October 17, 2014; San Francisco Chronicle and The Daily Telegraph

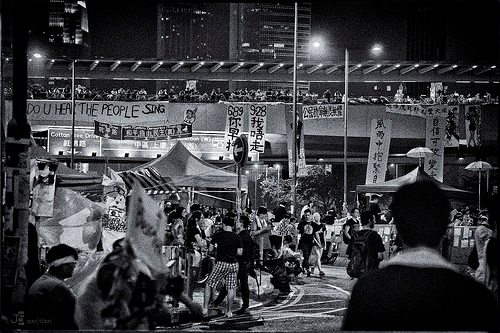

Pigs and umbrellas would hardly seem to pose much of a direct threat to China’s government, but officials trying to quell support for the growing Occupy Central movement in Hong Kong have decided otherwise. As the Associated Press reports, a number of the most respected artists in eastern Beijing’s Songzhuang art district have been detained or taken from their homes for going public with their views, particularly via the Internet.

The artists of Songzhuang, a popular tourist destination, had recently seemed to enjoy “a rarely seen degree of creative and political freedom,” according to AP’s Jack Chang who reported on the police actions Thursday. In fact, not long ago, artist Li Dapeng “couldn’t wait to show off his series of oil paintings depicting Chinese families, leaders and aristocrats—all topped off with grotesque pig faces.” Now, all that has changed. Police roam the streets, and artists who only a few weeks ago were inviting foreign journalists in to see their new works now warn visitors away from their studios.

The first signs of trouble came on October 1st when poet Wang Zang was arrested after posting a picture of himself on Twitter holding a blue umbrella with one finger raised, showing solidarity with student pro-Democracy protesters of the “Umbrella Revolution” in Hong Kong. As readers know, the umbrella has become a powerful symbol in that movement.

【大陸淪陷區區民王藏黑衣光頭打傘撐香港:眼前黑暗,抗命的中指和拳頭不黑暗】#香港#占中#公民抗命#伞花革命pic.twitter.com/mU80dfRfz1

— 王藏 (@wang_zang) September 30, 2014

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“The ubiquitous umbrella symbol of Hong Kong’s protests emerged out of necessity,” says the Daily Telegraph’s chief foreign correspondent, David Blair, “due to weather and as a form of defense against police tactics” spraying tear gas. Ironically, this is the opposite of how the umbrella symbol has been used traditionally. According to Edward H. Miller, an academic at Northeastern University in Boston, from the days of Neville Chamberlain in pre-WWII England through the Kennedy and Nixon years, an umbrella was the emblem of appeasement. “If you are compromising, you are umbrella man,” he said, but now, “the umbrella is being used for the opposite purpose (in Hong Kong)…It’s a symbol of strength, a symbol of defiance.”

The world of the artists of Songzhuang has been flipped on end, too, from a time of staying safe by, as Chang says, “avoiding official harassment by following a few tacit rules: If they produced provocative work, they showed it only to each other, and if they sold it, they did so privately. Most importantly, they kept a low profile.” But now, as he quotes painter Tang Jianying as saying, “If you’re in public, you have to watch what you do. If you’re on the Web and you speak too freely, they’ll get you.”

Numbers vary, but according to Radio Free Asia, “a total of 33 activists across China have been detained since September 22nd for publicly supporting the Occupy Central movement in Hong Kong, which is calling for public nomination of candidates for the 2017 elections for the territory’s chief executive…Of those, 21 are in Beijing, and seven are from the Songzhuang Artists’ Village, according to the Weiquanwang rights website.” The Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) group, which collates reports from rights groups inside China, says 23 people are being held under criminal detention. Three have received administrative sentences, while 35 have been held under some other form of police custody.

Chang also reports that watchdog groups, including Amnesty International, are saying, “Free speech restrictions have tightened during the nearly two-year-old government of President Xi Jinping with police detaining dozens of lawyers, journalists and activists and closely monitoring non-political groups such as Christian churches and community libraries.”

On Wednesday, Xi went further, telling “the country’s most well-known directors, writers and artists gathered in Beijing that their art should be patriotic and reflect socialist values, according to the official Xinhua News Agency. That message was prominently displayed across state media and dominated that evening’s main newscast,” according to Chang.

This represents another example of what Si Han, curator of Chinese Collections at the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities in Stockholm, has called crossing “the invisible red line” of arts censorship in China. But, as events have shown, it’s increasingly difficult to keep freedom under wraps.—Susan Raab