“THE BURDEN OF FORMALITY” BY KEVIN SLOAN / WWW.KEVINSLOAN.COM

Editors’ note: This article is featured in NPQ‘s blockbuster summer 2013 edition: “New Gatekeepers of Philanthropy.”

Invocation

There is a Moment in each Day that Satan cannot find,

Nor can his Watch Fiends find it; but the Industrious find

This Moment & it multiply, & when it once is found

It renovates every Moment of the Day if rightly placed.

William Blake, “Milton”

Writing at the time of the American and French Revolutions, Blake, the prophetic poet, did not mean, by “Satan” and his “Watch Fiends,” what we mean today; he meant the spirit of rationalism. He had seen England’s common grazing land displaced by “dark Satanic mills.” He foresaw us as imprisoned inside a large clock, which could, by an act of the moral imagination, become once again a town green where lambs graze.

A Personal Perspective

I once taught literature, then taught estate and financial planning to advisors, and now teach fundraisers and advisors how to collaborate to work with high-capacity donors. Whether it is metrics in fundraising (the art of the ask) or metrics in business (the art of the deal), I find that the failure point in gift planning is a failure of the moral imagination. That failure might be rectified if fundraisers stepped up from asking for money to helping donors achieve a better life through more imaginative, better-planned philanthropy.

Visionary and effective planning for large gifts in the context of a donor’s ideals, overall wealth, and family situation is necessarily a team exercise. The wealthy potential donor already has advisors who call that donor a client. You will, as a nonprofit gift planner, have to work with or against advisors if you are to tap into the larger dollar. How advisors will respond to you depends on whether you have “control of the case.” To gain control, your key strength is your willingness to engage in the conversation of purpose—one to which you are well suited and well positioned, working for an organization devoted to what is best in humanity. Properly conducted, that conversation of purpose, meaning, and community will drive and redirect the otherwise dry and often self-regarding planning processes that run their course daily in the offices of attorneys, CPAs, insurance professionals, investment advisors, and others who serve the wealthy. You can lift that conversation to a higher level, with a more inclusive view of what counts as winning in life for ourselves, our families, and our communities.

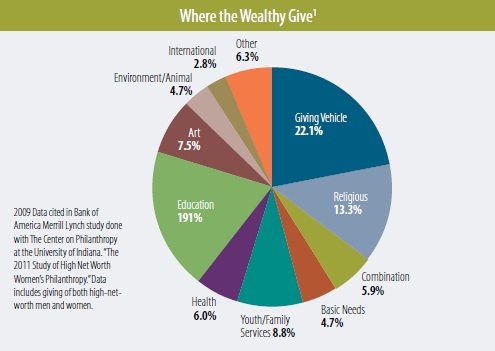

Advisor-Driven Philanthropy as Money into charitable Buckets

Consider the chart above showing giving by issue area. Much of it is what a fundraiser would expect. Now consider the largest slice, at 22 percent of the total. That is money not to a specific cause, but into charitable tools. It is a wealth transfer, deductible as allowed by law. But rather than going directly to a charity like your own, these funds go into a “bucket” from which grants or disbursements will, eventually, be made. The recipients of that biggest slice are foundations, donor-advised funds, charitable lead trusts, and charitable remainder trusts. Who funded that study? Bank of America Merrill Lynch. When encouraging financial advisors to discuss philanthropy with their clients, I say, “Look at that slice, my friends—that is money you can manage!” For nonprofits to access that money, to get it from charitable tools, they will often have to work with or against advisors who control the case and who have a financial stake in the outcome.

Roughly 97 Percent of Gifts from 3–5 Percent of the Assets

Bryan Clontz heads Charitable Solutions, an organization that helps nonprofits, particularly community foundations, accept and process gifts of what are called “noncash assets.” These include commercial and personal real estate, private business interests, tangible personal property, patents, mineral interests, timber, crops, and much else. According to a presentation Bryan made in 2012 to professional advisors on behalf of Community Foundation of South Jersey, “more than half of affluent investors’ assets are held in noncash assets. Cash only represents 3–5 percent.”2 Yet, he says, gifts from noncash assets are estimated to be less than 3 percent of total giving. Exact data, Bryan would acknowledge, is hard to come by, but the point is clear: Nonprofits today get most of their gift dollars from a small pot of cash assets, while the largest pot—noncash assets—goes largely untouched. To activate these noncash assets for charitable purposes, the fundraiser must work with donor advisors who have expertise in this area.

The Closely Held Business Market

Daniel Daniels and David Leibell are tax attorneys who specialize in the closely held business market. In a 2011 workshop paper delivered to the Southern California Tax & Estate Planning Forum, “Estate Planning for the Family Business Owner,” they acknowledge that scholarly data on the size and scope of closely held business is hard to find, but cite as indicative these findings from Family Firm Institute’s Global Data Points:

Approximately 90 percent of U.S. businesses are family firms, ranging in size from small mom and pop businesses to the likes of Walmart, Ford, Mars and Marriott. There are more than 17 million family businesses in the United States and they represent 64 percent of Gross Domes- tic Product and employ 62 percent of the U.S. work force.3

These business owners face significant challenges. As Daniels and Leibell note: “Only a little more than 30 percent of family businesses survive into the second generation, even though 80 percent would like to keep the business in the family. By the third generation, only 12 percent of family businesses are still viable, shrinking to 3 percent at the fourth generation and beyond.” 4 These business owners are often deeply committed to their community. They are prime candidates to give back, but cannot do so at full capacity unless advisors are engaged to help liberate the closely held business wealth for charitable purposes.

How Generous Are These Closely Held Business Owners?

In The Philanthropic Planning Companion, citing a 2010 Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund survey, Entrepreneurs & Philanthropy: Investing in the Future, Brian M. Sagrestano and Robert E. Wahlers write, “Entrepreneurs are consistently more charitable than other high-net-worth individuals. Entrepreneurs are individuals for which 50 percent or more of their net worth comes from a family-owned business or start-up company. They are far more generous than those individuals who acquired wealth by inheritance, investment asset growth, or investment in real estate.”5

The Fidelity study cited by Sagrestano and Wahlers found that 53 percent of entrepreneurs said charitable giving was a key part of their estate plan. Their motives include gratitude, empathy for others, and their having the resources and freedom to do it.6

What Is on the Successful Business Owner’s Mind?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As baby boomer business owners consider transitioning their firms—either to employees, outside buyers, or family members—they ask larger life questions. To cite Dr. Lee Hausner and Douglas K. Freeman, The Legacy Family: The Definitive Guide to Creating a Successful Multigenerational Family, these are among the common issues:7

- What will I do with the rest of my life?

- Without the business, I am nothing.

- Without me, the business is nothing.

- Nobody can run it as well as I can.

- They may run it better than I did.

- I need some place to go every day.

Also on the owner’s mind are questions like these:

- What will we get if we sell?

- How much do we need for ourselves?

- How much is enough, but not too much, for the heirs?

- How can we have an impact on our community?

- How can we reduce taxes in favor of heirs or charity?

- How can we pass on our values as well as our valuables?

Behind it all, as a generational soundtrack, you can almost hear Peggy Lee singing, “Is that all there is?” Is that all there is to being successful, building a company, having a family, selling the business in style—is that all there is? The answer The successful business has to be no. The business owner is looking for a second act after success, and is a perfect candidate for engagement with a local nonprofit.

Closely Held Business Wealth in Your Neighborhood

The successful business people I am describing are your neighbors. You may do business with them. You may have bought your car on their lot, you may eat in their restaurant, the food on your table may have been grown on their farm. They eat in their restaurant, may service your air conditioner, or have built your home. One may own the strip mall where you pick up your dry cleaning. They may own the trucking company, the gas station, or the McDonald’s franchise. Your last trip to the airport may have been in a cab from a fleet they own.

These are people who are rooted in the local community, often in a faith tradition. Some are from families who have lived there forever—born in the hospital like their parents before them and expecting to be buried in the same churchyard. Others are first- and second-generation immigrants from India, China, Cambodia, Mexico, Guatemala, or Vietnam, hoping to bring relatives here and put down roots. Asked the deeper questions, these families—who do not give big yet and who are not connected to community foundations or to the philanthropic networks—often express gratitude, obligation, and the need to make it come out whole by devoting their self-made wealth to leaving behind them a community worth living in for their children.

Your Role as a Fundraiser: Conversation Starters

Advisors often see their role narrowly, as helping clients with the mechanics of amassing, preserving, growing, and transferring wealth. They often see themselves as tax, legal, or financial strategists whose goal is to optimize money. Clients, however, are also human beings, not just “wealth holders.” They are parents, citizens, potential donors, and civic leaders. Some may see themselves as on a journey whose end point is eternity. They need and want someone—perhaps you—to work with them to set direction, and to see their own life whole, as a narrative with purpose, dignity, and significance. Here are good questions you can ask:

- Where would you like to have an impact now, later, at death, and beyond death? On yourself and on your family, certainly. On your business, of course, and on your money. Is there anywhere else?

- Are there things you meant to do earlier in life, when you were starting out, that you have not yet done? How can you get back to that while you still have time?

- What principles will guide your legacy plan to date?8

- How wealthy do you want your children to be?9

- Where do you volunteer or serve on boards?

- What keeps you awake at night?10

- Do you believe you have a responsibility to society? 11

- If your family had a crest, what would be the motto? 12

- Has past giving reflected your hopes?13

Donor Narrative

These questions, or ones like them, when they register, elicit an often rambling and inconclusive self-narrative. The potential donor will begin to talk, often hesitantly, sometimes abashedly, and in leaping arcs of half-finished stories, about his or her life and what it means and where it tends. To literary ears, it sounds like a tale in search of what Frank Kermode called, “the sense of an ending.” Psychologists tell us that “life review” is a life stage, setting in as we age, and is not optional. At a certain age, it becomes almost compulsive. We need our lives to come out even. Given enhanced life spans today, life review even at older ages can lead to new life—a new life as a giver and civic leader—so that the whole of life is redeemed or enhanced. By listening to the stories and connecting them to what your organization does, you can redeem the time by helping the donor achieve a purpose beyond money, a purpose that makes that life complete.

Stepping into the Conversation of Purpose

Having heard any number of excuses over the years from both advisors and fundraisers—ranging from “It’s not my job”/ “I’m not paid to do it” to “I don’t know how”—I was in need of solace. I met with Rabbi Mordechai Liebling, teacher of theology and social justice organizing and of fundraising, and asked him if he and the rabbis he trains would risk these larger questions with donors. His answer came in one word: “No.” He then said, “Phil, what you need to know is that as rabbis we have three roles. First, we are prophets.” I protested that the questions about meaning are prophetic. “Yes,” he said, “they are.” “Second,” he said, “rabbis are preachers.” I protested that these questions about life and death are pastoral, to a fault. He agreed. Then he said, “Third, we are also employees of the temple.” He was teaching me that these larger philosophical questions are terribly difficult to raise, even for someone with pastoral training.

Mordechai eventually came to The American College of Financial Services, where I teach, to role-play a fundraising interview on camera. He did a great job, but to me he sounded like a salesman. “But,” I said, “Rabbi, you don’t sound like a rabbi. That woman in front of you is going to die. Is this the best you can do?” His eyes flashed. He sat back down, and said: “Your last will and testament is your final teaching. What do you want it to say?” The hair rises on my neck each time I repeat those questions. That is the prophetic voice.

Each of us, rich or poor, as we plan our final affairs, deserves three heartbeats where those questions or others like them hang in the air. The spirit may enter. The spirit may not. But if a person—call that person a donor, call that person a client, call that person your neighbor—dies without such a question having been asked, what dream of a better life in a better world will be buried with him or her?

What gives you the right to ask larger questions of those with wealth, power, and influence? It is a matter of alignment. You have every right to ask others questions you have asked yourself, the ones that led to your own life course in service to an ideal. In the orbit of this “donor” or “client,” you may well be the one person with the courage, or temerity, to lead from purpose. You may be their last chance to align plans and purpose before the books close forever.

Please lead. When you come to your highest-capacity donors, please lead from the best in yourself and from the mission of your organization, so that the best in us will live on for those who come after us. Who are you to do it? Who else will?

| Who Works with Closely Held Business Owners? Most small businesses are very small. But local successful businesses comprise a lucrative market for a cross-disciplinary cadre of professionals, including attorneys, CPAs, bankers, brokers, and insurance agents. Such professionals provide income and estate tax planning, groom businesses for sale, do business valuations for sales and charitable transfers, provide investments, or sell life insurance to provide liquidity for estate tax and business transfer purposes. Among the Credentials Recognized in This Market

Places to Network with Advisors

How to Connect through Your Own Networks

|

Phil Cubeta, CLU, ChFC, MSFS, CAP, is The Sallie B. and William B. Wallace Chair in Philanthropy at The American College of Financial Services.

Notes

- Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, supported by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, The 2011 Study of High Net Worth Women’s Philanthropy and the Impact of Women’s Giving Networks (Indianapolis: Bank of America Philanthropic Solutions/The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, 2011), 8, newsroom.bankofamerica.com /files/press_kit/additional/Study_HNW_Womens _Philanthropy.pdf.

- Bryan Clontz, “Creative Charitable Planning with Non-Cash Assets,” April 3, 2012. In the presentation, Clontz cited a 2005 study by Spectrem Group and Realty Times. In fact, Bryan is speaking from his own extensive experience. For those who work in this market, it is quite clear from client balance sheets that the bulk of assets, particularly for self-made business owners, are rarely cash heavy. These owners invest in what made them rich in the first place—illiquid, closely held businesses, as well as land, collectibles, and other things that do not trade on an exchange.

- Daniel Daniels and David Leibell, “Estate Planning for the Family Business Owner,” a presentation to the Southern California Tax & Estate Planning Forum, October 26–29, 2011. They cite as their source Global Data Points, Family Firm Institute, Inc.

- Ibid.

- Brian M. Sagrestano and Robert E. Wahlers, The Philanthropic Planning Companion: The Fundraisers’ and Professional Advisors’ Guide to Charitable Gift Planning (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), 93.

- Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund and Ernst & Young, Entrepreneurs & Philanthropy: Investing in the Future, 7, www.fidelitycharitable.org/about-us/news/11-12-2010.shtml.

- Dr. Lee Hausner and Douglas K. Freeman, The Legacy Family: The Definitive Guide to Creating a Successful Multigenerational Family (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 132.

- Charles Collier, Wealth in Families, 3rd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2012), adapted from questions on page 1.

- Ibid., adapted from a question on page 5.

- Joe Breiteneicher, head of The Philanthropic Initiative at the time, in a conversation with the author.

- Collier, Wealth in Families, adapted from a question on page 5.

- Breiteneicher, in a conversation with the author.

- Tracy Gary, adapted from a question in her Inspired Legacies, 3rd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2008), 53.