December 4, 2014; University of Chicago News

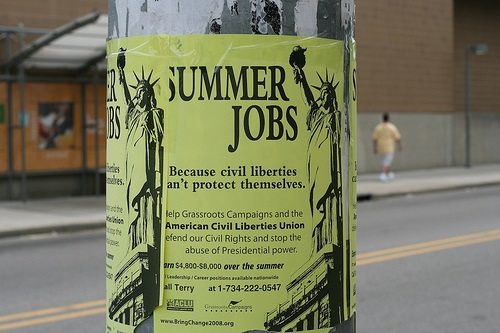

Youth employment is recognized as a solution to decreasing the summer spike in crime, but is it worth the cost, and does it have impact beyond the summer months? A new study of Chicago youth living in thirteen high violent school areas documented a 43 percent drop in violent crime during employment plus the thirteen months afterwards.

The study explored the effect of part-time employment on 1,634 youth from thirteen high-violence areas of Chicago. Students participating in the program were almost entirely minority and more than 90 percent were enrolled in free or reduced lunch during the school year. About one-fifth of the students had been previously arrested and about a fifth had been a victim of a crime.

Students participating in the study (ages 14-21) were randomly separated into three groups. One group was employed for 25 hours a week for eight weeks at minimum wage ($8.25 per hour). A second group was employed for 15 hours a week, along with participating in ten hours of social-emotional learning classes intended to educate participants on understanding and managing aspects of their behavior that might interfere with successful employment. In addition, both groups of students were matched with an adult job mentor to assist them in managing employment barriers. The third control group was not offered employment through the program.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The objective of the study was to answer the question, does summer employment have lasting impact on youth? It was overseen by University of Pennsylvania criminologist Sara Heller. The 2012 study was a collaboration between the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services, the University of Chicago Crime Lab, and One Summer Chicago, a local and county government partnership created in 2011. The program, named One Summer Plus, employed students in diverse positions, including as camp counselors, community garden workers, and assistants in city aldermen’s offices.

The study documented a lasting impact on youth behavior. Administrators worked with the Chicago Police Department to identify results both during employment as well as thirteen months after employment. The study found that students in the first and second groups were arrested for violent crimes 43 percent less than the control group. Students were slightly more likely to be involved in property and drug-related crimes, but the amount was statistically insignificant. The study did not document any differences in behavior between students in the two employed groups.

The 2012 study results were even more significant given the high rate of unemployment among youth. The 2010 employment rate for low-income black teens in Illinois, nine percent, was less than one-fourth that of higher-income white teens, at 39 percent. During that summer, youth employment was at a 60-year low, particularly for low-income minority teens. Additionally, in 2013, One Summer Chicago received 67,000 applications for 20,000 employment opportunities.

Often, leaders measure impact of these types of programs in monetary terms alone, leading to drastic undervaluation. In the 2012 program, each employed student cost $3,000, including $1,400 in wages plus $1,600 in administrative costs. Societal benefits of reduced crime are estimated at $1,700 per student. But youth living in areas of low employment and high criminal activity experience other benefits, including learning the importance of work as well as good habits they can use throughout their lives.

With the recession ending, employment is rising, but youth are often the last to find employment. Currently, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the overall youth unemployment rate is 14 percent, down only two percent from a year before. This means there are an estimated 5.6 million youth between the ages of 16 and 24 that are neither enrolled in school nor employed.—Gayle Nelson