October 3, 2017; New York Times and Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Gerrymandering comes with baggage. It can be defined as the manipulation of the boundaries of an electoral constituency so as to favor one party or class. It matters little which party does the manipulation, and both parties are a part of gerrymandering efforts. As the Supreme Court heard the case of Gill v. Whitford on October 3, 2017, Justice Samuel Alito called gerrymandering “distasteful.” This is not the first time a reluctant Supreme Court has addressed this issue. And each time, the Court divides between those who feel the Court should not even weigh in and those who feel the Court is the only government body that should.

In May, NPQ wrote about the Supreme Court decision in a race-centered gerrymandering case from North Carolina, finding that race, when used as a factor to draw voting districts, was grounds for disqualifying those districts. Now, Gill v. Whitford, a case that focuses on Wisconsin, has brought the issue of partisan gerrymandering forward. The Justices are clearly divided as to whether this case falls in the Supreme Court’s wheelhouse. The four more conservative justices (Roberts, Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch) see it as a slippery slope for the reputation of the courts and the public’s confidence in them. The four more liberal justices (Ginsburg, Kagan, Breyer, and Sotomayor) see this as a must for a court decision in dealing with a crisis for democracy and upholding voting rights. The swing vote will fall to Justice Anthony Kennedy, who has long been troubled by extreme partisan gerrymandering—that is, if this case can show that Wisconsin’s voting maps have crossed a constitutional line.

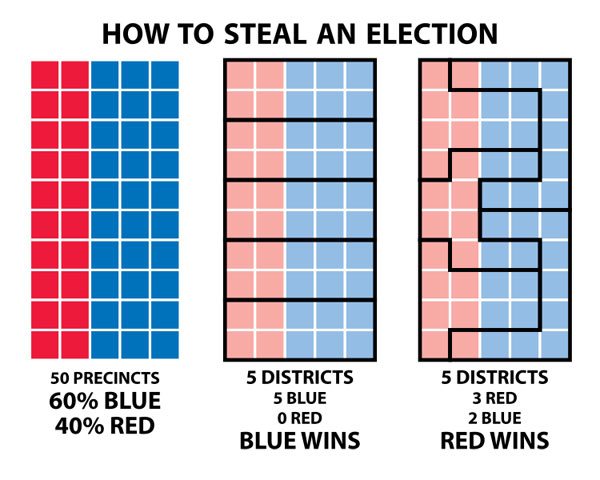

Differing from the North Carolina case, with its focus on race as the means of drawing political districts, the Wisconsin case is about politics and party. Such gerrymandering can entrench a party in control of legislative seats for years even when that party does not represent the majority of the voters in that state. This is where the terms “cracking” and “packing” come into play:

The plaintiffs say the Wisconsin Legislature used “cracking” and “packing” in 2011 to give Republicans an advantage. “Cracking” divides registered voters of one party among several districts to dilute their voting power. “Packing” groups them into a single district so their voting power is reduced in neighboring districts.

State legislatures have long used those techniques to the advantage of the controlling political party, and the effects have become more pronounced.

Resolving this issue requires a reasonable standard by which the impact of how the districts are drawn can be measured. This “measure” has been missing since the Court decided Vieth v. Jubelirer 13 years ago. In that case, the justices could not agree on when partisan redistricting diluted voting power because there was no test to prove it one way or the other. That test may now be available, and this Wisconsin case may prove to be the one to satisfy Justice Kennedy’s desire for such a measure, as his deciding vote in Vieth kept the door open.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In Gill v. Whitford, the court must first rule on whether the nine plaintiffs have standing when the court has previously ruled that plaintiffs in racial gerrymandering claims have standing only in cases challenging the individual district in which they live, not the whole state. Their case challenges the division of the state’s 99 legislative districts seven years ago in Republicans’ first chance to lead redistricting after 40 years of Democratic control.

In the first election after redistricting, the GOP won 60 out of 99 seats even though only 49 percent of voters statewide voted Republican in 2012. In the next election, Republicans won 63 seats with 52 percent of the vote.

“This is the product of better map-drawing technology utilizing more sophisticated data about an increasingly polarized electorate. The result, in too many states, has been a subversion of democracy as officeholders have wrested power from voters,” plaintiffs’ attorneys wrote in a court filing. They noted that the problem has become “more common, more severe and more durable” since the Vieth case.

The reluctance of the conservative justices to rule in this case was clear in Chief Justice Roberts’s extended remarks, expressing worry that the court would be viewed as partisan. “That is going to cause very serious harm to the status and integrity of the decisions of this court,” he said. Countering his concern was Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who stated, “What’s really behind all of this? The precious right to vote.” She indicated that if voters believe that the district maps have been drawn to favor one party over another, no matter how many people vote, then why will they bother to vote?

A lot is at stake in this decision—so much so that other elected officials have weighed in and offered their positions. Former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and Senator John McCain both stated their support for districts being drawn by independent commissions rather than by politicians. Both parties have used political gerrymandering to their advantage.

The decision in this case could rest with the vote of Justice Kennedy, if he can be satisfied that a “workable standard” has actually been devised to show when political gerrymandering has crossed a constitutional line.

Perhaps among all of the arguments offered in this case, the most fundamental question came from Justice Sonia Sotomayor when she asked, “Could you tell what the value is to democracy from political gerrymandering? How does that help our system of government?” The answer given—that it is about who is and who is not in power—did not seem to satisfy Sotomayor. It may not satisfy Justice Kennedy, either. And his vote seems to be the one that hangs in the balance.—Carole Levine