October 26, 2017; CityLab

The latest 10-year labor market forecast report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that “more and more of the country will be paid to take care of old people.”

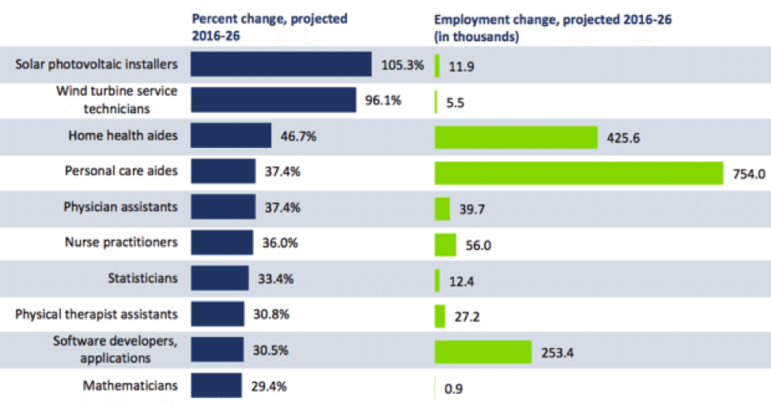

According to CityLab, “No occupation is projected to add more workers than personal-care aides, who perform non-medical duties for older Americans, such as bathing and cooking.” This and home-health aides are projected to contribute 1.1 millionjobs, or 10 percent of the expected 11.5 million total new jobs over the next 10 years.

This continues a long-term trend of growth. Recently, the nonprofit Paraprofessional Health Institute (PHI)—an organization dedicated to improving wages and working conditions in the direct care industry—noted that the number of immigrant care givers, overwhelmingly (90 percent) female, rose “from 520,000 in 2005 to 860,000 in 2015.” The report ads that, “when accounting for independent providers, approximately 1 million immigrants work in direct care.” Unfortunately, this is not a highly paid workforce. PHI date find that 40 percent of immigrant care workers and 44 percent of non-immigrant care workers rely on public benefits—i.e., food stamps and welfare—to make ends meet.

This past July, NPQ’s Karen Kahn wrote:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

By 2050, the number of Americans ages 65 or older will nearly double, growing from about 48 million to 88 million. Those who need the most assistance, the population of people over 85, is on track to triple, from 6.2 million to nearly over 18 million over the same time period. Many of these older Americans, along with younger adults with disabilities, need long-term services and supports. They may need assistance with personal care, such as dressing, bathing, and preparing meals, or with other types of daily activity such as paying bills, cleaning the house, or getting to medical appointments. When this support cannot be provided by a family member or friend, it is often provided by direct care workers—home health aides, personal care aides, or nursing assistants.

The opportunity for nonprofits to transform our economy is present. But it won’t happen by itself. There are some innovative models. For example, the Cooperative Home Care Associates (CHCA), a 2,000-employee business in the Bronx operated as a worker cooperative has been lifting working conditions and wages for decades. The firm, reports Fast Company, “guarantees workers full-time pay, whereas many agencies operate using contract workers. In addition, all CHCA workers get health care benefits—which, nationwide, is not the case for about a quarter of these workers. Finally, as worker-owners, CHCA members receive a share of the profits in the form of dividends. The president gets the same dividend as the newest home care worker, which usually averages around $200 to $300 a year.”

The importance of getting elevating wage and working conditions nationally throughout the sector cannot be overstated. As the BLS report cited above notes:

- Healthcare will continue its takeover of the economy. “The graying of the U.S. is quietly one of the nation’s most important economic events. Aging explains, for example, why jobs are projected to grow 50 percent slower in the next decade.”

- Inequality—by income, education, and geography—will continue to grow. “Jobs for people with bachelor’s degrees are projected to grow twice as fast as jobs for people with just high school degrees…there won’t be a shortage of either extremely low-paid work or highly paid work. But jobs earning between $30,000 and $50,000 are projected to grow slowly, as employment flags in manufacturing and retail.”

Those are current trends. But there is nothing inevitable about them. As an NPQ article pointed out last year, “nonprofits must try to stop adopting the unjust current operating environment and most dominant enterprise models as givens, and begin to consider sustainability of the workforce as a core principle. In direct care, sustainability of an expanding, well-trained workforce must be predicated on meeting workers’ basic needs: proper training, a voice, a living wage, and labor justice.”

In short, “Advocating for living wages, reasonable working conditions, and the attendant raises in contracting rates has to be every nonprofit’s business, if it is to be effective.”

—Steve Dubb