July 18, 2018; Education Week and Brookings Institution

The federal government addresses the needs of our nation’s children through more than 80 separate tax provisions and allocations to support specific programmatic efforts. Through direct support, the federal government provides about 35 percent ($375 billion in 2017) of all governmental funding focused on the health and welfare of children through age 19. For nonprofit organizations whose mission touches on the lives of youth, a recent projection that the tax and budget policies of the current administration will reduce this share adds a new worry to their agenda.

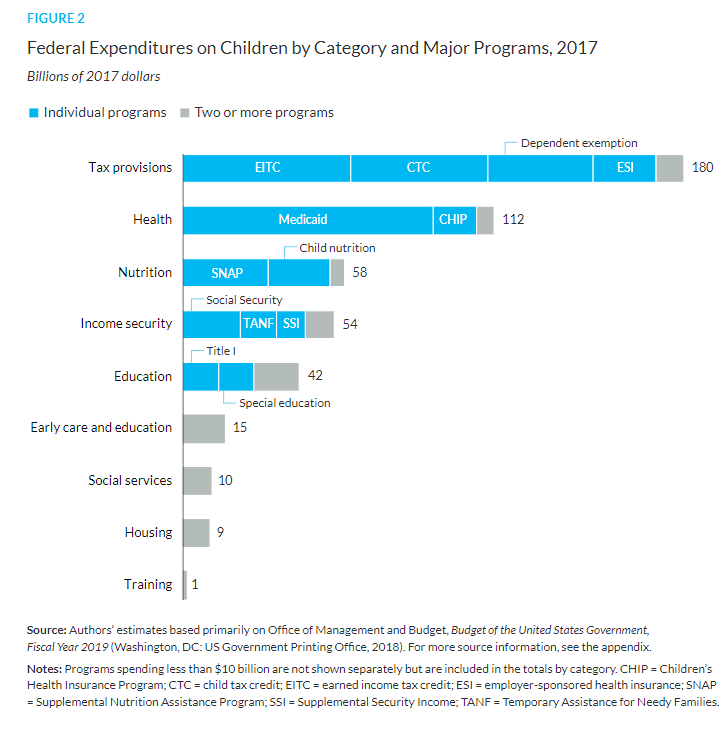

The Urban Institute’s study, “Kids’ Share 2018,” factored in a broad range of federal funding streams, ranging from direct cash support like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) to programming funding directed at poverty, health, education, housing, and social services. Over the next decade, every major category of spending on children (health, education, income security, and so on) is projected to decline relative to GDP.

According to Education Week’s read on the study, federal children’s funding will “drop from 9.4 percent of the fiscal 2017 budget to 6.9 percent after 10 years, a decline of 27 percent from 2017 levels…spending on elementary and secondary education to dip to $37 billion from $42 billion, and for early-childhood education to drop to $14 billion from $15 billion, after adjusting for inflation. However, the organization also predicts spending on children’s health and income security is expected to rise somewhat in the coming years.”

The Urban Institute also noted an important change in the mix of how federal support is directed at children: Direct cash support to children has decreased and allocations to specific programs have increased. “In 1960, cash payments and tax reductions were the main form of support for families with children. Since then, spending on in-kind benefits and services has grown and now accounts for more than half of all expenditures on children.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Urban Institute’s findings do not reflect some growing bias against children. They are the unintentional outcome of policies put in place to control the deficit by limiting how the overall federal budget could grow. With a large, ongoing commitment to defense, the cost of financing a growing federal debt, and the unyielding Social Security and Medicare needs of the baby boom cohort, current tax and budget policy leaves little space for new child-focused spending at the federal level.

Cary Lou, a research assistant at the Urban Institute, told Ed Week “most other children’s programs, including education, they don’t increase with more children or more need automatically…without tax increases or changes to other parts of the budget. There really is a squeeze in the budget on children’s spending, but also things like defense and other discretionary and mandatory programs for adults outside of the entitlements.” Specifically, “federal expenditures on children—discretionary spending, mandatory spending, and tax provisions—are projected to decline as a share of the economy when comparing 2017 to 2028. Over the next two years, however, expenditures on tax provisions are expected to increase, and discretionary spending falls only slightly relative to GDP because of recently enacted legislation.”

The Institute’s study is no guarantee; over a decade, many things can and will change. Elections may flip control of the White House or Congress. The economy may continue to grow, or it may fall into the next recession. These and many more forces can make funding levels change. Yet, the concern should be enough to prompt organizations to factor them in to their ongoing planning looking forward. A decrease in direct cash supports that flow to parents for children through such programs as the Earned Income Tax Credit may increase a range of service needs at the grassroots level. Direct program allocations reach their endpoint through varied mechanisms that may involve state and local governments before they end at the organizational level. Knowing where these channels touch an organization will make planning for possible reductions easier.

The Urban Institute’s budget forecast report is also a call for increased advocacy for the needs of children. Changing federal policy to at least maintain support levels for important services to children is one goal advocates may wish to consider. Alerting state and local officials to potential new challenges is another.

A just-published Brookings Institution study of the capacity of cities to increase their revenues and the varied constraints placed on them by state governments provides new data to guide local lobbying efforts. Brookings concludes:

If cities are to successfully design, fund, and implement policies that provide high-quality educational opportunities, safe streets and neighborhoods, modern transportation networks, affordable housing options, and economic opportunities for all residents, they will need significant fiscal resources and flexibility. This imperative is particularly salient in an era of federal devolution of power and responsibility. Ultimately, expanding the fiscal policy space of cities will serve to increase economic growth, prosperity, and inclusion for the nation as a whole…

This speaks directly to the hurdles before advocates for the needs of children and the health of communities, not to mention the future of us all.—Martin Levine