Deaths, Near Deaths, and Reincarnations: Part 3 of 5

Editors’ note: This article is featured in NPQ’s new, winter 2014 edition, “Births and Deaths in the Nonprofit Sector.” This is the third part of NPQ‘s mini–case studies on the death, near death, or reincarnation of five organizations. Make sure to read part 1 and part 2 here.

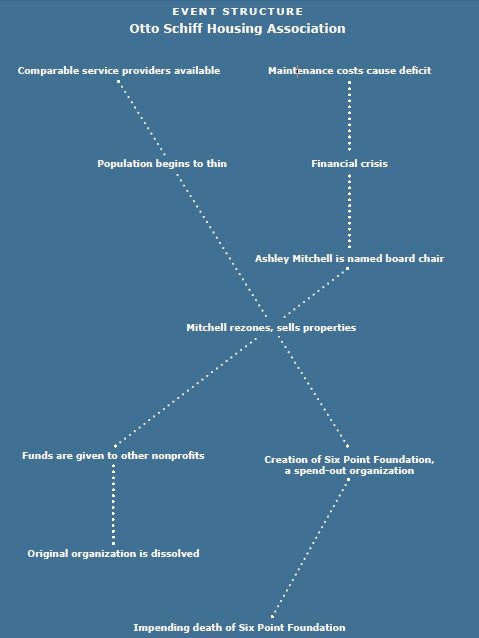

This article examines the closure of the Otto Schiff Housing Association (OSHA), a nonprofit organization located in London that serves survivors of the Holocaust and their families residing in the United Kingdom. In 2001, after more than twenty-five years of service, board chair Ashley Mitchell determined that the best way to serve OSHA’s clients and have a greater impact on available social services would be to liquidate all of the organization’s assets and distribute the money to other nonprofits that also serve Holocaust survivors and Jewish refugees. In addition to distributing its funds to other agencies, the Otto Schiff Housing Association transformed into the Six Point Foundation, a grant-making organization that provides financial assistance to that same population.

Many nonprofits hope that their respective efficacies will put them out of business—by serving the client population fully, there would no longer be a need for such service in the future (in other words, mission accomplished). In the case of OSHA, however, Mitchell concluded that Holocaust survivors would be better served by other nonprofits in the area. And, with respect to its new foundation, as a spend-out organization Six Point plans to close in fewer than three years, when all the funds have been used.

Establishment of the Otto Schiff Housing Association

In 1933, a group of community leaders created the Central British Fund for German Jewry (CBF), presently known as World Jewish Relief (WJR), with the mission of aiding Jewish refugees. The organization played an important role before, during, and after World War II, assisting German Jews in emigrating before the start of the war, providing housing at a camp for German Jews who were at risk of being deported during the war, and helping Holocaust survivors and their families reclaim their properties and rebuild their lives afterward. According to a press statement issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) in April 1944, more than 50 percent of the thirty thousand refugees from Germany and Austria who wished to settle permanently were over the age of fifty.1

In 1955, as part of the recovery effort, CBF and AJR funded the Otto Schiff House (named after one of the founding members of CBF, who was a tireless advocate for Jews in an era of anti-Semitism)2—which housed elderly Holocaust survivors, among many other educational and supportive services.3 A brief obtained from Mitchell states that “by 1975, there were 196 refugees in residential care and 52 in sheltered accommodations”—and many more on a waiting list hoping for services.4 Programs continued until 1984, when London’s Housing Corporation decided that residential care should be separated from other services provided by CBF. As a result, in 1985 the CBF Residential Care and Housing Association was established as a separate charity and continued to care for survivors—most of whom were healthy and active sixty- to seventy-year-olds.5 In 1991, the CBF Residential Care and Housing Association was renamed the Otto Schiff Housing Association (OSHA), which managed many residential buildings, including the original Otto Schiff House.

A Decade of Decline

As the OSHA residents aged their health deteriorated, and inevitably the facilities were no longer appropriate for their needs. According to AJR’s 1989 annual report, the maintenance of the organization’s facilities wore heavily on the budget: “The facilities they provide in five homes, which include sheltered accommodation, full residential care and nursing care, can only properly fulfill their purpose if buildings and equipment are kept up to date. In an age of rapid technological and social changes this is a continuous process calling for financial support in excess of what can be diverted from ordinary income.”6 Maintaining the facilities left OSHA leaders dipping into their reserves, which were already at a deficit. In 1997, significant renovations began at the Osmond House, one of OSHA’s care homes, and construction costs quickly surpassed the budget. This restoration, combined with OSHA’s already bleak financial position, caused that year’s deficit to surpass a million pounds.7

Ashley Mitchell: Change Agent

After being a leader in Holocaust survivor services for decades and expanding its reach to five care homes and two blocks of sheltered housing sites, OSHA was losing steam.8 With debt mounting, the Housing Corporation placed OSHA on its supervision list (an intervention method) out of concern for the organization’s financial troubles.9

Failure to resolve OSHA’s deficit would result in the Housing Corporation’s seizing its assets.10 Meanwhile, trouble within the organization was also brewing, and managerial issues and bad relations between trustees caused the sudden resignation of the board chair in 1998. Mitchell, a businessman and trustee at the time, was named board chair because of his experience sorting out unruly boards.11

Mitchell, who describes himself as “an entrepreneur with a very strong social conscience,” assessed the organization for two years before deciding to close the nonprofit. While the number of Holocaust survivors was declining as the years went on, maintaining the facilities to provide an appropriate level of care continued to be a difficult task. In an interview with the authors, Mitchell explained, “The level of care we were giving was excellent but you did not have to be a nuclear physicist to realize that the situation was impossible, although there was a reluctance among many people to accept this.” He believed that the cost of sustaining operations was unrealistic and that clients would be better served through other charities. Naturally, this decision came with opposition. Mitchell spoke of the resistance he received from the chief executive that ultimately led to the latter’s resignation: “I try to allow everyone to have their say but don’t put up with irrelevant political behavior. I also absolutely believe in transparency and good corporate governance.[. . .] Not everyone always needs to have the glory,” he explained. While Mitchell respected the nonprofit’s long and rich history, he felt that other charities would better serve the same population.

Maximizing Assets

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

After making the decision to liquidate and distribute all of OSHA’s assets, Mitchell’s work was still far from over. Zoning restrictions on the properties significantly decreased their market price. For the next three years, Mitchell worked with architects and lawyers to remove the zoning restrictions. While these efforts came at a hefty price of £3 million, it was well worth it in the end;12 prior to rezoning, one property was valued at £2 million and afterward was sold for £30 million.13 The other properties brought in large sums, as well. According to the Jewish Chronicle Online, “Eleanor Rathbone House in Muswell Hill was sold in 2003 for £5.7 million. Then Heinrich Stahl House in Bishops Avenue fetched £16.25 million, Leo Baeck House, another Bishops Avenue site, sold for £30.25 million, and the final property, Otto Schiff House in Hampstead, is set to realise £5 million.”14 In total, property profits raised £57 million.15 Next, Mitchell made arrangements for clients to move to other local Jewish care homes, which he described as one of the most challenging aspects of the change. “Prior evidence showed that moving people who are old and frail leads to high death rates,” he said. “We managed to move everyone in the end without any associated loss of life.”

Next, Mitchell negotiated the distribution of assets to similar organizations. As he explained, “Once I had determined that we needed to close, various charities claimed historic and moral rights to our assets. These conflicting claims, which had a vision relating to general community welfare, making a bat seem to have 20/20 vision, led to a negotiation of a tripartite legal agreement, setting out how funds should be distributed. Where money is concerned most people and organizations manage to show their worst side.”

Fund Distribution and Impact

As described earlier, after liquidating its assets, OSHA distributed its remaining funds to several related organizations that serve members of the Jewish community. Most notably, close to £20 million was granted to Jewish Care, which created a nursing and dementia care facility also bearing Otto Schiff’s name, and £16 million to WJR.16 OSHA also distributed funds to AJR, Jewish Community Housing Association, and Jewish Blind and Disabled, which received more than £500,000 each,17 and money was granted to Jewish residential and nursing care programs, the Holocaust Centre, and a local Jewish center, too. According to Mitchell, thousands of people have benefited as a result of distributing OSHA’s profits. “Looking at some of the capital projects which we have helped to fund, I have no doubt that we could not have done these ourselves [nor could have] the organizations that we have helped and done a better job,” he said.

Creation of the Six Point Foundation

Additionally, £4.09 million created the Six Point Foundation.18 Named after the six points on the Star of David as well as the six million Jewish people killed during the Holocaust, the foundation offers two types of grants: individual grants and organizational grants. Individual grants are awarded to Holocaust survivors living in the United Kingdom for services that will enhance the quality of their lives. Individuals must go through a partner agency that requests the Six Point Foundation grant on their behalf. Many of these grants are small but meaningful. Examples include new computers, walk-in bathtubs, and travel expenses to visit family in the United States.19 These grants help support and better the lives of the people that OSHA once served. Short-term organizational grants are awarded to nonprofits in the United Kingdom that serve elderly Jewish people, to help support programs for Holocaust survivors. Organizational grants have been awarded to purchase a bus to transport elderly to social gatherings, operational costs to supply kosher meals to the elderly, and programming costs for a religious study group.20 Six Point describes itself as a spend-out, grantmaking foundation, meaning that it plans to close once it distributes all of its funds. Because of the foundation’s spend-out model, these grants are not intended to be recurring.

Since the Six Point Foundation’s establishment, it has received additional financial support from OSHA. As reported in the foundation’s 2013–14 financial statements, OSHA granted the foundation £1.675 million and an additional £1.2 million for a specific technology initiative.21 Additional funding is not guaranteed in the future, according to the foundation’s executive director Susan Cohen. This “bonus” funding was a result of the resolution of potential liabilities. OSHA previously earmarked funds for contingencies, such as pension liability for former employees, that have since been resolved and deemed unnecessary. Since OSHA no longer needs to hold these funds in reserve, it distributed them to the foundation.

Currently, the Six Point Foundation expects to cease its operations in March 2017. The foundation’s financial statements corroborate its trustees’ views on the spend-out model. According to Cohen, “Trustees reconfirmed their position that they did not wish to be held to a strict spend-down timeline but recognise, given the needs of the Foundation’s target group, that a further three to four years is a realistic timeframe.”22

Current State of the Otto Schiff Housing Association

While OSHA is no longer a direct-care provider, the organization still exists. OSHA’s 2013 financial statements show that it is still moving hundreds of thousands of pounds and earning interest from its investments. Because of OSHA’s responsibility to two regulatory agencies, the Charity Commission and the Housing Corporation, the organization has had legal issues when trying to merge the last of its assets with another charity.23

The organization has settled other major obligations, such as pension funds, but major obstacles remain. According to Mitchell, OSHA is “obliged to repay certain Social Housing Grants to the relevant government bodies. These can only be undertaken once an invoice has been raised by the [Housing Corporation]. However, obtaining this document has been equal to sucking blood from a stone.” Once this invoice is produced, OSHA will use its remaining funds to meet this obligation, in addition to covering other operating expenses such as annual audit costs and legal fees related to the closure. As Mitchell explained, while he hopes to have everything finalized by March 2015, “if it continues to be difficult to get this done, I will recommend to our trustees that we just close up.”

• • •

The Otto Schiff Housing Association has a rich history in the United Kingdom’s Jewish refugee community, and remains committed to providing care to hundreds of Holocaust survivors and Jewish refugees, even if it is no longer providing direct-care services. Thanks to the guidance and determination of Ashley Mitchell, the Otto Schiff Housing Association turned financial deterioration into an opportunity to provide major financial support to other Jewish care providers working with the same client population, or directly to individuals through the Six Point Foundation. As Mitchell settles the organization’s remaining financial obligations, the history of the Otto Schiff Housing Association is a powerful example of an organization’s dedication to its mission.

Notes

- Ronald Stent, “Jewish Refugee Organisations,” in Second Chance: Two Centuries of German-Speaking Jews in the United Kingdom, Werner E. Mosse et al, eds. (Tübingen, Germany: J. C. B. Mohr, 1991), 597.

- See Anthony Grenville, “Otto Schiff: In Defence,” AJR Journal 14, no. 6 (June 2014), 1–2.

- Stent, “Jewish Refugee Organisations,” 598.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time,” courtesy of Ashley Mitchell.

- Ibid.

- “The AJR in 1988: A Hive of Activity,” AJR Information 44, no. 5 (May 1989), 1.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- Kaye Wiggins, “Ashley Mitchell, Chair of the Otto Schiff Housing Association,” Third Sector, March 15, 2011, www.thirdsector.co.uk/ashley-mitchell-chair-otto-schiff-housing-association/governance/article/1059518 cde3.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- “How to Make £57 million in Sales,” Jewish Chronicle Online, March 3, 2011, accessed November 3, 2014, www.thejc.com/community/community-life/46105/how-make-%C2%A357-million-sales.

- This and all subsequent unreferenced quotes by Ashley Mitchell are from an interview with the authors.

- Wiggins, “Ashley Mitchell, Chair of the Otto Schiff Housing Association.”

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- “How to Make £57 million in Sales.”

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- “UK Holocaust Charity in Sunset,” eJewish Philanthropy, March 1, 2011, accessed November 3, 2014, ejewishphilanthropy.com/uk-holocaust-charity-in-sunset/.

- “How to Make £57 million in Sales.”

- Six Point Foundation (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Report and Financial Statements for the Period 21 July 2011 to 31 March 2012, 2, accessed December 9, 2014, www.sixpointfoundation.org.uk/domains/sixpointfoundation.org.uk/local/media/downloads/six_point_foundation_trustees_annual _report_and_accounts_2011-12.pdf.

- Ibid.

- “Case Studies,” Six Point Foundation, accessed November 3, 2014, www.sixpointfoundation.org.uk/case-studies.

- Six Point Foundation (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 March 2014, 5, accessed November 4, 2014, www.sixpointfoundation.org.uk/domains/sixpointfoundation.org.uk/local/media/downloads/six_point_foundation_trustees_annual_report_and _accounts_2013-14.pdf.

- In an interview with Susan Cohen.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

Katie Grivna is a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Sandi Toben is Host Sub-Committee Chair at the Spruce Foundation, Philadelphia, and a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania.