November 13, 2020; Washington Post

When the Washington Ballet had to put its programs on pause this spring, artistic director Julie Kent, an accomplished former ballerina herself, knew that keeping her company of 40-plus dancers dormant indefinitely was a non-option.

“You can’t just stop,” Kent explains to Thomas Floyd of the Washington Post. “A dancer’s life already requires such incredible devotion and commitment at a very young age. To ask a dancer to take a year off or not continue to dance is crushing. Our body is our instrument, and you can’t just leave it alone. Otherwise, you never get it back.”

The financial impact of the pandemic for the nonprofit ballet has been significant. According to spokesman Scott Greenberg, pandemic-related financial setbacks shrank the ballet’s annual budget from about $15 million to $9 million, an unsurprising outcome given that it could not host shows; past Form 990 filings show that the nonprofit has typically relied on ticket sales for over 60 percent of its annual income.

The ballet company knew that a fully digital 2020–21 season was likely, but it would require multiple adjustments for the nonprofit to pull off. One step was to enter into an alliance with Marquee TV, becoming in the process “the international arts-streaming platform’s first partnership with a US ballet company,” according to Floyd.

As Floyd details:

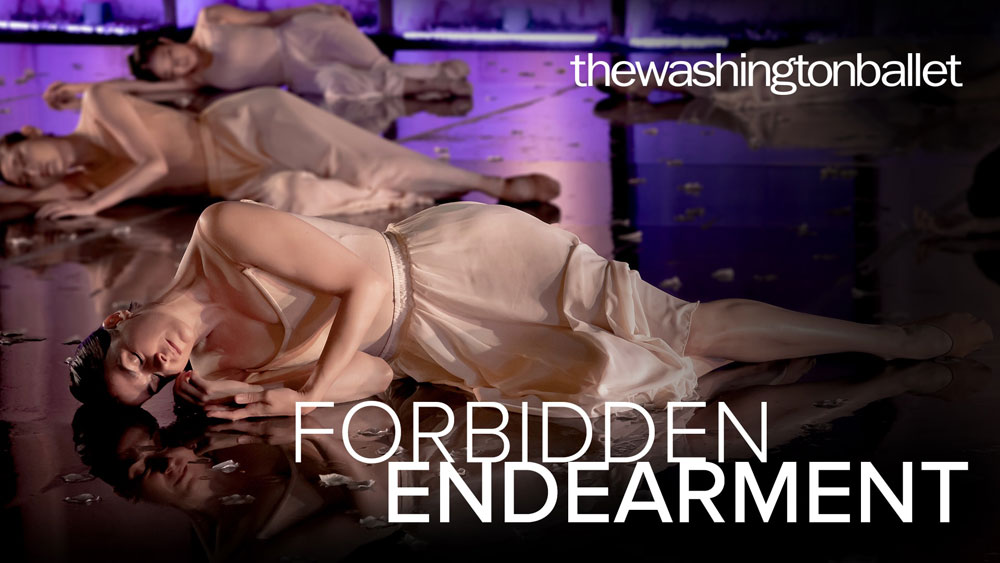

The cornerstone of that collaboration is an initiative called “Create in Place,” featuring four newly commissioned works, recently performed and filmed by the Washington Ballet under health and safety protocols. Last month, the first two “Create in Place” performances—“Chronos,” choreographed by Xiomara Reyes, and “Forbidden Endearment,” by Tamás Krizsa—began streaming on Marquee TV. In January, the subscription service will release Helga Paris-Morales’s “Womb of Heaven” and Andile Ndlovu’s “Something Human.”

But the partnership with the streaming service was only one piece to the puzzle; in fact, it might have been the easiest piece. The question remained as to how to develop a ballet production safely amid the novel coronavirus. The solution centered on a concept with which many parents with school-aged children will be familiar—pods.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As Floyd details, “To execute its ‘Create in Place’ vision, the company split its dancers into four 10-person ‘pods,’ each assigned to one production. Every dancer had to test negative…before starting rehearsal and again before filming. The performers wore masks during the weeks of rehearsals, and they used an app to regularly log their temperature and other medical information.”

Kent explains that, “Dancers are, by nature, disciplined, committed and take their art very seriously, and they see that there are not many companies that are back in the studio dancing.…Dancing in a mask and the restraints of the protocol, I mean, nobody loves it. But in comparison to not dancing, really, it’s nothing. It’s what you have to do in order to keep going.”

It wasn’t just the dancers who had to adjust. A US composer, Blake Neely, who wrote the music for “Forbidden Endearment,” one of the four shows, used Zoom to sit in on a recording session with the Budapest Art Orchestra, contribute feedback, and deliver that original score. Choreographers had to design their routines so that the only dancers touching each other were those who live together as roommates or partners. Distancing made rehearsals tricky, since only five dancers at a time were permitted to be in the studio.

After the rehearsals, the performances were recorded outdoors in nearby suburban Maryland. Two of the shows, “Chronos” and “Forbidden Endearment,” were performed at the Washington Ballet’s storage warehouse in Landover. “Something Human” was recorded at the Patapsco Female Institute in Ellicott City, and “Womb of Heaven” at Wheaton Regional Park.

Floyd writes, “It wasn’t until the cameras were rolling that the performers removed their masks, all 10 dancers stepped onstage, and the full choreography played out as envisioned for the first time.” As Kent relates to Floyd, “Part of what we do as performers is, we deliver when the time comes. When the curtain goes up, you have to bring it.”

As for the themes, certain through-lines that are relevant to 2020—grief, isolation, and the human experience—can be found within the four productions.

“It’s really important to me that this moment in time is captured, and that it’s understood that these works were produced under incredible duress,” says Kent. She adds, “this is sort of a testament to the human spirit. We will continue, and we are forging the path forward, even under very challenging circumstances.”

Kent doesn’t know what comes next, but she expects the partnerships developed to be a part of the ballet’s future in some form, even after the pandemic ends. She observes, “It’s been made abundantly clear that for performing arts to survive we need to be expanding our own ideas.”—Steve Dubb