As I read the responses to Peter Buffett’s recent op-ed in the New York Times, I started to wonder if Buffett’s most important point was getting lost. The central problem Buffett highlights—the one that many in philanthropy are uncomfortable talking about—is that people of wealth, as Buffett puts it, “are searching for answers with their right hand to problems that others in the room have created with their left.” We’ve created a system where the individuals and companies that perpetuate environmental disasters, human rights abuses, and growing wealth inequality are empowered to direct resources intended to eliminate these problems. That so many have glossed over this point is particularly concerning because the social sector would be a lot stronger if more of us took Buffett’s comments to heart.

Major donors directing dollars intended to address problems they have created is a problem encouraged by many private and community foundations and leads to the “charitable industrial complex” that Buffett warns of, where people spend more time applying social service Band-Aids than creating systemic change. This is why, if we’re ever going to dismantle oppressive systems, those most impacted by poverty, racism, and other forms of injustice need to be the ones deciding how and where to direct philanthropic dollars.

Howard Husock writes on the Forbes site that the main problem with modern philanthropy isn’t a reluctance to fund change-oriented work, but that philanthropy is, “unfriendly to the creation of wealth that provides the resources to solve such problems.”

I’d argue the opposite: more people should be actively opposed to the accumulation and concentration of wealth, because that’s what created many of society’s problems in the first place. It’s not anti-capitalist or anti-American to see that the Great Recession tipped millions of working-class Americans into poverty or that wealth inequality is growing to dangerous levels. Even if this did result in a stronger philanthropic sector, it is not something to be celebrated. And, in reality, nonprofits are struggling to keep up with rising poverty, especially in the face of sequestration.

That said, my goal is not to condemn those who have accumulated wealth and now spend that wealth to fund social services. It is understandably difficult for those who are benefiting from the status quo to fund programs—especially advocacy and organizing—that lead to real social change and opportunities for all people, rather than just those at the top. However, I don’t think they should be the only people in the room making decisions about how to solve problems they’ve played a part in creating.

Husock goes on to say, “Not only is Buffett far too dismissive of the good that can result when the Kenyan poor have access to cellphones to facilitate commerce—he is far too pessimistic about what philanthropy, well conceived, can accomplish.”

Once again, Husock overlooks the role that unfettered capitalism has played in creating and perpetuating deep poverty in Kenya, throughout Africa, and here at home. Do we really think Shell Foundation leaders are the best people to make decisions about improving environmental health when Royal Dutch Shell creates toxic and unsafe environments worldwide? Probably not.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Phil Buchanan, writing for The Chronicle of Philanthropy, adds, “It’s unfair to issue sweeping generalizations about the motivations of individuals who [find] themselves with great fortunes.” Which is a reasonable point. There are many people with inherited wealth—like those working with Resource Generation and Bolder Giving—making a conscious effort to use their money for systemic change. These are the people who launched the Tax Us More campaign because they understand that concentrated wealth isn’t good for anyone. While not perfect, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett have gathered dozens of Americans with considerable wealth with their Giving Pledge. But even with the best of intentions, Gates, Buffett, and other men and women with inherited wealth don’t know what it’s like to live paycheck to paycheck and they don’t live in the communities they seek to support with their philanthropy. As Peter Buffett points out, “Over and over, I would hear people discuss transplanting what worked in one setting directly into another with little regard for culture, geography or societal norms. Often the results of our decisions had unintended consequences.”

Strategic grantmaking has become a popular trend in the world of philanthropy, but it is not without considerable flaws. Strategic grantmaking has the allure of familiarity to donors and foundation leaders from the profit-sector: Set a goal, establish quantitative outcomes, and use financial incentives to get results. Some aspects of this are hard to argue with. I think we can all get behind the idea of monitoring impacts to ensure our grantmaking is doing what it’s intended to do. But, as Bill Schambra explored here at Nonprofit Quarterly, strategic grantmaking almost always puts philanthropists in the driver’s seat, which leads to focusing on problems that might not be a community’s priority, a tendency to ignore problems that activists on-the-ground try to draw attention to, unreasonable timelines, and attempts to quantify things that are not measurable in numbers.

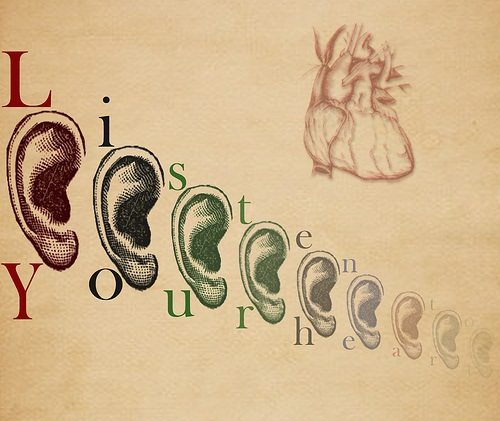

But there is a better way: one focused on listening.

Foundations all across the country are approaching grantmaking differently. North Star Fund in New York, Headwaters Foundation in Minneapolis, Hawaii People’s Fund, and MRG Foundation, the organization I lead here in Portland, Oregon, just to name a few. A quick look at our websites will show that we all have different funding priorities, donor bases, and strategies. But we all have one thing in common: The power and responsibility to allocate resources is vested in activist grantmakers, individuals deeply embedded in the communities we support, instead of donors, corporations, or foundation staff—who can be far removed from the impacts of poverty and injustice.

Activist-led grantmaking creates a different relationship between wealthy donors and our foundation, which, in and of itself, supports social change. When wealthy people relinquish decision-making power and step aside to support those most impacted by injustice, we get the most responsive funding decisions, shift power dynamics in our communities, and create institutions that reflect our values for true equity.

Buffett deserves praise for recognizing that he doesn’t have all the solutions, “My wife and I know we don’t have the answers, but we do know how to listen. As we learn, we will continue to support conditions for systemic change.” When foundations don’t listen to and learn from those most impacted by injustice, they miss the opportunity to get at the root cause of problems to create long-term change and better lives for those they serve.

We need more philanthropists like Buffett who are willing to listen and more foundations who follow the lead of those closest to the problems we’re trying to solve if we’re ever going to fund anything but Band-Aids.