February 11, 2017; NBC News and the International Business Times

Over the past eight years, the Department of Justice (with some notable bipartisan support) has helped move issues ranging from police and court reforms to improved incarceration practices to center stage. However, as Jeff Sessions takes over as U.S. Attorney General, the job of criminal justice reform has become ever more clearly seated at the state level. The job of local advocates is to build or maintain momentum in state legislatures and municipalities.

Some significant accomplishments and experiments have indeed taken place at the state level. However, when centrally important data emerges, we long for a central presence, a role that may need for now to be picked up by philanthropy and nonprofits—some representing communities, and others made up of law enforcement personnel.

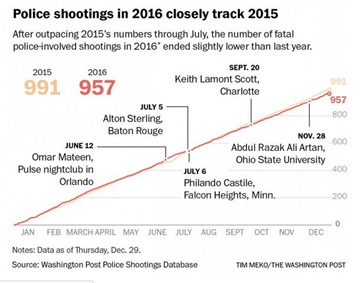

“Fatal Shootings By U.S. Police Officers in 2015: A Bird’s Eye View,” using a database developed by the Washington Post to examine shootings of unarmed victims, found that “black men accounted for about 40 percent of the unarmed people fatally shot by police and, when adjusted by population, were seven times as likely as unarmed white men to die from police gunfire.”

Justin Nix, an assistant professor of criminal justice at the University of Louisville and one of the leaders of the study, told the International Business Times that this disparity remained even after refining the raw data to account for other factors that might affect the outcomes: “Black suspects were more than twice as likely as white suspects to have been unarmed. And that’s after we controlled for things like mental illness, threat level, age, etc.”

From Nix’s perspective, “A shooting of an unarmed person could be considered a threat perception failure on the part of the police. Police shoot unarmed people when they fail to accurately assess a threat, which could be due to implicit racial bias, or bias that arises from subtle unconscious assumptions, as opposed to overt racism. “If you can accept that assumption, then we showed that the citizen’s race is predictive of those threat perception failures, which we think is evidence of bias, and presumably implicit bias, although it’s impossible to tell.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The study’s analysis goes beyond the individual tragedies that too often dominate our newsfeeds. Its findings are in unfortunate harmony with the recent U.S. Department of Justice reviews of policing in Baltimore and Chicago, which illustrated patterns of racial bias.

The report noted that officers may unconsciously develop biases over time. “In other words, the police—who are trained in the first place to be suspicious—become conditioned to view minorities with added suspicion,” according to the report. The authors said the findings have policy and practical implications, and researchers suggested that police departments should better train officers on how to reduce bias. The researchers also suggested that departments invest in body cameras to increase transparency.

But, who will take such information and enforce a solution under a federal administration that appears to have a very different take on race and criminal justice? Again, many of these battles will need to be waged at the state level and with nonprofit leadership. C.J. Ciaramella writes for Reason that some large foundations and nonprofits haven’t lost a beat: “The American Civil Liberties Union is beefing up its Campaign for Smart Justice with the goal of reducing incarceration by 50 percent by 2020. In the coming months, the ACLU will roll out a roadmap for reducing incarceration by half in each of the 50 states.”

Some readers may recall that the ACLU received $50 million from the Open Society Foundations to work on criminal justice reform in 2014, and that campaign has only grown.

“States were ground zero for the battle against mass incarceration before the election and ground zero after the election of Donald Trump,” Udi Ofer, the director of the ACLU campaign, told reporters in press briefing last month. “This a battle that must be waged and won at the state level.”

— Martin Levine