At NPQ, we seek to foster an “active democracy whose values are fully grounded in human rights, economic and social justice, racial equity, and thriving communities.” Back in 2003, Minnesota Council of Nonprofits director Jon Pratt began an NPQ article by noting that “Democratic decision-making is inevitably messy, so it requires us to develop systems to help manage our dialogues.” But how can people use an “inevitably messy” process to achieve common goals?

The answer is complicated, and we often fall short. But sometimes we succeed. And in recent decades, a range of strategies has emerged to more effectively make group decisions. Back in 2007, a 68-chapter volume profiled dozens of approaches.

Here I focus on one such method, known as Future Search, which has been used across the world. Back in 2001, Sandra Janoff and Marvin Weisbord, who co-created the methodology, touted some examples, noting in NPQ that:

- “In southern Sudan, adults from many sectors, including the army, met with child soldiers to plan how the youngsters might be reintegrated back into community life.”

- “In Hawaii, a whole community of seven towns took on the question of how to preserve their cultural heritage and reverse trends of declining health and increasing alienation in the institutions that affect them.”

- “In Worcester, Massachusetts, a community group brought together residents, board members, funders, and other partners to figure out how to refocus on developing lifelong relationships with families in the area.”

Out of these gatherings came impressive achievements—and there are many, many others. As Peggy Holman, an editor of that 68-chapter volume, explains, “One of the most hopeful and under-reported phenomena is of people doing conversations in communities for people to bring agency and a shared sense of possibility—the ability to address the gnarly problems that all of our communities are facing.”

Richard Lent, a facilitator and author on meeting-design strategies, concurs. As Lent explains, “Until the 1950s or 1960s, we didn’t know much about how groups work.… In the 1980s and 1990s, some of these principles bubble out into a family of methods. They may look different (open space, Future Search, appreciative inquiry, I could go on). What they are is the next generation of meeting technologies. The last was Robert’s Rules. A good meeting was one that was ordered. Later we learned that a good meeting is when you get to hear from the multiple points of view, the different knowledge that is in the room to get to a decision that all will support.”

Future Search, as Lent mentions, has been employed across the world for a wide range of topics—conflict resolution, education, health, community economic development, and environmental justice, among them—and in many contexts, with conveners including governments, nonprofits, religious groups, and for-profit firms.

And yet we know that even as our capacity to address collective challenges grows, so too do our many social problems, such as structural racism, climate change, economic inequality, and the current novel coronavirus pandemic.

“Why are we falling further behind? We’re in a complex, Einsteinian world, and we’re dealing with it in a Newtonian way,” Holman observes. There is, in short, an under-appreciation of increased social complexity, and, she adds, a “lost sense of us.”

Newtonian Decision-Making: The Deceptive Simplicity of Robert’s Rules

It’s worth noting that when Pratt was writing about the messiness of democratic decision-making, he was referring to Robert’s Rules.

The Robert of Robert’s Rules of Order is US Civil War General Henry Martyn Robert. Robert published his first “rulebook” back in 1876, and refined it in the 1890s when his method gained widespread acceptance. One wonders what former British Speaker John Barcow—famous for his shouts of “Order!”—would’ve done without it. For those so inclined, a 12th edition is scheduled to be released this fall, with new provisions for electronic meetings.

But while Robert’s Rules has many shortcomings, how do we get beyond it? Of course, one alternative is consensus decision-making, used for centuries by Western (notably the Quakers) and indigenous groups (notably the Iroquois). There are also systems that apply elements of consensus approaches in organizational decisions, such as sociocracy.

But while consensus and Robert’s Rules are often posed as opposites, they share an important characteristic—namely, they are both social technologies typically used to advance short-term group decisions. Anyone who has ever participated in nonprofit strategic planning, to pick one example, knows that there’s more to it than voting rules.

The bad news is that meetings, regardless of whether you go the consensus or Robert’s Rules path (or the various options in between), hide many more decisions than they make. The iceberg is not a bad analogy. Far more of the iceberg remains below the water line than above. Who controls the agenda, and decides what to decide matters a lot.

The good news is that newer strategies address this challenge. Typically, these approaches involving bringing people together under one roof—a method that is challenging during these days of physical distancing, although virtual workarounds are rapidly being developed.

A key insight that informs many of these, to quote the late Yogi Berra, is that “You can observe a lot just by watching.” And by looking at the iceberg below the waterline, sometimes major breakthroughs can occur.

Lifting Up the Iceberg: Making Visible Hidden Decisions

There are many ways to go about this discovery process. For instance, open space allows open generation of agenda items, with any community member able to lead a discussion topic, while ultimately focusing action on high-demand items. Appreciative inquiry identifies areas of success and seeks to build from those successes. World Café prioritizes small group discussions in a way that generates identifiable patterns across groups, which in turn inform larger group decisions.

As facilitator Susan Dupre notes, the strategy that will work best depends on the context. Dupre says that, in addition to facilitating Future Search processes, she’s also made use of open space, appreciative inquiry, and World Café. “I integrated all of those methodologies and designed meetings that fit particular outcomes that [clients] wanted,” she explains.

In this context, Future Search is a highly structured process, as structured as Winston Churchill’s nominally “spontaneous” remarks. As Weisbord put it a few years ago in an interview with a Hartford Business Journal reporter, “We want to control the heck out of the conditions under which people interact with one another.”

So, with Future Search, there are many specifics that must be met. One specific is there must be a central question. “The trick is to match the task with the people doing it, a job neither too big nor too small for those in the room,” note Weisbord and Janoff.

Janoff elaborates on these conditions:

What does it mean for systems to change? Here are some criteria. First of all, I use the word “leader”—or you can say sponsor. There has to be someone with an itch, who wants to put that stake in the ground and say this is something I would like to start exploring. Second: Do we have a small group of people to plan it? Third thing is the issue or the opportunity—is the issue or the opportunity potent enough for people to want to step out of their comfort zone?

The meeting is also structured, write Weisbord and Janoff, in accord with a few key principles:

- Have the right people in the room—that is, a cross section of the whole system.

- Create conditions where participants experience the whole “elephant” before acting on any part of it.

- Seek and build upon common ground.

- Take responsibility for learning and action.

The actual gathering, although size and scope can vary widely, typically consists of 60 to 80 people, and takes place over two-and-a-half days, following a carefully designed process. In a “model” Future Search, the gathering would have 64 people, drawn from eight distinct stakeholder groups—a structure that alternatively facilitates caucusing among stakeholders, and, at other times, eight separate cross-sectional groups.

A standard agenda looks something like the following:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Day 1 afternoon

Focus on the past (timeline activity, cross-stakeholder)

Focus on the present and external trends (thematic mapping, cross-stakeholder)

Day 2 morning

Stakeholder response to external trends

Focus on the present (stakeholders, identifying areas of pride and regret)

Day 2 afternoon

Ideal future scenarios (can be communicated as skits, cross-stakeholder)

Identify common ground (value statements, entire group)

Day 3 morning

Confirm common ground

Action planning (mix of existing and voluntary small groups)

Chris Roesel, a Future Search facilitator based in Kansas, offers his view on what he finds most fundamental about the process. For Roesel, these aspects are:

- Having a diverse group reflecting key stakeholders of the system.

- Having a clear unifying purpose of coming together.

- Having some recognition of all the participants so they feel validified.

- Reviewing the past. Having people acknowledge what has happened in the past, especially around the issue, but also in the personal lives and their locale.

- Looking at the state of things in the present, what is influencing that, and what is everybody’s role maintaining or changing the current situation.

- Doing a leap out of the present into the future and dreaming about what they want in a way not restricted by the current limitations, poverty and oppression.

- Identifying where there are elements of agreement. Coming up with individual and group plans around how to achieve the areas of agreements.

One important strength of the Future Search process is that it forces the inclusion of stakeholders who too often are excluded from decision-making. But it isn’t easy.

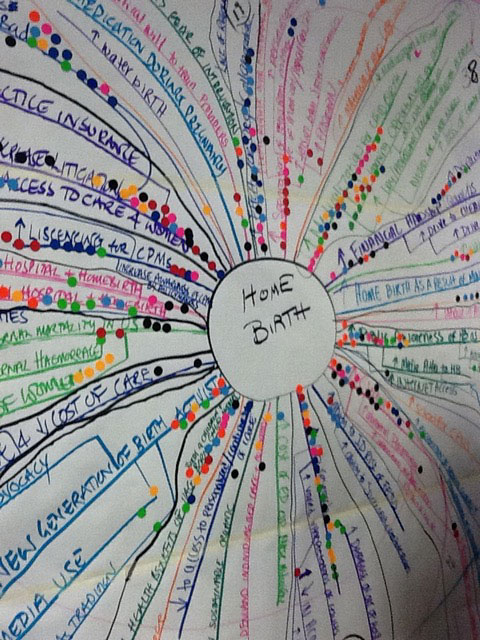

Janoff gives one example involving the issue of home birth. “Home birth was divisive,” notes Janoff. She adds, “Obstetricians were this close to creating a policy so that obstetricians could not work with midwives.” Janoff describes the gathering:

We had a summit. Boy the women who led the charge had everyone in the room. They had been so divided. You’ll see the agenda on the website. They have been doing the review meetings every couple of years. How can we work together to have ethically, medically healthy births for women, especially for women who are underserved?

Janoff adds that it is critical to include the people most directly affected in the gathering—not just nonprofit advocates. Janoff recalls a gathering that looked at assistive technology for the aging and disabled. Janoff says that at the event there were a range of disabled people in the room: “We had someone who was blind; we had someone who was physically disabled. We had people from the society for the aging.”

There was only one group missing—the intended senior beneficiaries!

“I learned from that,” Janoff relates. She adds that just like the seniors were left out of that one summit, organizers often fail to include young participants. “People will default to people who work with youth,” Janoff observes. “But that is not youth. I’ve learned from that many years ago. Make sure to say: when they are doing their stakeholder groups around youth—make sure that there actually are youth at the table.”

In the end, the results can be powerful. Janoff reflects, “What are the critical elements?” It is people coming together because they are interdependent on a task. They want to do something that they can’t do by themselves.” In Sudan, she notes, “They were literally at war. The reason they were able to take a next step was that the Future Search was not about that issue. The Future Search was about the children…it’s the task, it’s the purpose. People don’t get everything they want.”

Limits—and Can We Build Beyond?

Social technologies like Future Search can resolve many issues, but every form of decision-making has its limitations. Among the limits that Weisbord and Janoff noted years ago were that a Future Search won’t shore up ineffective leaders, it won’t reconcile value differences, and it won’t change team dynamics. (You can only create new dynamics if a new group is brought together for a new task, they add.)

As for value differences, Weisbord and Janoff write that, “When people disagree about deep-seated religious, ethical, or political beliefs that they hold sacred, a Future Search is unlikely to help them reconcile their beliefs.” Given the major value divergences evident in many countries, including the US today, this is no small concession. Weisbord and Janoff give the example of a school conference where there was no consensus on sex education policy. There could be agreement on other goals (such as parental involvement in their children’s education), but sex education was off the table. This is an important cost of the “common ground” focus of the methodology.

Yet another limitation is the dependence on a “leader” or sponsor. Some leaders are willing to identify an issue and allow for an open-ended decision-making process. Others are not. As Janoff said in an interview a decade ago, “People will say to us, ‘You should go…to these places that are in high conflict or have ethical issues or efficiency issues. You could do so much good for them.’ But that isn’t the way this works. When we are invited in, it is because there is someone in leadership that says, ‘I’m not getting what I want out of the way that I am working, and I really want to shift how I engage people in solving problems and creating futures.’”

The bottom line, of course, is while Future Search empowers voices that might usually be excluded from decision-making, it does so within the limits of the agenda-setting authority of the authorizing (sponsoring) leader and the existing power structure. The agenda-setting control of leadership might be less than in a standard setting, but it is hardly zero.

Interestingly, some of the biggest successes of the Future Search process have involved rebuilding at the end of larger conflicts, when, perhaps, a willingness to achieve common ground is more keenly felt. For instance, after the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 brought an end to 30 years of “The Troubles“ in Northern Ireland, a Future Search effort there led to an integrated development plan that “grew to include more than 1,000 farmers, educators, environmentalists, nongovernmental organizations, youth, artists, health care workers, and business people.”

One last aspect that is worth noting is where Future Search methodology works best, and that is often in indigenous communities. Janoff has a theory why. While Future Search may be of recent origin, its principles mimic far older indigenous decision-making traditions.

Janoff notes that a colleague told her once that traditional Ugandan practices would look familiar to her. As Janoff puts it, “They gather together all of the people who have to be in conversation, and they sit for two or three days together…and they are figuring out what they want to do…and when they come to a decision, when they leave, it’s binding.”

It’s an important observation. While Future Search and other related collective decision-making strategies are valuable, they work, when they work, because they are embedded in broader community cultural values.