Editor’s Note: In 2010, NPQ published this article by Clara Miller, then of the Nonprofit Finance Fund and now of the FB Heron Foundation. In it, she discusses four pre-existing conditions that could have made nonprofits particularly vulnerable to the Great Recession. NPQ invites its readers to write in about their own experiences with any combination of these problems during the downturn. Was Miller on the mark? NPQ has seen these very factors play out in arts organizations across the country, but let’s hear from you!

As the recession loomed, Nonprofit Finance Fund (NFF) realized that its clients—borrowers, financial advisees, and grant recipients—had been exposed to a virulent flulike virus. The financial crisis was like a pervasive, all-encompassing malady. And like health workers fighting a true epidemic, NFF’s clients would be exposed to the disease and expected to fight it simultaneously. There was no vaccination program, although there were some swift and thoughtful efforts by funders to maintain funding levels, release restrictions on grants, and provide real-time relief. And it was well understood that the disease could be fatal.

Like flu sufferers, organizations with preexisting conditions were likely to be more vulnerable. Flu fatalities and close calls were more common among those suffering from, for example, chronic asthma. And similarly, the economic H1N1 epidemic (or financial “plague”) was likely to hit certain organizations harder. NFF’s funder partners and Community Development Financial Institutions colleagues saw the same patterns.

Indeed, some difficult cases were predictable. Organizations that had suffered from the financial equivalent of chronic asthma were hit hard. They were weak from years of marginal operation and further hollowed out by what NFF terms “pretty bad best practices.” These practices include a tendency among funders to routinely restrict cash;? a public obsession with pointless metrics (e.g., overhead rate and fundraising costs);? government’s declining reimbursement coverage; and a mounting list of unfunded compliance and comportment mandates from all sides. And contributing to the prevailing weakness was everyone’s tendency (managers, board members, and the public) to do more with less and thus weaken organizations’ built-up service-delivery capacity.

Another group of victims in the sector was less predictable. These organizations had played by the nonprofit rules, were likely to have four- and five-star ratings, and boasted enviable business models that were carefully built according to so-called best practices in capitalization. They also owned their buildings, used long-term bond financing, and steadily built their endowments. Unrestricted net asset balances were handsome. Savvy, connected business folk peopled their boards.

Still, a surprising number turned out to have been vulnerable, too. And while most members of these groups have worked hard to convalesce, they may remain members of the “walking wounded” for years to come.

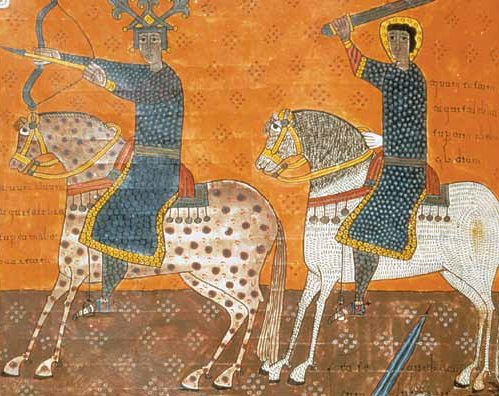

The Four Horsemen

The H1N1-like financial virus that wrought havoc on these predictable and unpredictable victims also bedeviled banks, homeowners, and businesses throughout the economy. Quite simply, the culprit was declining—and increasingly uncertain—revenue. This simple reality hit all organizations in some way: large and small, nonprofit and for-profit, rich and poor. And the factor that predicted vulnerability can best be summed up by Peter Bernstein’s pithy description of financial risk: “not having cash when you need it.”

Well, that seems straightforward enough; we might even call it the quintessence of a “duh” moment: if your organization doesn’t have cash, it suffers financially. But even strong nonprofits that looked great on paper became vulnerable, and their struggles surprised many. So what went wrong?

From the capitalization point of view, these organizations had some shared characteristics. And we call these carefully built elements that made them vulnerable the “Four Horsemen of the Nonprofit Financial Apocalypse.” Any one horseman can make an organization more vulnerable in an uncertain, changing economy. But when these horsemen ride together, they can be fatal.

Horseman One: Too Much Real Estate

For most board members and nonprofit advisers (or, for that matter, senior managers) it’s practically axiomatic that owning your facility is better than leasing one. Why pour rent money down the drain when you can build up equity? If you own a building, you can borrow and leverage your growth.

In NFF’s experience, this prevailing “wisdom”—even in good times—isn’t reliably true. The prospective returns on commercial real estate (or personal homeownership) don’t usually square with nonprofits’ commercial realities. Even in the best of circumstances, acquiring a facility that doesn’t push an organization’s fixed costs to an uncomfortable level is devilishly difficult.

NFF research indicates that about one-third of organizations that acquire facilities can manage these shoals well. This third ends up with a building that cradles the program and works financially: a true triumph. Another third manages to complete the building but arrives gasping on the beach; as a result, this group becomes the walking wounded. Among this group, program quality and financial health are typically impaired for years. For a final third, financial imbalance pervades operations to the point of requiring reorganization or even extinction. What’s more, the tendency to value real estate purchases over other capital investment—building the technology platform, refreshing programmatic assets, or adding firepower to the development department, for example—forces more important parts of the organization’s operation—and future—to go without capital investment. Especially in a rapidly changing economy, the opportunity costs are high.

In the boom times that preceded the recent crash, some capital campaigns and facility planners in the nonprofit sector experienced irrational exuberance as well. Building campaigns and acquisitions regularly outstripped carrying capacity. Some strong organizations built or acquired more than they needed in the belief that market value would continue to increase and that they would continue to grow. In some cases, they reasoned that having excess capacity would allow them to go into the landlord business (and collect reliable revenue from rent).

For overbuilders, the market has been a cruel teacher. Even where nonprofits didn’t expect rental income, those that anticipated straight-line growth have experienced interruption, decline, and vagaries in revenue, so the increased fixed costs of a larger facility (and more managerial and programming expenses) have become a burden. Moreover, quick fixes are elusive. Especially in a down market, it’s difficult to sell a building or lease surplus space to ease this burden.

Thus, for prospective landlords, overly large buildings have imposed a double whammy: not only do these landlords face the burden of higher fixed costs but the collapse in commercial rents has made tenants rarer (or nonexistent), eliminating expected rental income. Most made their revenue and expense projections at or near the top of the real estate market, so market rent declines will have real and probably long-lasting financial consequences during a slow recovery.

Horseman Two: Too Much Debt

While there’s much talk about nonprofits’ lack of access to debt, research by Robert J. Yetman of the University of California, Davis, demonstrates that nonprofits resemble their for-profit peers (in terms of size and type of operations) with respect to the levels and kinds of debt deployed. Historically low interest rates attracted nonprofits just as these rates did everyone else, even though that situation created too much borrowing.

In the recent downturn, debt—especially high levels of debt where borrowers and lenders overestimated the amount of reliable revenue available for repayment—has affected even strong organizations. Those taking out mortgages or issuing bonds to finance purchase or construction have found that their debt is an additional component of increasing fixed costs. And ironically, some of the most creditworthy—medium-size and large organizations with excellent bond ratings—find themselves working their way out of this fix. Because they could borrow at low rates and, in some cases, against endowments that pumped out historically high returns, they did. When operating revenue dropped, they had to cut programs and services to stay afloat. As Stephanie Strom notes in her September 23, 2009 New York Times article, there are numerous cases where robust organizations with excellent bond ratings, the best access to capital, and “management savvy” overreached, and their capital structure made them less flexi-ble, with negative consequences.

Horseman Three: “Under Water” Balance Sheets and Negative Liquidity

Over the years, one of the so-called pretty bad best practices that NFF has observed is a purported formulaic path to financial stability through the successive addition of assets (generally increasingly illiquid) to the balance sheet: first a leased space, then the cash reserve, then a building, and then, finally, the endowment.

For many, amassing an endowment represents a “nirvana” state, where fundraising (and related pain) ceases and programs are amply funded; the sun shines on beaming board members who have tidy, constructive discussion about investment options (as opposed to unseemly wrestling sessions about who’s written their annual check); and every meeting includes thoughtful planning based on a reliable, multiyear gush of investment earnings from the endowment.

Myriad factors make this progression impracticable (and even undesirable) for most organizations, but it persists. And it has for many years, despite evidence to the contrary. Even in 1940, Margaret Grant and Herman Hettinger noted that endowments provided potentially unreliable revenue: “Endowments are becoming more difficult to build up and the income there from has been found uncertain when most needed, in depressions [emphasis added],” they wrote.

By 2008, many endowments were heavily invested in equities, and portions of most portfolios were “under water” (i.e., had declined in value to a level lower than their purchase price). A cash-strapped organization faced the unsatisfactory choice of (1) selling (and thus realizing a loss while awaiting recovery); (2) holding on while accepting that the returns would be meager or nonexistent; or (3) borrowing against the devalued portfolio or another asset (consider New York’s Metropolitan Opera borrowing against its Chagalls to raise cash).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This is not to say that some organizations do not have a compelling mission-related need for an endowment or that having cash reserves, sinking funds, and similar assets on the balance sheet are not evidence of enterprise-savvy financial management. The problem is our sector’s automatic-pilot approach to making these decisions.

Horseman Four: Torturous Labor Economics

Finally, an important part of the sector’s commercial proposition is difficult labor economics, which makes commercial operation problematic. Managing workforce dynamics has been a historically challenging aspect of nonprofit enterprises, and one of which seasoned managers are well aware.

Some nonprofits require highly specialized talent, which is expensive and requires ongoing care, feeding, and investment. Economies of scale available in the for-profit world are not always applicable to nonprofits (consider symphony orchestras and research universities). Other nonprofits are labor-intensive because of quality and regulatory considerations (consider skilled nursing facilities and day-care centers).

Despite difficult times, nonprofit workforce reductions are often impossible or highly undesirable. Consider the impracticality of these scenarios: “We’ve decided to lay off the brasses, the second violins, and if revenue doesn’t rebound, the oboist” or “We’re not going to give our Nobel laureates lab privileges for a week a month,” or “We’ll just reduce nurse count in the intensive-care unit by half.” Hmmm . . . brain surgery, anyone? While sometimes possible, productivity gains from economies of scale and technology simply do not follow the path of those for for-profits. And in many large institutions, labor unions add another layer of complexity. Unlike other horsemen, however, this one is more closely related to mission, making it essential to some organizations’ core values rather than an optional strategic choice. I would argue that building a business that supports this “human capital” as it delivers on organizational mission is paramount.

It’s not difficult to see why the Four Horsemen wreak havoc in an environment of disappearing and declining revenue, especially among the Charles Atlases of the sector.

What’s most worrisome, however, is that the dominant institutional model in the sector—represented by the Four Horsemen—compels organizations to grow in a hermetic, almost automatic, way and create businesses that are highly illiquid and vulnerable to economic flux. And despite seemingly robust balance sheets, many nonprofits are starved of the capital needed for adaptation to a rapidly changing economy. If the recession has taught us anything, it’s that net assets are not the same as “cash when you need it.”

Within the sector, the best and the brightest within leading organizations are questioning long-held assumptions and reviewing their business models to determine how to adapt to a changing economy. They have asked questions that may prompt change that goes beyond simply coping with the current financial woes. Given the new economic reality, they want to build an enterprise that can succeed despite the realities that (1) the pull of place has declined, (2) a global market has developed, (3) “intermediaries” have lost much of their authority and utility, and (4) technology has redefined the market. They are reexamining what happened, why, and how they can push the reset button.

How Did We Get Here?

The sector suffers from a one-size-fits-all growth-and-change model that is largely the result of habit and reduces cash accessibility. Because capital investment in the nonprofit sector was traditionally associated with either a building purchase or a restricted endowment, these factors alone have become the default setting for capital investment. Moreover, the financial best practices put in place by the nonprofit sector are largely unrelated to sound capitalization. Instead, they focus on reporting, tax-law compliance, and counterproductive pretty bad best practices. Finally, both donors and recipients routinely put money into hermetic compartments that limit how funds are used rather than connect funds to what they are meant to accomplish. Taken together, these tendencies have led to widespread institutional fragility.

The one-size-fits-all model also has long-lasting opportunity costs. When capital is invested in assets that aren’t mission critical, it means that other, more important investments can’t be made. Capital routinely invested in a prescribed progression of fixed assets can’t play the multiple roles that change requires. An organization boxed into an overly large building, for example, may lack the option to invest that cash in more critical areas, such as mitigating operating risk, upgrading technology, burnishing the brand to appeal to national corporate sponsors, or building talent (including a scaled development department). Capital is also required for other kinds of change, such as improving revenue reliability, improving operating efficiency, or reducing overall cost. In this approach, real estate is not off the table;? it is simply one asset among others in a more diversified business investment strategy.

What Now?

To be perfectly clear, the message here is not that all owned property, debt financings, endowments, or human-capital strategies are bad. Over the years, NFF and others have financed buildings with debt and tax credits throughout the country, and helped organizations find ways to build other parts of their balance sheets, including endowments, cash reserves, and sinking funds.

And NFF continues to see great projects. Based on practice and research, however, we do believe that these projects are frequently undertaken in a kind of managerial sleepwalk. They are subject to a kind of groupthink about capitalization that fails to examine alternatives and is unlikely to align capitalization strategy with program, capacity, and market. This just isn’t good enough anymore.

Change is here, and many are behind the curve. Business models and markets in the economy as a whole have changed, and those in the social sector must change with them. And this change is happening. An increasing number of young people entering the sector are platform- and sector-agnostic. The one-size-fits-all institutional model has been subject to “disruptive innovation” in real time. If institutions don’t pay attention, they will invest themselves into irrelevance and, from a mission point of view, lose their way.

We need to broaden our capitalization horizons. Our sector tends to embrace an enterprise model built on a static set of assumptions about financial risk, investment, and return. As the world changes, we need to provide capital investment for growth within the sector’s great organizations without confining deployment to a specific asset class or use.

Funder practice and social-sector management norms need overhaul. As NFF has learned, pretty bad best practices are deeply ingrained in the sector. It’s truly empowering for funders and nonprofit leaders to become more enterprise savvy rather than focus on compliance (mainly with trust, estates, and tax law), comportment (mostly focused on reporting hygiene), and pretty bad best practices.

The first step is to understand what capital is and isn’t. Many in the sector use the word capital interchangeably with money, income, and revenue, which creates conceptual squishiness and imprecision that undermine progress. One approach is to think of capital as the “factory:” the built capacity of an organization that supports the delivery of programs and services. These built programs then reliably attract revenue that pays for them, and this situation becomes “sustainable.” Growth capital (philanthropic equity) changes that factory—makes it bigger, smaller, develops new offerings, invests in efficiency, develops a system to measure effectiveness, and so on. It is required for any change. Replenishment capital takes care of the usual wear and tear on the built “factory”: depreciation, the need for program refreshment, technology replacements, and so on. And both types are deployed to ensure that revenue to fund organizational mission can flow more reliably in the future. Capital builds the factory (no matter what it’s spent on), and revenue pays for regular delivery of programs and services (no matter what it’s spent on).

The Real Risk Is to the Public

This is a difficult but defining time. We must keep foremost in our minds that our sector exists to serve the public. So the question we must continually push ourselves on is this: how is the public best served by the choices we make? As difficult as it is for us to confront, the real risk is not to our jobs or those of our colleagues, it’s the risk to the public: that a child will go home to an abusive parent, that a homeless veteran will not find help, or that a talented teen won’t be able to go to college. This is why the failure of a nonprofit can be so painful. If organizations sense growing danger, they will move quickly to ensure that constituents are best served or as little harmed as possible, and the rest is secondary.

| What to Do if You Are in over Your Head |

| Even if the Four Horsemen are gaining on nonprofits, what can these organizations do now? NFF believes it’s useful to think about this problem in two “bites”: (1) coping (that is, getting through the worst of the recession and preserving an organization’s current programs as much as possible); and (2) changing (that is, rethinking and redoing the business model and programming given a new reality).

Successful coping is often a central skill for nonprofit managers. Coping enables them to sharply assess the reliability of revenue, adjust and readjust expenses accordingly, and sometimes make tough choices that allow mission-critical services to be preserved, even when it means layoffs and furloughs. Successful changing requires access to capital along multiple dimensions, which allows organizations to adapt as the environment evolves. For various reasons, the principles of sound capital investment are foreign to most funders, boards, and managers in our sector, but suffice it to say that capital—whatever the purpose—is not the same as revenue to support the regular delivery of services. One way to think about capital is to understand that it funds the temporary deficits incurred before it attracts enough revenue to support program delivery going forward. Thus, capital is temporary, while revenue—at least in good times—is not. Organizations that have taken advantage of our Tough Times services have found help on the coping and the changing fronts. First is a program profitability analysis, which breaks down individual lines of business and analyzes their contribution (or lack thereof) to the bottom line. This informs decisions on coping with real-time information. Organizations also like the related scenario planning tool—which is more about the medium and long term and the implications of various coping strategies. Organizations can project the financial implications of what-if scenarios, including mergers, asset sales, retrenchment, transferring programs to other organizations, and so on. And some of these coping strategies involve major enterprise change and, yes, capital. Finally, it may seem counterintuitive, but this is the time to invest in change and growth. Expanding work that is core to your mission and competency; undertaking a radical redo of the business model to a more virtual platform for service delivery; acquiring the right facility at a bargain-basement price; investing in program assets, such as new artistic work, are just a few we’ve seen. And the bottom line is that all these “changing” activities require capital.—C. M. |

In 2010, Clara Miller was president and CEO of Nonprofit Finance Fund, a community development financial institution that is a leading source of financing and advice for nonprofits nationwide.

Copyright 2010. All rights reserved by the Nonprofit Information Networking Association, Boston, MA. Volume 17, Issue 1. Subscribe | buy issue | reprints.