When a disaster hits, communities look to all levels of government, nonprofits, faith groups, insurance providers, and philanthropy to help them recover. They need help urgently, and they want it immediately.

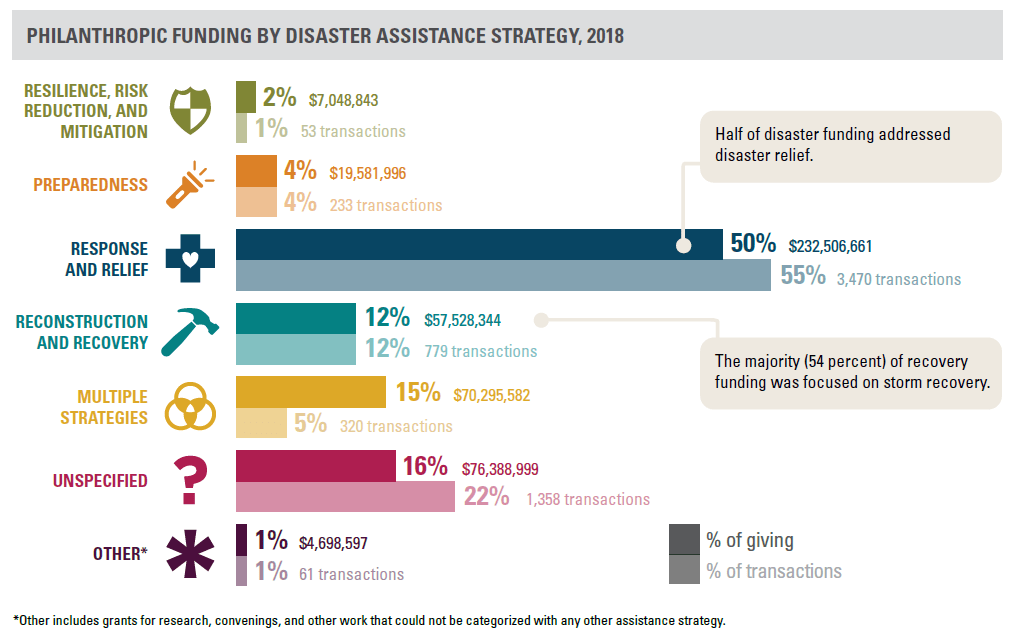

But funding does not come in at the pace households and communities need for an effective recovery. When it does come, it isn’t enough, has too many strings, and doesn’t meet residents’ immediate and long-term needs. In the 2020 Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy report produced by the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP), where I work, in collaboration with Candid, only two percent of funding was for resilience and merely four percent for preparedness.

The Cost of Disasters

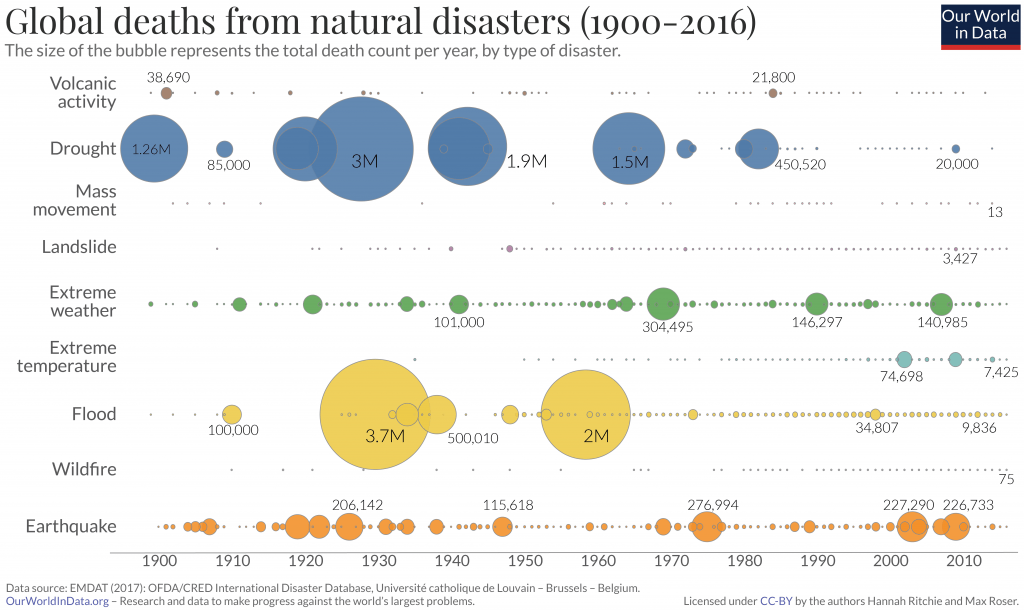

When I began to research disasters a decade or so ago, I hoped that prevention and mitigation fixes would reduce the need for extensive response and recovery. While the numbers show this is not the case financially, this has happened in the area of morbidity and mortality. Due to improved construction regulations and advance warning systems, disasters cause fewer deaths than they did 50 years ago.

As the chart below shows, deaths from most types of disasters have decreased. That said, deaths from extreme temperatures—a kind of disaster that didn’t even appear on the chart at the beginning of the last century—are growing rapidly. This is linked to the intense heat many communities now experience. In fact, in the US, with the exception of the COVID-19 pandemic of the past year-and-a-half, these days heat kills more people annually than all other disasters combined.

Disasters are also becoming more expensive, in part because there are more people and more “stuff” at risk of being damaged or lost. Therefore, a major hurricane today will cost more than one of a similar intensity did 10 or 20 years ago. Population growth often means property development in at-risk neighborhoods or on land that should not be used for residential or commercial expansion (the marsh lands of southern Louisiana come to mind).

Jerome-Jean Haegeli, chief economist for the world’s largest reinsurance company Swiss Re, says, “We cannot quantify the exact effects climate change has on weather-related catastrophes, but it is clear that climate change is a systemic risk to the global macroeconomy.”

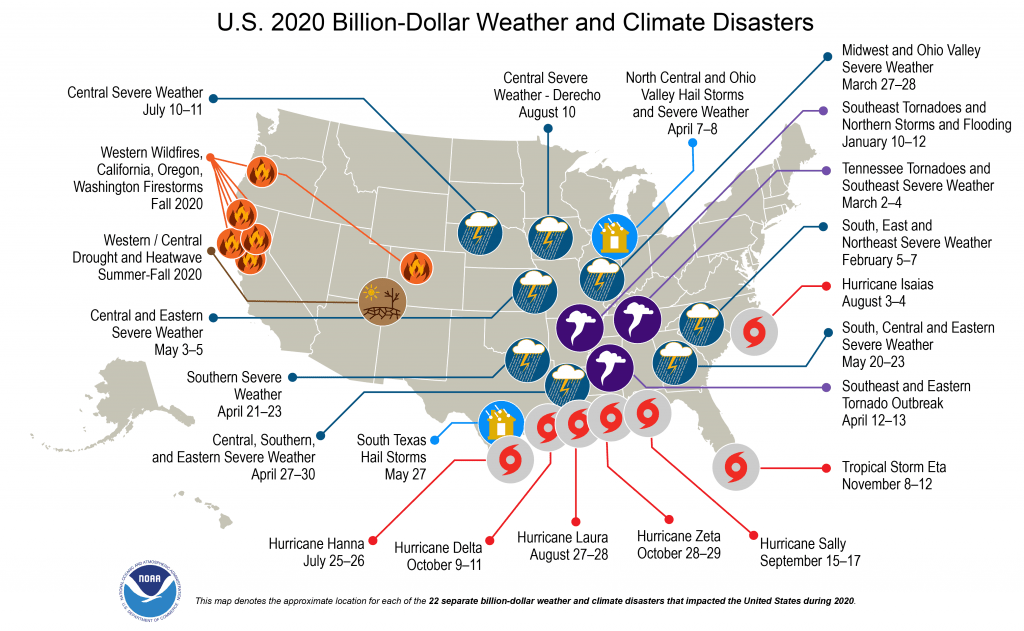

Most of the community and government preparedness focus is on primary perils—the big natural disasters such as hurricanes, wildfires, etc. There was extensive media coverage of the record number of hurricanes in 2020, for example. But more often, it is random thunderstorms or wind events, often unnamed, that cause the most damage to communities. Even as someone who is a self-described “disaster junkie,” the destruction caused by these secondary perils surprises me.

More weather events mean that we need to ensure that all levels of government and community residents are ready for the impacts of both large, catastrophic, primary perils and smaller but intense secondary perils—winter storms, derechos, straight-line wind events. The response from the media, all levels of government and, to a certain extent, disaster nonprofits and philanthropy disappoints me when I see how ignored those secondary perils are.

According to Swiss Re, “Last year’s loss experience reaffirmed the significant threat presented by secondary perils. Secondary perils caused more than 70 percent of insured losses from all natural catastrophes ($81 billion) in 2020. Accumulated losses from many small- and mid-size events made it the fifth-costliest year on record in insured loss terms. The main drivers were [severe convective storms] and wildfires in the US and Australia. In all regions where extreme weather events occurred, the experience was shaped by the complex interplay of natural-world phenomena, including climate change, and socio-economic trends.”

Swiss Re reports on insured losses, but uninsured losses are often even higher. Another reinsurer, Munich Re, estimates that the total losses in 2020 were $210 billion. China had the highest individual loss—floods that cost $17 billion—but only two percent of this amount was insured. The lack of insurance is particularly impactful internationally, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Even in the United States, lack of insurance is a key issue, particularly with secondary perils. Communities in the US hit by a small storm or tornado may not qualify for FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) assistance, so recovery falls primarily to individuals, nonprofits, philanthropy, and local and state governments.

Meanwhile, the global climate crisis is leading to a growing number of disasters year over year. The National Centers for Environmental Information at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) track the number and costs of weather and climate related disasters. They found that, “the 1980–2020 annual average is 7.1 events (CPI-adjusted); the annual average for the most recent five years (2016–2020) is 16.2 events (CPI-adjusted).” While there were seven named tropical events in 2020, the rest have names such as “western wildfires,” “severe storm,” or “derecho.”

These disasters are not just occurring more frequently but are causing increased economic damage. NOAA says, “2020 sets the new annual record of 22 events—shattering the previous annual record of 16 events that occurred in 2011 and 2017. 2020 is the sixth consecutive year (2015–2020) in which 10 or more billion-dollar weather and climate disaster events have impacted the United States. Over the last 41 years (1980-2020), the years with 10 or more separate billion-dollar disaster events include 1998, 2008, 2011–2013, and 2015–2020.”

Most US disaster response groups are funded by philanthropic donations from individuals, private foundations, corporations, and other giving programs. They rely heavily on volunteer labor to keep their operations going. But immediate response is expensive. This is particularly true when the event occurs in a large urban center where pre-existing conditions have already left large sections of a community facing marginalization. And even when disasters occur in a small community or area, they receive fewer resources from government or philanthropy. There is a dearth of media attention and, as a result, outside assistance from national disaster response organizations is also far lower.

No matter the size of the disaster, attention and focus fades quickly, as media, national groups, and funders move on to the next big event. The lack of media attention inhibits recovery fundraising. Volunteers have used up their time off or are needed back at home. In all cases, communities are left on their own to rebuild and recover, which often takes years.

Underfunding Disaster Response and Recovery

Charitable donations tend to come in quickly to communities immediately after a disaster but slow down to a mere trickle after a few days, and philanthropic support typically stops altogether after six months. Some government programs—such as FEMA—provide immediate funds, but others don’t release financial support until two or more years later (e.g., the US Dept. of Housing and Urban Development).

Even when funds are released quickly, they’re insufficient to address the need. For example, FEMA’s maximum grant allocation or “max grant” for 2020–2021 was “$36,000 for housing assistance and $36,000 for other needs assistance.” Yet, max grants are rare. A myriad of regulations, complicated paperwork, and private insurance rules result in people getting much less. A 2016 analysis of a dozen high-profile disasters saw average payouts of $8,000 or less.

The Advocate reported, “Superstorm Sandy, Hurricane Katrina and the San Diego wildfires all saw average payouts of between $7,000 and $8,000, while grants after the March floods in Louisiana and Texas averaged in the $5,000 range. The average payout for those affected by Hurricanes Rita, Isaac, and Gustav was about $3,000, according to data provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.”

There is a general lack of financial support for disaster recovery, but research shows that people who identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) fare the worst. BIPOC communities are getting poorer after disasters, while white communities are getting wealthier. Even FEMA’s own National Advisory Council issued a report that rebuked the organization for its failure to address systemic racial discrimination that led to the post-disaster loss of wealth in BIPOC communities.

There is even less support for preparedness and mitigation. And again, it is BIPOC communities and people living in poverty that suffer because they most often live in physically hazardous neighborhoods due to redlining, discrimination, and the location of the cheapest housing stock.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Collectively, we are failing to help communities, families, and individuals recover to their full potential. Disaster recovery takes years, and for some people, it never happens.

At CDP, we encourage philanthropy to make more effective disaster grants based on equity and focused on long-term recovery. It is often a hard message to get out because of the visual focus and attention to the immediate response phase. We have long said, “All funders are disaster funders,” and COVID-19 has actualized that motto for many in philanthropy. However, even in pandemic grantmaking, the focus is on the immediacy of needs. Recovery from COVID-19 will take years, and funders need to think about intentionally supporting equitable recovery.

Our 2020 report, Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy, tracked $468 million in institutional philanthropy from US foundations, public charities, and non-US donors in response to 2018 disasters worldwide. It showed that 50 percent of the dollars and 55 percent of the transactions were for response and relief. Reconstruction and recovery received 12 percent of the dollars. Funding for preparedness, resilience, risk reduction, and mitigation activities combined obtained just six percent of grant funds.

When you add in donor-advised funds, corporate giving, and online giving, the amount given rises to $1.2 billion. US households contribute approximately $3 billion to the pot. While $4.2 billion sounds like a lot of philanthropic giving (and it is), it pales next to government spending, which we tracked at almost $72 billion in 2018. But even this is not enough to bring communities back to their pre-disaster state, let alone improve their conditions to help prevent further harm.

Although it’s critical to attend to immediate individual and community needs after a disaster, the problems in the system will not be improved by only looking at now. We need to look at what to do before disasters strike and how to help communities recover afterward better.

Our Funding Approach Needs to Change

How do we solve for chronic underfunding amid growing need? We don’t need to look much further than the response to the pandemic to show what is possible.

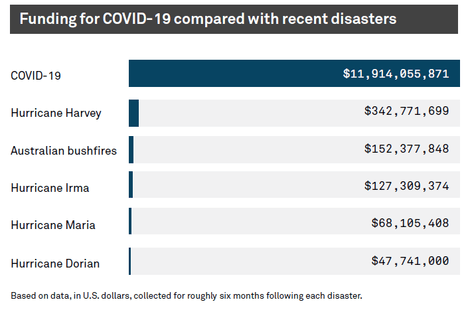

In 2018, contributions from philanthropy, individual donors and global governments combined totaled $76 billion. In 2020, with philanthropy alone, Candid and CDP have already tracked 45,397 COVID-19 donations worth $23.4 billion (USD) as of May 27 ($20.2 billion by the end of 2020).

This does not include government funding, which in the US alone is well over $5 trillion (not including $3.2 trillion in Federal Reserve support); indeed, if all money authorized for COVID-19 is ultimately disbursed, the cost of the total federal response ultimately could exceed $12 trillion. With a global pandemic that shows no sign of stopping for at least another year or more, plus the funds needed for recovery, even these figures may rise.

What COVID-19 has shown us is that when there is political will, the money is there. In 2020, everyone dug a little deeper. When you look at the chart above, it is evident how disaster giving pales in comparison to COVID-19 giving. Even with the Ebola crisis in 2014, philanthropy provided only $363 million in the first six months, compared to $11.9 billion for COVID.

As I have said on many pandemic-themed webinars, “This is the rainy day you’ve been saving for.”

With many households suffering from loss of income(s), we saw an increase in reuse groups, bartering, and mutual aid. While incredibly helpful, this is not sufficient for disasters in the future. Institutional philanthropy has stepped up, but governments and high wealth donors must do the same. And philanthropy needs to continue its spending. There is an immense amount of money being held in donor-advised funds: $141.95 billion in 2019. Imagine if instead of holding funds in a DAF for future generations, this money was used to help fund the full life cycle of disasters. Additionally, governments need to continue to spend on future disasters like they have on COVID-19. While the numbers spent on COVID-19 response have been impressive, there will be post-pandemic recovery needs for years to come.

Our Funding Structures Must Change, Too

But while CDP certainly doesn’t have all the answers, I also know money itself isn’t the only solution. Structural funding changes need to be incorporated into pandemic recovery and to confront the increasing natural hazards we will continue to face.

FEMA provides emergency response assistance, while other federal agencies such as the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Economic Development Assistance (EDA) provide recovery support. But the work and funding aren’t well coordinated. Additionally, disaster funding is almost always reactive, not proactive. Perhaps not surprisingly, governments (at any level) don’t actually know how much money they spend on disasters because every department and each level of government tracks its allotments differently.

Our colleagues at Pew Charitable Trusts have recommended a centralized way to monitor, track, and fund disasters that is the responsibility of a core department. This would allow all governments to plan and allocate funds into their budgets ahead of time, rather than just responding in an emergency.

Mitigation spending, if political inertia is overcome, can reduce the amount needed for response and recovery. A 2018 study by the National Institute of Building Sciences found that for every $1 invested into mitigation, governments can save $6 in disaster costs later. With riverbank flooding, the savings were $7 per dollar spent.

CDP promotes prioritizing local knowledge and leadership so that mitigation and recovery activities reflect local needs. Planning should include those most affected by disasters; their experience living in a disaster zone likely includes strategies for fixing the problems.

We need to improve the speed in responding to large, low-attention disasters, and increase spending on preparedness and mitigation efforts. We need to make long-term investments in community recovery.

Most importantly, however, all funders collectively need to invest in addressing the root causes of marginalization, especially those affecting BIPOC communities, that lead to increased risk of negative outcomes after a disaster.

It is within our ability to effect a change in disaster recovery, to reduce their impact, and center equity in our responses. But doing so will require coordination and a willingness to share the wealth while doing things differently.