January 20, 2020; New York Post and Eater (New York)

Nonprofits are often encouraged to innovate. In fact, we are told that when we fail, we should celebrate the noble attempt. However, the example of the recent closing of New York’s Colors restaurant reminds us that we should be careful to consider who might be hurt as a consequence, and what we must do to mitigate and inform partners about the risks.

When the World Trade Center towers fell, the jobs of hundreds of restaurant workers were gone. Motivated by a desire to help find them new jobs, Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC United) emerged and found a wider purpose: “to organize workers to improve wages and working conditions throughout the restaurant industry.”

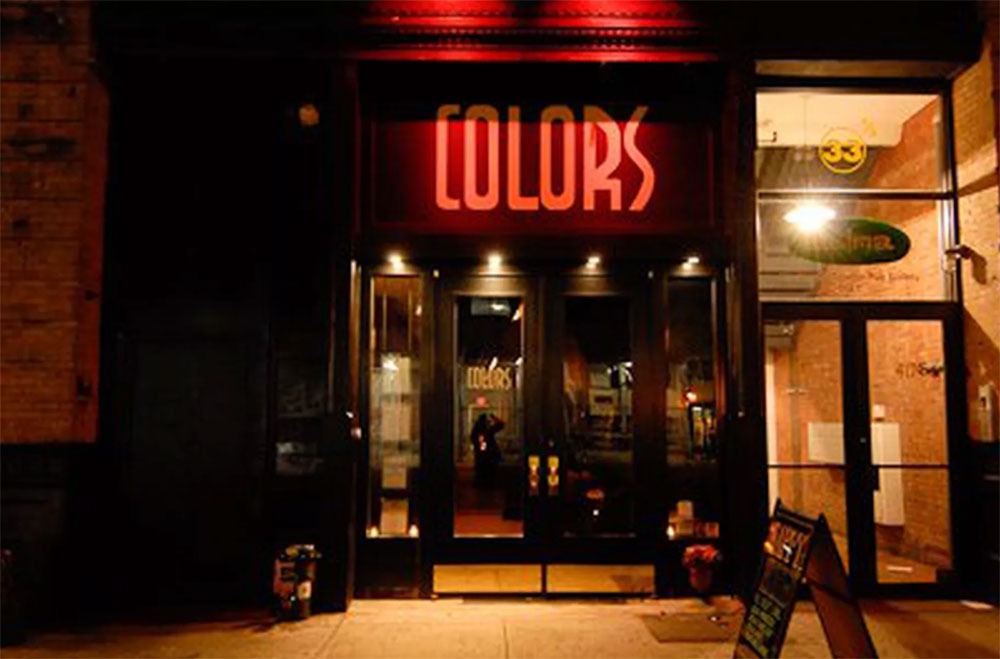

Hoping to establish a model alternative that would adhere to these values, ROC United opened Colors in 2006, designed to be a business where, as described by the New York Times, “workers believed in the mission of the restaurant to lift them up and treat them fairly. Some Restaurant Opportunities members were even offered a stake in Colors during the planning stages, when the concept of the restaurant being a worker-owned cooperative had been discussed.”

But making this vision work proved challenging, and even with adjustments to menus, and location, the model began to run aground, paying employees erratically and not maintaining inventory sufficient to the restaurant’s needs. The restaurant stayed open for 11 years, but given that Colors closed its doors amidst multiple lawsuits from unpaid employees, it would appear the restaurant should have closed earlier.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

One might hope ROC United—a large nonprofit with chapters in ten cities, a budget in the millions, and a track record of success in its advocacy work—might have learned from this failure. But when you reopen a restaurant in December 2019, only to close it again the following month, it is hard not to wonder what was going on. The restaurant stayed open only six weeks. Was working capital raised to give the business a chance to succeed through the predictable bumps of a New York City restaurant startup coupled with an odd business model?

Employees were blindsided, but Sekou Siby, the group’s executive director, told the New York Post that this is just part of the organization’s learning process. “We are assessing the financial situation,” Siby says. Siby calls the quick opening and closing “a test drive, to analyze what is possible.”

Maybe ROC United paid for its learning in the losses it experienced, but the program’s employees reportedly were devastated. Head chef Sicily Sewell-Johnson told Eater New York the announcement of the closing “wrecked the staffers who invested months into the reopening under the impression that it would be permanent.”

There is a rule in systems theory that “foresight is morality.” And with nonprofit innovation comes this requirement to consider the possible scenarios that may play out, inform all clearly so that they know what part of the risk they carry, and have a little something set aside to reward participants for sharing that load.

Bottom line: risk favors the prepared. There is no shame in a nonprofit launching a business and failing. There is shame, however, in not integrating the lessons from failure or in offloading the costs of failure onto the people the nonprofit seeks to serve.—Martin Levine