June 19, 2015; Chicago Tribune

Summer in Chicago is a time for enjoying its glorious Lake Michigan beaches and an endless stream of music, art, and food festivals. It is also the season when drive-by shootings claim many lives and make headlines regularly. Amping up the summer celebrations and damping down the mayhem has long been a priority for the city’s leaders.

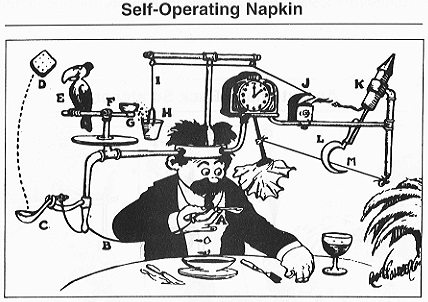

In a city whose budget is stretched to the breaking point, finding funds to support new and expanded services is more than difficult. Mayor Rahm Emanuel has seen public-private partnerships as a way to increase funding for otherwise unaffordable efforts, both for the repairing of a crumbling city infrastructure or filling gaps in the city’s social services and educational safety net.

On Sunday, the Chicago Tribune reported on the disappointing results for one of Mayor Rahm Emmanuel’s signature anti-violence programs, Get IN Chicago. Formed as a philanthropic foundation in 2013 with an initial funding goal of $50 million, according to its website, this public-private partnership sought to collaborate “with business, government, community based organizations, foundations and faith-based organizations to align and leverage existing initiatives to make Chicago safer.”

But the Tribune’s investigation found that as of “June 1st, two years into Get IN’s five-year plan, the foundation had disbursed only $3.7 million in grants to youth programs while spending $900,000 per year on its own administrative salaries and overhead, according to the most recent available records from Get IN’s fiscal agent, the Chicago Community Trust.” According to the paper, Get IN Chicago “has largely abandoned its touted plan of using the most advanced social science techniques to assess which youth programs succeed in reducing violence.”

The twin CEO co-chairs of the board of Get IN Chicago—Thomas Wilson of Allstate Insurance and James Reynolds, Jr., of Loop Capital—acknowledged to the Chicago Tribune that they had experienced “setbacks and painful lessons” as they sought new ways to deliver effective antiviolence programs to young Chicagoans. Still, they remain confident in the future of the foundation. According to Wilson, “It’s really about getting the existing system to work in a new and different way because what we know we have doesn’t work. We are trying to help bring a new set of skills and capabilities to this issue. Any time you try to do something that’s new, it’s hard.”

Beyond increasing the amount of funding available for needed violence prevention efforts, Get IN Chicago wished to use its financial heft to shape the very nature of the service system. It took on a coordinative and directing role that might otherwise have been played by the appropriate city or state agency:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- “Identify and support the expansion of proven programs to reduce violence and make the city safer.”

- “Coordinate and align these programs with existing public and community-based efforts.”

- “Monitor program implementation and measure actual performance to ensure improvements are sustainable.”

The dangers this power holds were described by Beth Gazley in a recent NPQ feature: “They include a virtual Pandora’s box of potential ripple effects, including reduced public accountability and citizen access, less donor transparency, more-challenging power dynamics, and less-stable public services.”

While the level of funding has been small, there are already indications that the foundation’s approach is raising concerns in the service community. As the Tribune reports, the paper obtained an internal memo from Evelyn Diaz, then-commissioner of the city’s Department of Family & Support Services, who served until recently on the Get IN board of directors. In this memo, Diaz claimed that Get IN “was not aligning its work with ongoing youth programs run by the city and other government agencies,” calling the results “a waste of time and effort.”

Diaz went on to suggest to the other members of the board, “We need to leverage what’s out there and what is already being paid for and organized.” But the Tribune found that at least some of the organizations Get IN had tried to collaborate with were disturbed by the nature of the relationship:

“In interviews, officials from nine nonprofit agencies criticized the way Get IN treated their organizations, with some calling its grant system disruptive to the families and youths they serve. Most spoke on condition that they not be identified because they feared upsetting the foundation’s politically connected leaders and further jeopardizing funding.”

The lack of transparency for an effort that is filling a government-like role has already been demonstrated. “We have no obligation to share detailed financial and operating statistics with people broadly as it relates to how we spend our money. That’s true of all (private) foundations,” board member Wilson told the Tribune. Reynolds added, “The dollars spent on youth programs will accelerate in the next three years, and not a penny will be left in the bank after five years. When this money’s gone, hopefully we’ll go out for more, and do it again, and grow it.”

Can the business leaders who guide Get IN Chicago learn the needed lessons from their beginning efforts and learn to collaborate more effectively? Or will we see growing tension between the vision of the boardroom and the realities of work on the streets?—Marty Levine