September 24, 2019; Hyperallergic

New York’s American Museum of Natural History, like many other revered nonprofit organizations, has been pushed to confront its racist roots. With an exhibit recently opened about the sculpture that greets visitors entering its building, the museum has chosen to keep the artwork in place, but is providing a more complete picture of its subject, including an explicit critique of the sculpture’s celebration of imperialism.

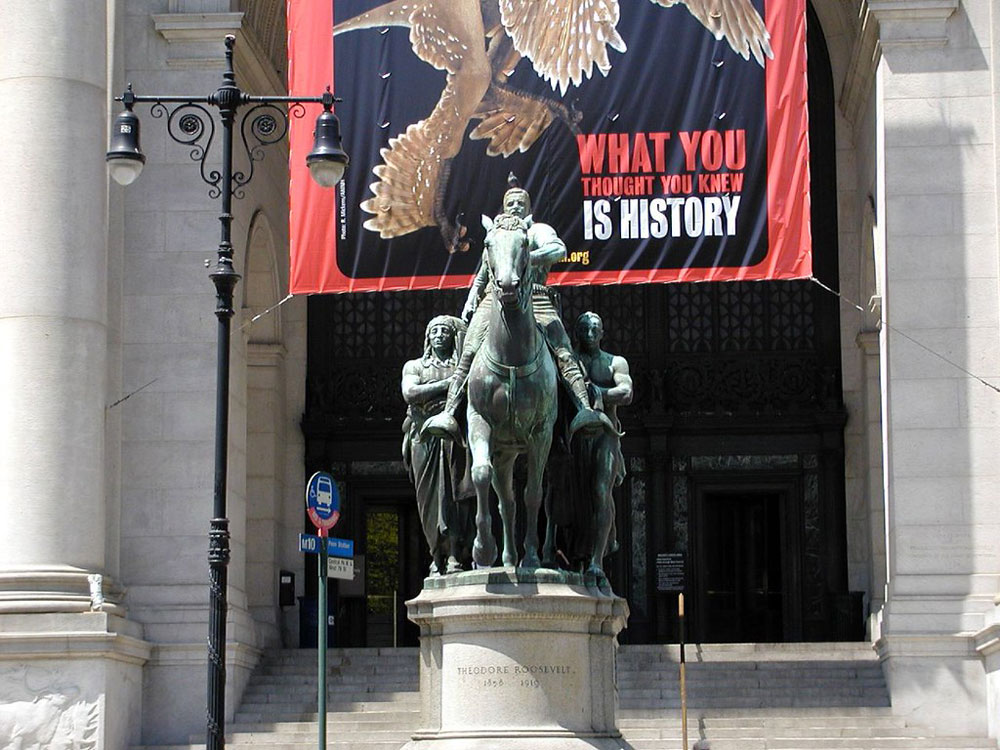

At the museum’s entrance, President Teddy Roosevelt, astride a horse, towers over a Native American and an African. The work has been described by critics as embodying the message of white supremacy. In 2017, protesters from a group calling itself the Monument Removal Brigade (MRB) splattered it with red dye to make this point. According to a statement from the group published by Hyperallergic, they wished to call attention to Roosevelt not as a former president but as “a white supremacist and imperialist.”

As opposed to Roosevelt as defined by inscriptions on his statue’s base and along the terrace’s parapet wall: explorer, scientist, conservationist, naturalist, ranchman, scholar, statesman, author, historian, humanitarian, soldier, patriot. MRB specifically calls out his role in the Spanish-American War, which led to the US’s annexation of Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines as well as his staunch endorsement of eugenics.

Faced with growing protests over this and other pieces of offensive public art, the City of New York assembled the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers to provide guidance. When it completed its work, the Commission recommended keeping the offending sculptures in place but adding contextual information for visitors to learn from and commissioning new pieces depicting prominent personalities of color. The leadership of the AMNH took this guidance and, rather than remove Roosevelt, created a temporary exhibit, located in a hallway leading to the Museum gift shop, that examines Roosevelt both as a naturalist and a eugenicist.

The exhibit, Addressing the Statue, “examines various aspects of the monument and the president it memorializes. It explores the history of the statue’s design and installation, who the men at the bottom of the statue may represent, and Roosevelt’s own racism. The museum examines its own complicity at points, too, with references in the video to its exhibitions on eugenics in the early 20th century.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Curator David Hurst Thomas from the AMNH Division of Anthropology, speaking to Hyperallergic, explained the museum’s vision: “Some today view the statue as heroic. Others see the statue as a blatant symbol of racial hierarchy. Addressing the Statue sidesteps such simplistic binary thinking in favor of multiple perspectives and multiple voices.”

Is that enough to turn the negatives into a positive? According to the New York Times:

Mabel O. Wilson, a professor of architecture and African American and African diaspora studies at Columbia University who served on the city commission to reconsider the statue and was consulted on the exhibition, still wants to see the statue moved elsewhere. “I think it’s a starting point, both for the institution and its visitors,” said Dr. Wilson. “I hope it prompts visitors to pursue their understanding of history in a way that really starts to wrestle with history and these truths that we see being told.”

Nick Mirzoeff, writing in Hyperallergic, finds the temporary exhibit does little to overcome the harm that was done, nor does it demonstrate the museum has recognized its true history:

The exhibition balances Roosevelt as both a racist and the host of African American leader Booker T. Washington at the White House. Does this in fact constitute a balance; that is, are these conflicting worldviews of equal validity or weight? A recent New York Times op-ed noted that racism was “central to Roosevelt’s vision for America, and not just an artifact of his time and place.” Indeed, he gets an entire chapter in Princeton professor Nell Irvin Painter’s History of White People. There’s no mention at AMNH of his support for eugenics or his 1905 speech that popularized the supposed threat of “race suicide.”

This debate captures the challenge to every institution that must reconcile with its history. Removing honors, names on buildings, artwork, and exhibits because they mask the evils of the past may offend some to whom they remain important and carry positive meaning. Does adding a broader context—and the learning that may occur by doing so—produce a satisfactory resolution? For the American Museum of Natural History, does keeping Roosevelt standing tall, but surrounded by a fuller explanation, truly fulfill its mission and meet its values, or is it just a compromise to reduce the cost of change? Not easy questions to answer, but important ones.—Martin Levine