July 31, 2019; The Atlantic

Writing in the Atlantic, Maura Cheeks, who grew up in a Black upper-middle-class family, draws on her personal history to “better understand the intricate narratives that make wealth in the Black community so complex.” Cheeks acknowledges her privilege—her grandfather developed a business and her father was a professional basketball star—and yet, Cheeks notes, the obstacles to building wealth in communities of color are often daunting.

Take the GI bill, passed in 1944. By 1956, nearly 10 million veterans had benefitted from its provisions that heavily subsidized college and vocational education. In her family, Cheeks writes that her father’s father, aunt, and uncles were World War II veterans. Four relatives who were veterans got government jobs, but they didn’t end up in college. One reason: Even though 49 percent of Black veterans (compared with 43 percent of white veterans) took advantage of some sort of education or training offered through the GI Bill in the first five years after World War II concluded, most “ended up pursuing vocational training, as counselors who approved the benefits steered blacks into low-paying jobs or historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).” And getting into HBCUs in the postwar period was not easy: “Short on space, they were forced to turn away up to 50,000 Black veterans,” Cheeks notes.

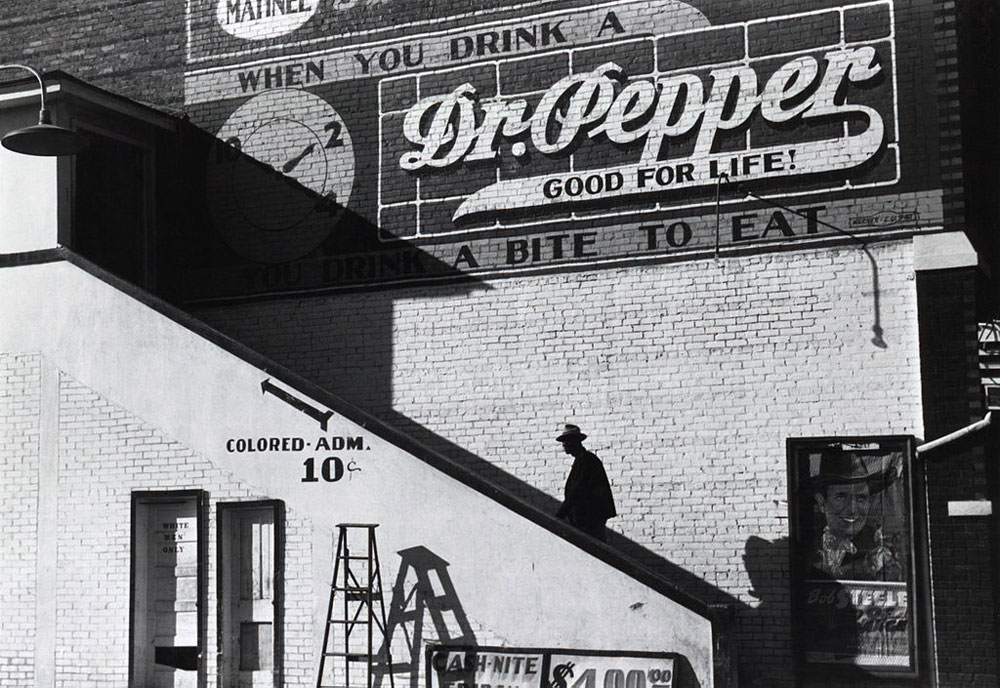

Then there are the dynamics of the housing market, rooted in redlining, a practice that from the 1930s through the 1960s—and even beyond—routinely deprived people of color of loans to buy homes. “One cannot talk about closing the wealth gap in any meaningful way without acknowledging that middle- and upper-class black families have lost and are still losing wealth because African Americans were ushered into segregated neighborhoods and denied the same benefits extended to white Americans,” Cheeks explains.

Even when you make it, the need to support extended family, many of whom may be in poverty, can restrict wealth building. Maura’s father was Maurice—the National Basketball Association (NBA) star, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame last year. Professional salaries when Maurice played weren’t as high as they are now, however; in his rookie season in 1978, Maurice Cheeks earned $30,000 ($123,000 in present-day dollars). Today, by contrast, the minimum salary for a rookie in the NBA is slightly over $838,000.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Moreover, Cheeks notes, “As soon as my dad started earning a salary, he sent much of it back to my grandmother, who continued living in the Robert Taylor Homes [public housing] when he first started playing in the NBA. This, Cheeks adds, is not unusual. Citing the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), the world’s longest-running longitudinal household survey, it turns out that 36 percent of middle-income Black families’ parents lived in poverty, compared with eight percent of middle-income white families’ parents. Moreover, Cheeks adds that PSID data show that “parents of middle-income Black families were more than eight times as likely to face poverty as the parents of middle-income white families.”

These numbers, as NPQ has noted before, alter how much Black students need to borrow to attend college. “Howard graduates more African American students who go on to pursue science and engineering doctorates than Harvard, MIT, and Yale combined,” Cheeks points out, yet historically black college and university (HBCU) graduates “have a median debt that’s more than 30 percent higher than that of graduates at other public and nonprofit four-year schools.” Cheeks adds that, “Parents of HBCU students borrowed an average of roughly $14,000 in federal student loans to help pay for the 2017–18 academic year.”

Cheeks lauds the proposals for wealth taxes that are being advanced by Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and others, but she cautions that such measures address symptoms of wealth inequality, not the causes. Recalling the origin story of Silicon Valley of companies like Apple being created out of garages, Cheeks asks, “Would companies like that exist if failure meant living in the projects instead of a middle-class garage?”

Cheeks adds, “What we need is a formal reconciliation with the way wealth is built and maintained. To put the freedom of choice created through wealth back into the hands of the people who have had that freedom denied to them for far too long.”

Cheeks concludes, “The right to pursue a passion and build wealth seems to be reserved for a select few. Maybe no one has the right to do both. But you’re less likely to have to choose if the generations that came before you were wealthy, and less likely still if that generation was white. Closing the wealth gap sounds like an abstract policy agenda, but it’s really about giving more people the power to choose how to care for themselves and their families.”—Steve Dubb