sports teams—often owned by White billionaire families—are aggressively pushing for more than $14 billion in public subsidies to build private stadiums. This includes my hometown of Chicago, where the Bears and the White Sox are lobbying hard for a combined $3.4 billion for new facilities.

Anyone who says there is no money for needed social services should look again. The money is there—it’s just going to the wrong places.

What can be done to stop billionaires from subsidizing their sports teams with public dollars? Our successful campaign to stop a multi-billion-dollar subsidy effort to bring the Olympic Games to Chicago offers lessons that have broad application elsewhere.

The Battle of the Bid

In 2008, Chicago was riding high. Adopted native son Barack Obama had just been elected president. Using that momentum, Mayor Richard M. Daley, backed by Chicago business leaders and the political establishment, sought to bring the 2016 Summer Olympics to Chicago. Daley, who had been the city’s mayor since 1989, had never lost a major political campaign or policy initiative. The Chicago 2016 Bid Committee spent $100 million on the bidding process alone, according to one estimate.

But was this really a good idea for the people of Chicago? A small group of concerned citizens, including myself, formed No Games Chicago, a grassroots organization determined to stop the bid and its potential impact. With no office and no paid staff, we did the due diligence that should have been done by the established civic watchdogs and media outlets.

No Games Chicago was a group united by a common cause. Some of our allies were:

- Deborah Taylor, a member of Southside Together Organizing for Power (STOP) and a leader with the Lake Park East Tenants Association

- Karen Lewis, then president of the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (CORE ), soon to become the president of the Chicago Teachers Union

- Willie J.R. Fleming, an organizer with the Coalition to Protect Public Housing and the Chicago Independent Human Rights Council, who became executive director of the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign

Two pivotal organizers were Bob Quellos, an architect at SWWB Studio in Chicago and longtime Southside activist, who played a key media relations role; and Ramsin Canon, a lawyer and consultant. My own role was webmaster and lead researcher.

After months of quiet preparation, we went public with a community forum at the University of Illinois Chicago’s Student Center in late January 2009. From there, we quickly became a trusted source of opposition and information on the Olympics and their impacts on host cities. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was to meet in Copenhagen on October 2, 2009, to award the 2016 Olympics to one of four finalist cities—Chicago, Madrid, Rio de Janeiro, or Tokyo. At the time, the common wisdom was that the bid was Chicago’s to lose.

Megaprojects…tend to fail to deliver promised benefits. Worse, they come with a staggering set of negative consequences.

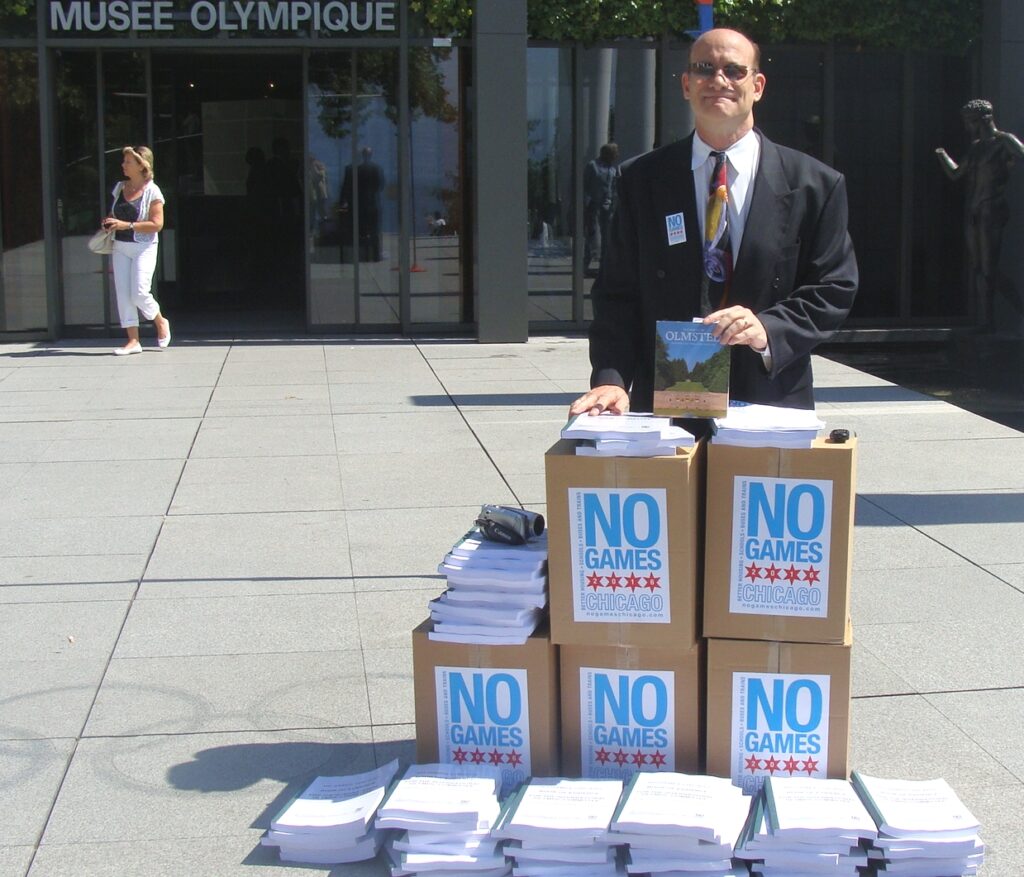

Throughout the eight-month public campaign, No Games Chicago engaged in a relentless and creative operation to convince the members of the IOC to vote “no”, including two protest rallies and two trips into the IOC’s world.

The first was in June, when we went to their international headquarters in Lausanne to crash a gathering of the four finalist cities, to deliver materials to the IOC stating our case and documenting the reasons why Chicago should not host the Olympics. And then, in late September, we went to Copenhagen to deliver another set of materials.

Throughout this period, we maintained a robust website and produced an informative email newsletter. We attended or produced dozens of community meetings, and our spokespeople gave dozens of interviews. We emailed messages directly to the members of the IOC for 70 days leading up to the vote. On October 2, 2009, Chicago was ejected from the hunt on the first vote on that cold, crisp Friday morning—a testament to the power of grassroots activism.

The Principles Behind the Struggle

Our coalition opposed bringing the Olympics to Chicago, which has parallels with the many kinds of megaprojects cities might face. Research shows that megaprojects like the Olympics, the World Cup, private stadiums, and large “city-within-a-city” private developments tend to fail to deliver promised benefits. Worse, they come with a staggering set of negative consequences. Here is a comprehensive list taken from the article “The Mega-Event Syndrome” by Martin Müller, published in 2015 by the Journal of the American Planning Association.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

| Symptom | Consequences |

| Over-selling benefits |

|

| Under-estimating costs |

|

| Event takeover |

|

| Public risk taking |

|

| Rule of exception |

|

| Elite capture |

|

| Event fix |

|

To this depressing list, we need to add a few other consequences of hosting an event like the Olympics:

- Shredding of civil liberties: As occurred in Paris in 2024, police routinely sweep the streets of “undesirables” and the unhoused.

- Expansion of the surveillance state: The Olympics—as law professor Anne Toomey McKenna notes—are a venue famous (or infamous) for “pervasive and persistent surveillance before, during, and after the Games.”

- Corruption of local politics: In addition to the well-documented instances of Olympic bribery, political meddling involved in hosting a megaproject often escapes notice. Chicago was set to give significant oversight of the Games to two key aldermen (city councilmembers), one of whom was later convicted of multiple accounts of fraud and bribery and is now in prison; and a second who has been indicted for corruption and is awaiting trial. Had these corrupt politicians had access to Olympics wealth, they would have been positioned to suppress independent progressive politics in Northern Illinois for a generation.

Three Key Stages to Effective Organizing

Is there a project that needs to be stopped in your hometown? There are the three major stages that you will need to navigate, listed below. They are detailed here with a set of resources you can access.

Stage 1: Get Smart Before You Fight

Before you critique, you must understand the basics.

- Understand municipal budgeting: Learn the basics of the city budget process.

- Know the relevant history: For example, if the project involves the Games, read up on the Olympics and their history.

- Learn about megaprojects’ impact: To oppose megaprojects effectively, it helps a lot to be well informed about past projects. There is a ton of literature out there.

- Develop your narrative: Brush up on framing and storytelling. Do not accept project proponents’ narrative assumptions!

- Use data effectively: Part of being a compelling storyteller is using data, maps, and visualizations; and making those facts relevant and hard-hitting for constituents.

- Understand organizing basics: There is an art and a science to pulling people together to fight a common enemy and to seek and activate solutions to long-standing ills.

Stage 2: Get Ready for Your Campaign in Private

The second stage is the planning stage.

- Do your research: Go deep and wide. You must be very well informed on the project you are fighting. That may mean connecting with people and campaigns from other places and times.

- Build coalitions: Your enemy’s enemy is your friend. Ask who will be harmed by the project that you are fighting. Think creatively about allies. Expose the supporters of the project you are fighting and the people and organizations paying for it.

- Prepare your infrastructure: You will need to have a website, social media presence, a robust email tool, and a bank account. These tools will be essential to hold your message and act as a hub for those who want to support you or cover you in the media.

Stage 3: Go Public

Economic or community development…must replace a “thing focus” with a “people focus.”

Once you have done your research and built your coalition, then it’s time to launch your campaign and begin to build the power you need to achieve victory.

- Develop clear messaging: You need an identity—perhaps even a logo—to cement your presence in the public’s mind and, along with it, a consistent and tight message—about why the project you are fighting is bad and why people should believe you.

- Communicate to decision-makers: Decision-makers are sometimes referred to in organizer-speak as “the target.” Figure out who knows them and how you can reach them directly.

- Deploy your ground game: Organize forums, protests, rallies, and door-knocking campaigns as part of showing up and building your case. Ask for money and volunteer time from your constituents and develop new leaders from the people you encounter.

- Be creative and dramatic: You will need to be nimble, flexible, and highly creative as you take on megaprojects, as they are often backed by the city’s most powerful and wealthy people. Elites do not like to be mocked, so please use humor and scorn when you can. For example, Chicago is famously corrupt, so No Games organized a “Clout Fest” that solicited alternative Olympic logos and original music and even parody news clips. No Games Chicago went to the international headquarters of the IOC to say, “No thank you!” and this one action brought us headlines—not to mention close contact and credibility with IOC members.

- React swiftly, speak powerfully: Once you enter the field of battle, be prepared to analyze and respond to the communications of your opponent. No Games Chicago instantly responded to actions and statements made by the Chicago 2016 Bid Committee and their allies. For example, after we had made a huge stir in Lausanne, Mayor Daley was caught in his lie that the Games would involve no subsidies. To counter a firestorm of protest and bad media, he ordered the committee to hastily convene 50 meetings—one for every ward—during the summer and early fall of 2009. No Games was ready, and we were at every one of those meetings—with signs, flyers, and prepared statements.

- Acknowledge, celebrate, and document: Lift up the voices of everyone on your team, celebrate your wins, and learn from your setbacks. Put personal differences aside for the greater good and share lessons and tactics. Build infrastructure so you don’t need to reinvent the civic wheel whenever a megaproject threatens. Please keep a website alive after the fight and consider writing a history of your work as I have.

Communities Fighting Back

Around the country, many communities are fighting megaprojects. Here are a few:

- NOlympics LA: An offshoot from the organizing of the Democratic Socialists of America Los Angeles, this group is fighting to mitigate the harms of the upcoming 2028 Games and to advance the cause and reality of affordable housing for the city.

- Stop the Arena: This people-powered effort killed a planned public subsidy of $1.5 billion for a stadium for the Washington Wizards and Washington Capitals that was to be built in Alexandria, VA.

- Thoughtful Progress for the I-88/Route 47 Corridor: This grassroots organization in Kane County, IL, is fighting a mega-development pushed by the billionaire Crown Family that has been awarded a public subsidy of up to $109 million.

- Unite Oregon: I just facilitated a two-day workshop in Portland called “Public Money 101” to help the stakeholders of this grassroots community organization understand the city budget and the implications of six new tax increment financing districts (TIFs) that are being pushed forcefully there.

Beyond Megaprojects

Sometimes it seems like our cities have been turned into back offices for the real estate industry. What passes for “economic development” seems limited to real estate deals. What can we offer our communities instead of another “city-within-a-city” development or domed stadium that looks like an alien spacecraft?

One important lesson from our struggle in Chicago: you can fight City Hall and win. We did, and it was immensely rewarding to know we saved Chicago from an economic disaster on the order of the Chicago fire of 1871. Rio was awarded the 2016 Olympics, and, in inflation-adjusted dollars, they spent over $24 billion! “Whew,” is all that I can say.

Beyond that, I would like to offer a simple refocusing of what we mean by economic or community development. In short, we must replace a “thing focus” with a “people focus.” Look to the people who live in the community that needs “development” and ask them what they need. Ask them what is missing and what will make their lives more secure, joyful, and prosperous. I am quite certain that it will not involve a Starbucks, a high-end shopping mall, or a domed stadium.