September 11, 2017; Forbes

According to a new study coauthored by two Washington, D.C. nonprofit think tanks, Prosperity Now (formerly CFED) and the Institute for Policy Studies, America’s already large racial wealth gap, far from narrowing, will grow ever wider in the years to come, absent policy change.

The two institutes’ joint report bears the ominous title “The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Gap is Hollowing Out America’s Middle Class,” a clear riff on George Orwell’s classic The Road to Wigan Pier. It projects that, if current household wealth trends (as have occurred between 1983 and 2013) continue indefinitely into the future, by 2053 the median Black household would have a net worth of zero—meaning that at least half of Black households would have a negative net worth, with Latinx households hitting the same negative threshold 20 years afterward. By contrast, white households are projected to see their wealth increase.

Of course, long-term projections need to be taken with a large grain of salt. For example, median white household wealth fell in the Great Recession—so much so that the report projects that at the projected pace of increased white household wealth growth, median white household wealth will still be lower in 2073 ($147,000 in current dollars) than in 2007 ($161,400). In short, the past 30-year trend surely won’t continue as-is. But that hardly means that reduced racial wealth disparities are a sure thing. To the contrary, doing worse than projected is possible, too.

In any case, what is certain is that the trend lines are clear and negative. And they have been increasingly negative in recent years. For example, in 2007, median white household wealth was about 16 times higher than median Black or Latinx household wealth. By 2013, median Black or Latinx household wealth had fallen by more than 80 percent. As a result, even though white household wealth fell, too, the racial divide ratio widened considerable from 16:1 to a white-Latinx ratio of 58:1 and a white-Black ratio of 68:1. Given these numbers, it is hardly surprising that the report finds that if the current 30-year trend line extends to 2020, median White households are projected to own 86 and 68 times more wealth than Black and Latinx households, respectively.

Forbes contributing writer Erik Sherman points out the danger of these trends:

Two factors—wealth transfer and the advantages wealth provides—come together in ugly ways. We typically describe middle class status in terms of income. But, if you change the definition to wealth, meaning you’d need between $68,000 and $204,000 in household wealth—middle quintile White households have nearly eight times as much wealth as median Black households and 10 times as much as Latino households. Black and Latino families now have to earn two to three times as much as White families to catch up.

The report illustrates some ways this plays out. For example, 78 percent of households of color live above the poverty line, but only 45 percent own homes. In other words, even if you’re not in poverty, if you’re in a household of color, there is greater than a two-in-five chance that you don’t own your home and hence don’t benefit from land-value appreciation. By contrast, 90 percent of white households are above the poverty line and 71 percent own homes. So, for white households, if you’re not in poverty, there is nearly a four-in-five chance you own your home.

Another example: 72 percent of white households have more than $6,150 in cash savings, but only 43 percent of Black households and 39 percent of Latinx households do. Having cash savings can be a critical cushion to keep people out of the claws of predatory lenders; by contrast, not having cash savings can lead to an ever-deeper hole of debt.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

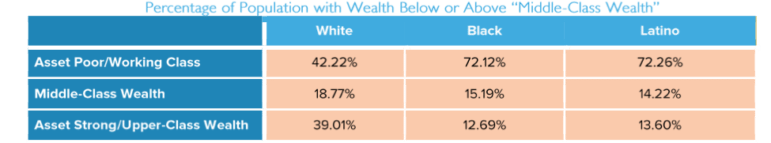

Another important finding in the report is buried below the headlines. As Rhonda Soto wrote in an article on the intersection of race and class years ago, “Discussing race without including class analysis is like watching a bird fly without looking at the sky: It’s possible, but it misses the larger context.” So, take a look at this chart drawn from the report:

The implications are clear. One is that a large percentage of white households —more than 40 percent—are asset-poor. Another is that some households of color—but fewer than one in seven—have accumulated significant wealth. (The report defines “asset strong” as having assets in excess of $204,000—in other words, well above the median white household wealth level.)

So, yes, not all wealthy families are white and not all people of color are poor, but, what is also frighteningly clear is that if our country keeps doing what it’s doing now, the result would be a country with an asset-poor majority, including a large minority of poor whites and a large majority of people of color, who are projected to become a majority of Americans by 2044.

What is to be done? The report authors focus on changing the federal tax code. Presently, $677 billion in tax expenditures are used primarily to subsidize upper-income households. These are things like the mortgage-interest deduction, the property tax deduction, the retirement savings deduction, and the college savings deduction. The report estimates that the average household with $50,000 in income gets a $226 tax benefit, while the average millionaire household gets a $160,190 tax benefit. So, yes, more equitable federal tax policy is very important. Still, federal tax policy alone is unlikely to make a major dent in wealth disparities.

The report, alas, gives little guidance to foundations, nonprofits, or movement activists of how to more effectively engage. But one can easily imagine some possible avenues:

- Broaden financial education programs beyond budgeting to include an understanding of the economy as a whole—something endorsed, at least after a fashion, by a federal reserve governor.

- Support efforts that result in community-based economic institutions that create jobs and generate community-based profits over time, as the Foundation for Democratic Communities did, when it partnered with community leaders to launch a community-owned grocery store. The result of the partnership was the opening of the Renaissance Cooperative in a Black neighborhood in northeast Greensboro, North Carolina, last year. The store is projected to employ 28 and generate over $300,000 in profits to community members in the first 10 years.

- Engage directly with movement efforts that advocate for and build new political and economic institutions, like the Movement for Black Lives network of organizations has advanced.

- Build links among nonprofits and movement activists by promoting—and, in the case of foundations—funding advocacy, as the Stand for Your Mission coalition has advised.

Clearly, it will take action in a wide range of areas to seriously reduce the racial wealth gap. As Sherman concludes in his article, the stakes are high:

Without programs specifically targeting people who don’t have wealth and need to build it, the country could become even more polarized by wealth inequality. Aside from its obvious inherent issues, such a direction could undermine the economy. If the median wealth of a majority of Americans is zero, there will be little to drive the economy as a whole, and that is a bad prospect for everyone.

—Steve Dubb