April 30, 2015; New York Times

Dionne Searcy’s article in the New York Times has it right in one way on what is happening to the rural hospitals of America but underemphasizes an important part of the rural hospital story.

Beatrice, Nebraska, is an “isolated rural community [that] has lost a lot of the energy of its heyday, when shoppers roamed downtown sidewalks, freight trains rumbled past the Big Blue River, and streets clogged at quitting time as factory workers spilled out of their plants,” Searcy writes. However, it maintains “its economic pulse thanks in large measure to the Beatrice Community Hospital and Health Center, housed in a sprawling new building of concrete and green glimmering windows on the outskirts of town.”

The Beatrice hospital, until 1976 the Mennonite Deaconess Home and Hospital, is a nonprofit institution with a number of related nonprofit affiliates. It is, Searcy writes, an “economic anchor” for the community. “Those [rural] towns that have been able to attract hospitals and other health care facilities have emerged as oases of economic stability across the nation’s heartland,” she says. She acknowledges that rural hospitals are facing challenges and many have closed in recent years, but she doesn’t give many specifics as to why that might be—and whether Beatrice might be similarly challenged at some point.

Searcy writes that government support is critically important for rural hospitals—for example, the designation of some rural hospitals as “critical access hospitals” so that they qualify for better Medicare reimbursement rates. But the article doesn’t explain what is killing so many of Beatrice Community Hospital’s rural peers: the failure of many rural states in the Midwest and Southeast in particular to expand Medicaid eligibility.

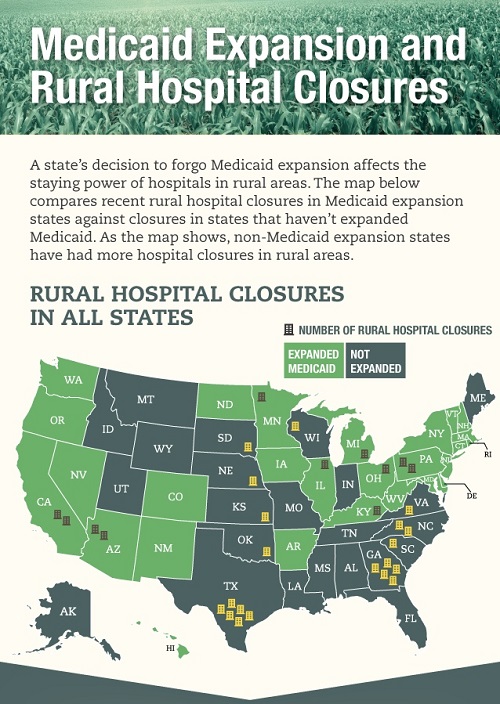

According to Families USA, “a state’s decision to forego Medicaid expansion affects the staying power of hospitals in rural areas.” In a December 2014 infographic on rural hospital closures, rural hospital closures since January 2010 in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility numbered 11, while there were 20 rural hospital closures in non-expansion states.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It makes perfect sense. Hospitals in states that have expanded their Medicaid eligibility find that their free charity care provision declines. The reduction in charity care patients means greater financial stability for rural hospitals. Larger urban hospitals handle some of the charity care load due to economies of scale or through income earned through specialized services that rural hospitals may not be able to offer. According to a USA Today article that described rural hospitals as in “critical condition,” the pace of rural hospital closures has increased. For survival, some rural hospitals are trying to link up with larger urban hospital chains to achieve the economies of scale they’ll need to weather their burden of uncompensated charity care cases. Given other requirements that rural hospitals face under the Affordable Care Act, notably the move toward electronic records, the planned reduction in Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, and the penalties they incur for having too many readmissions, rural hospitals face financial challenges that can be assuaged to extent by expanding Medicaid.

“Even in the poorest communities, small hospitals can thrive,” Searcy writes, and that is true. She describes the expansion of Field Memorial Hospital in low-income Centreville, Mississippi, a town of 1,600 people, which is opening a new facility as a result of a federal economic development program. That may work for the moment, but the long-term prognosis for rural hospitals in both Mississippi and Nebraska may be shaky. Both states have decided not to expand Medicaid eligibility. That leaves many moderate-income people in the coverage gap between traditional Medicaid on one side and federal health insurance subsidies on the other.

Ultimately, notwithstanding assistance that a rural hospital might be able to get through economic development programs, rural hospitals will live or die based on the revenues and expenditures involved in their delivery of healthcare. Searcy is right that rural hospitals can be economic anchors and perhaps even economic sparkplugs for their otherwise isolated and sometimes very low income communities. But in the shifting structures of hospital care, rural hospitals themselves may need the economic boost that comes from expanded Medicaid, else they become increasingly uncompetitive and financially troubled.—Rick Cohen