A few days ago, Michael Kaiser’s DeVos Institute published a study of the top 30 Black and top 30 Latino arts organizations and made recommendations for how to improve diversity in the Arts and Culture field. This study got the attention of several news organizations, including the Nonprofit Quarterly’s newswire.

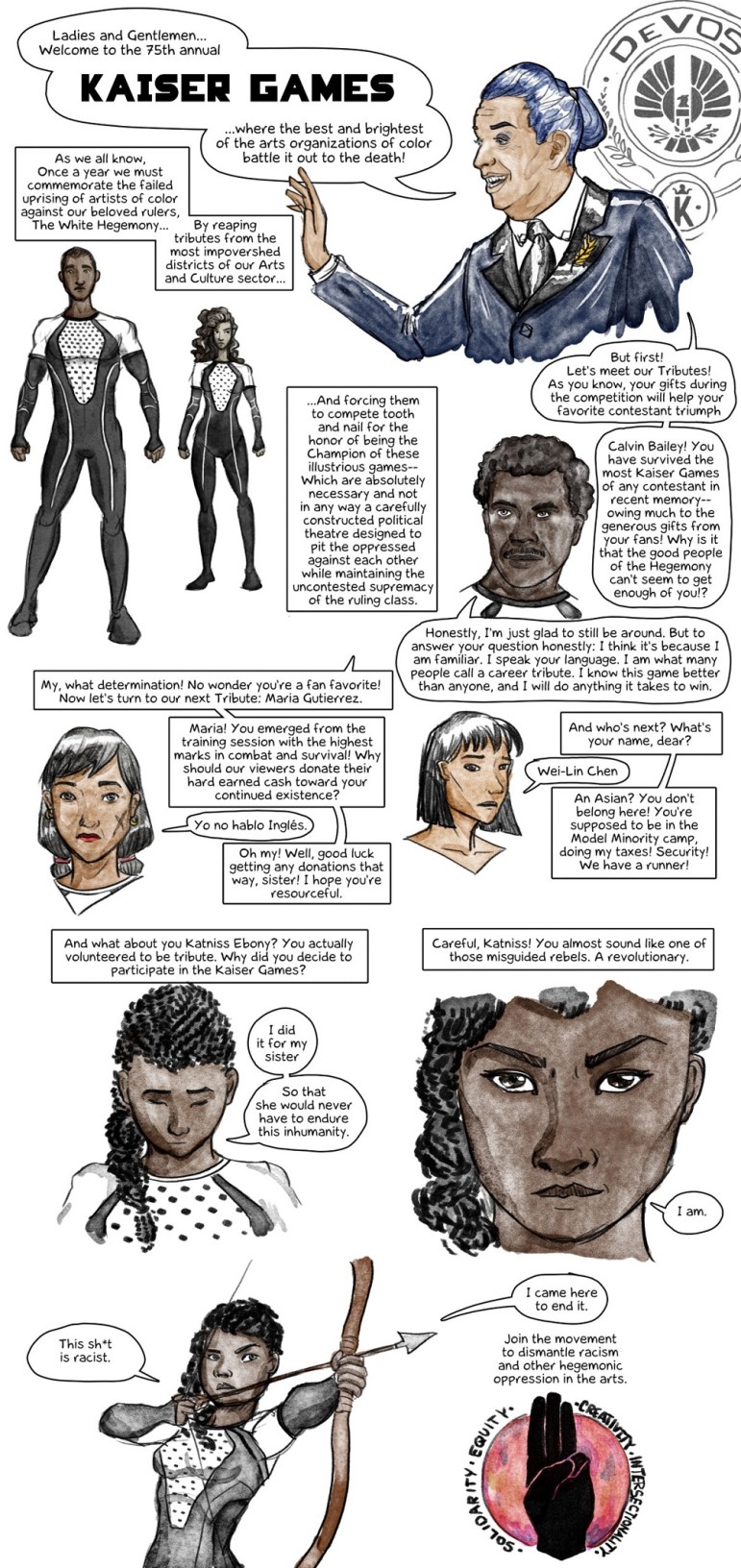

Here’s my response in comic form:

Michael Kaiser, chair of the DeVos Institute, took a look at the data, which showed some stark and humbling statistics about the financial health of Black and Latino organization:

The median annual spending for the big arts groups on the DeVos list was $61.1 million in 2013, compared with a $3.8-million median budget for the 20 largest African American and Latino arts groups in the study. Median means half the organizations in a category are above that figure and half are below.

The report said that minority-focused arts organizations’ most debilitating weakness has been difficulty in attracting private, individual donors, a demographic whose charitable giving far exceeds the grantmaking of foundations, corporations and government.

Let’s consider those numbers for a moment: The control group (read: dominant white orgs) on average have annual budgets roughly 16 times the size of the average budgets of the largest Black and Latino arts organizations in the nation.

This doesn’t come as a huge surprise, considering how Holly Sidford’s 2013 study found that only 10 percent of arts and culture grant dollars went to support “marginalized communities” (which include communities of color). In addition, it’s not at all surprising that individual giving at these organizations would be also far lower than the control group — particularly since White households’ median wealth is about ten times larger than that of Latino households and about 13 times larger than Black households.

What did come as a surprise was Kaiser’s recommendations after seeing this data:

Funders may need to support “a limited number of organizations,” says the report by the University of Maryland’s DeVos Institute of Arts Management, “with larger grants to a smaller cohort that can manage themselves effectively, make the best art, and have the biggest impact on their communities.”…

“It’s not politically easy or palatable, but it’s a potential solution that does need to be considered,” Kaiser said. “I am concerned that so many organizations are just holding on, with so little resources that they can’t create the size and quality of work that draws more donors and audiences. They get sicker and sicker. If there can’t be more funding, some funders will have to make choices.”

Let’s step back for a moment — we’ve got a whole bunch of data that shows that Black and Latino organizations are categorically and critically underfunded; that rich people (who are disproportionately white) ignore arts organizations of color; and that because of this racist funding pattern these organizations face monumental challenges to achieve good financial health — and the DeVos Institute suggests that our response should be funding fewer Black and Latino organizations and have them duke it out Hunger Games-style so that only a few remain.

Moreover, the study goes on to indict Black and Latino communities for the supposed complicity in the underfunding of their cultural institutions:

However, this gradual accumulation of wealth did not immediately or necessarily translate into philanthropy directed to cultural organizations. Then — similar to the present day — many African Americans tended to direct their charitable support to churches, social service providers, and civil rights organizations…

The DeVos study seems to ignore the drastic effects of institutionalized racism, which inhibited wealth accumulation for the black community like redlining and white flight. It also seems to assume that black wealth is somewhat comparable to white wealth, which we know is patently false, at an order of magnitude.

More important for the health of arts organizations of color has been the way their own boards were constructed. Traditionally, the boards of these organizations were formed by community leaders who supported the work of the artists from their communities and who believed that these organizations were of great benefit. But these leaders did not typically have access to major arts funders, especially individual donors. These boards did not have the same power to give and raise funds as their mainstream counterparts.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Black and Latino community is again being pathologized as the root cause of their cultural institutions’ poor financial health, and not the broader racist systems that would make it nearly impossible for a community of color to support a cultural institution at the same level as the dominant white society.

In 1991, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater had a budget of $6.5 million, raised less than 5 percent of its contributions from individual donors, and was facing bankruptcy. A substantial board restructuring in 1992–93 resulted in a new board capable of powering the growth of the organization. Today, the Ailey organization has a budget of $35 million.

Kaiser has long held up the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater as a model organization and has used it in the past to chastise other organizations of color for their lack of success. Even stranger, while the study lionizes Alvin Ailey for its singular success, the study fails to disclose that Kaiser, the chair of their own institute, was the executive director of Alvin Ailey during the period in which the organization was allegedly saved from its own devices. The important and valid points in the analysis of the dire state of Black and Latino arts organizations are undercut by the study’s thinly veiled self-congratulatory preoccupation with DeVos Institute’s leader and literal White Savior.

The fawning over Alvin Ailey also sidesteps the thorny fact that nearly the entire administrative staff and a majority of the board of trustees’ executive committee of Alvin Ailey is white. While it’s obviously important for white people to be active participants in the dismantling of racism, one must wonder why financial health for a Black or Latino organization is reliant on centralizing white people into the decision-making and fiduciary bodies within the organization.

Where are all the Asians? And all the other people of color?

The DeVos Institute study starts out by highlighting the demographic projections for Black and Latino populations in the U.S. as evidence of the need for increased diversity in the arts. While paying passing lip service to other groups outside of Black and Latino communities, all of us (Asian, Pacific Islander, Indigenous, Arab, etc.) get completely excised from the history of people of color in the arts. This is in spite of the fact that Asian Americans, in particular, are the fastest growing ethnic group in the U.S. and are projected to overtake Latinos as the largest ethnic group by 2055.

While I understand the importance of recognizing the unique challenges facing Black and Latino organizations, this seems to continue to feed into the model minority myth, which postulates that the API community is exemplary and have achieved economic success and therefore are separate from questions of racism or racial oppression. This is particularly stinging after Nicholas Kristof’s widely panned recent op-ed, “The Asian Advantage.”

This myth of Asian exceptionalism and perceived achievement masks the reality of how Asian/Pacific Islander (API) Americans are excluded from the creative sector, particularly from positions of power. Consider how despite all the alleged achievements we’ve amassed, there are still zero APIs leading among the top 100 nonprofits in the nation. APIs only account for 2.5 percent of board seats among those top nonprofits. And also consider how the API community only receives 0.3% of foundation investments for the past 25 years.

We need to stop pretending like APIs aren’t part of this conversation too.

Well, what are your solutions, Jason?

I’ve laid out a bunch of them in two articles on the subject—“I Got 99 Seats, but Wage Equity Ain’t One” and “What We Talk About When We Talk About Transforming the Field”—but here’s the TLDR:

- There needs to be a massive restructuring in how funds are distributed by the American philanthropic community (both institutional and individual). Given that it is highly unlikely that we will be able to convince wealthy individuals to start giving en masse to Black and Latino (or people of color groups more broadly), it should be the responsibility of institutional funders, who have an explicitly stated mission and moral obligation, to make up the gap. And I’m not talking a measly few grants, here and there. I’d ideally like to see institutional arts funders start devoting a minimum of 50 percent of their funding to POC arts groups to make up the difference, instead of the 10 percent they are currently devoting.

- If we want to see a rise in individual giving to POC orgs than we need to advocate for public policy and arts administration that sees more of the economic growth going to people of color. Increases to the minimum wage, earned income tax credit, expansion of SNAP and other anti-poverty programs, restoration of collective bargaining rights, an end to unpaid internships —these are a few that come to mind.

- Increasing technological capacity for arts organizations of color. We’re quickly approaching a world where it’s becoming possible to launch and run businesses with lower and lower overhead, but only if you’re able to leverage the efficiencies enabled by technology. These resources are even more important for organizations of color, who are not only more financially disadvantaged, but who are less likely to pursue technology-related skills in higher education.

This article was originally published by Fractured Atlas on medium.com and is reprinted with permission.