February 12, 2017; Boston Globe

Bob Hohler, an investigative sports reporter for the Boston Globe, has produced a remarkable article on the insider-enriching culture at a large Boston foundation. The Yawkey Foundation II, which has been active since 1982, was much enriched with some of the proceeds of the sale of the Red Sox in 2002. The insider culture Hohler describes is one where institutions that are connected with trustees are very well treated, as are the trustees themselves. Meanwhile, the institution has made grants of more than $350 million while growing to $420 million in assets.

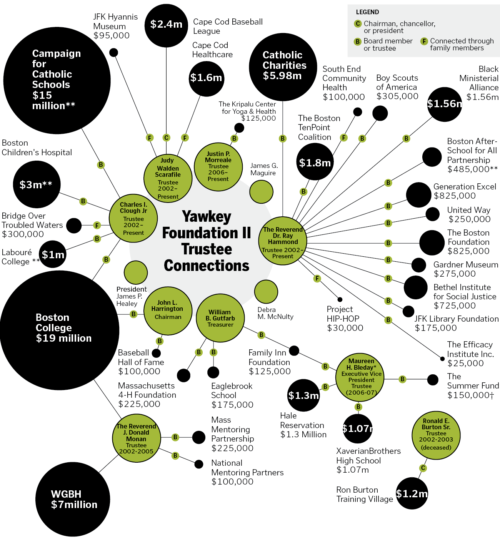

Hohler references the foundation’s “double legacy.” He says that the foundation’s trustees “have funded one another’s special interests, taken sizable fees, and engaged in practices that then-state attorney general Tom Reilly tried to prevent when proceeds from the sale spawned the largest charitable fund in New England sports philanthropy.” Concerns about conflicts of interest on the board of trustees date back to that time:

The foundation has been watched closely by Reilly since it reaped $420 million from the 2002 sale of the Boston Red Sox, whose longtime owners, Tom and Jean Yawkey, established the foundation. Reilly has criticized the foundation for favoring wealthier institutions over grassroots groups, and last year he imposed conflict-of-interest rules on its board that stipulate that no trustee “will propose any grant to, or transaction or arrangement with, any entity with respect to which the Trustee is an Interested Person.”

From the sale in 2002 forward, reports Hohler, Attorney General Reilly was concerned that so much charitable money would be poured into a foundation that essentially operated as a “closed little club.” In fact, he was sufficiently concerned that he made the foundation sign a good governance agreement, which was subsequently dispensed with in 2005—in retrospect, maybe not such a good idea. Since then, writes Hohler, the foundation did away with its anti-nepotism rule, steeply increased the compensation of trustees, and eliminated term limits for the board’s chairman. More than $84 million—one of every four dollars—has been granted to organizations with which the trustees have ties.

Using a now-familiar defense, the Yawkey Foundation II has said none of those grants violated its conflict-of-interest rules “because board members with ties to those organizations did not propose the grants or discuss them with other trustees, and recused themselves from voting on the requests.” This reliance on disclosure and recusal, of course, wears thin in organizations where influence is clearly traceable in results.

“In all our grantmaking activities, we adhere to well-recognized procedures and best practices that guide the operations of private foundations to ensure we avoid conflicts,” the foundation’s president, James P. Healey, said in a statement. “We are fully transparent about all our grants in our public filings, our published annual report and on our website.” That transparency reveals a half-million-dollar investment in the Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health, where the charity’s attorney and board member learned to teach yoga.

And in the case of trustee Ray Hammond, and Yawkee grantees Bethel Institute for Social Change and Generation Excel, both of which function out of his church, Bethel AME, and are funded by the foundation, the relationships appear way too close and self-serving, according to Pablo Eisenberg, a founder of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Public and Nonprofit Leadership. The Bethel Institute has received 58 percent of its funding from the foundation since 2009 when it started, and Generation Excel has paid $30,000 a year to Hammond over seven years.

“Even if it’s not technically illegal, it doesn’t pass the smell test to me,” Eisenberg said.

Hammond expressed surprise when the Globe informed him how much personal compensation he received from Generation Excel. But he asserted that every dollar paid to him came from funds donated by other charities.

Hammond is hardly alone, as the relationship map from the Globe below affirms.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

John L. Harrington has chaired the board for a decade despite the fact that the original governance agreement with Tom Reilly mandated that the chairperson would serve no more than one year at a time. Harrington helped Mrs. Yawkey run the Red Sox until she died in 1992, then started managing her estate. The governance agreement also barred family members of trustees from joining the foundation board, but Harrington’s daughter, Debra M. McNulty, now sits on the board.

Additionally, the trustees are paid, even though Thomas Yawkey, who originally dedicated $20 million to what is now the Yawkey Foundation, stated that “any individual trustee of the foundation shall serve without compensation.” Since Harrington became chair, trustees have received an annual average of $26,000 for working one to four hours a week. Harrington himself has received an average of around $41,500 annually.

But it does not end there: Harrington and Gutfarb, the executors of Yawkey’s estate, created the Boston Trust Management Corp. to run the Yawkey foundations.

Harrington, Gutfarb, and their associates have drawn large sums from the firm since the Sox sale.

Gutfarb and James P. Healey, the former Sox vice president for broadcasting, each took nearly $4.8 million in compensation—an annual average of $369,000—from Mrs. Yawkey’s foundation between 2002 and 2015, the most recent year for which the information is available. Another former Sox employee, Maureen H. Bleday, received $2.7 million over 10 years, and Harrington was compensated $1.1 million over four years before he ended his paid management role in 2006 at the age of 70. Healey and Bleday remain on the payroll.

The foundation said the compensation is determined by its trustees and based on annual studies by outside consultants. The corporation operates on a break-even basis, according to the Yawkey board.

Ray Hammond says when he began serving on nonprofit boards decades ago, many foundations were “the fiefdoms of banks, wealthy businesspeople, and people from the religious community, who in many cases were not directly engaged” in the communities they served. Now that nonprofits are beginning to select trustees who are intimately engaged in helping their communities, he says, problems of perception may arise.

At times, he said, “You’re between a rock and a hard place.”

Readers may recall that this is not the first foundation to face the Globe’s intense scrutiny. The paper’s famed Spotlight team took on some of the fiefdoms referred to by Hammond 15 years ago, and Rick Cohen followed up on those cases ten years ago. At that time, Cohen wrote:

It is good but insufficient for foundations to promulgate standards by which they can govern themselves. In the cases highlighted by the Globe, there was little evidence that the foundation sector’s trade associations took action against philanthropic malefactors. It will take more than blind faith in the self-correcting DNA of the nonprofit sector to clean up these kinds of abuses. As the series and its aftermath show, government regulators have to get up to speed, the nonprofit sector’s self-regulating advocates have to swing into action, those on the inside of troubled institutions have to blow the whistle, and the press has a crucial role in pursuing accountability in philanthropy. In due time, unless self-regulatory efforts are bolstered with government regulation and the capital to support oversight and enforcement, there will be more Globe-like stories about foundations.

The fact that the problems of insider self-dealing (or perception of same) are reappearing now and specifically at the Yawkey Foundation despite Tom Reilly’s warnings testify to the need for consistent external oversight. Some cultures, especially where there is so much money involved, just don’t give up that easily.—Ruth McCambridge