This morning, NPQ is proud to present the first of a regular series of columns by the FrameWorks Institute on how to improve the effectiveness of our messages on contentious social issues. This one is written by the esteemed Susan Nall Bales, who will walk us through the uses and abuses of narratives in communicating about immigration. While each column may use the example of a particular social issue, you need not be in that field to benefit from the instruction.

Struggling to find a path of action in the midst of the Reagan administration, Edward Said, the noted Palestinian American literary critic, warned: “The challenge posed by [the perspectives of Reaganism] is not how to cultivate one’s garden despite them but how to understand the cultural work occurring within them.”1

Struggling in the midst of the Trump administration, advocates can easily find themselves overwhelmed by the rate and volume of cultural products being generated. Nowhere is this more apparent than on the issue of immigration. A barrage of news has dramatically shortened the conceptual distance between crime, terrorism and immigration. The contemplated presence of even an imaginary wall reinforces the cognitive distinction between “us” (the public) and “them” (immigrants). And this is happening every day in every form of media, as we are subjected to daily demonization of immigrants who came to our country as children, who have temporary residency, or who come from countries with travel bans. This is the new cultural product of our time.

What are progressive policy framers to do? How should we think about what is being shaped and reconfigured by these activities? How can we think strategically about how to improve our cultural production to combat what is now in our drinking water? How can we make our ideas stickier and more persuasive?

Advocates are subjected daily to polls that purport to provide answers. But if you don’t understand how an engine works, you can’t repair it. What is the framework of interpretation that will help immigration reform advocates evaluate the cultural products in circulation and choose a better option? The same formula of theory plus evidence-based practice that is required for good policy development is needed to inform our framing efforts.

A good theory of cultural production should identify the questions we need to ask and point us in a direction to find answers. Sound practice should deliver answers in the form of evidence to drive our subsequent work. We should be able to kick the tires of our cultural products and make sure they hold up. How might we go about this?

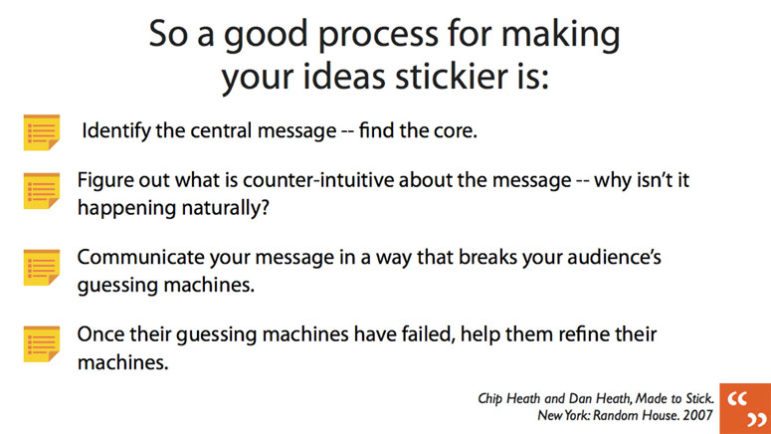

In their popular synthesis of the social science of opinion formation and change, Made to Stick,2 Chip and Dan Heath offer a succinct theory that can be adapted across social issues. It looks like this:

If we apply this theory to immigration, we can discern what kind of data we need to collect to drive an effective communications strategy. Not just any old poll or more data, but a refined recipe of data that can be subjected to particular questions. Drawing from FrameWorks’ multi-method investigation of how Americans think about immigration,3 let’s look at how each step of the theoretical model is answered in a systematic research process and how this totality results in a plan of action.

FIND THE CORE

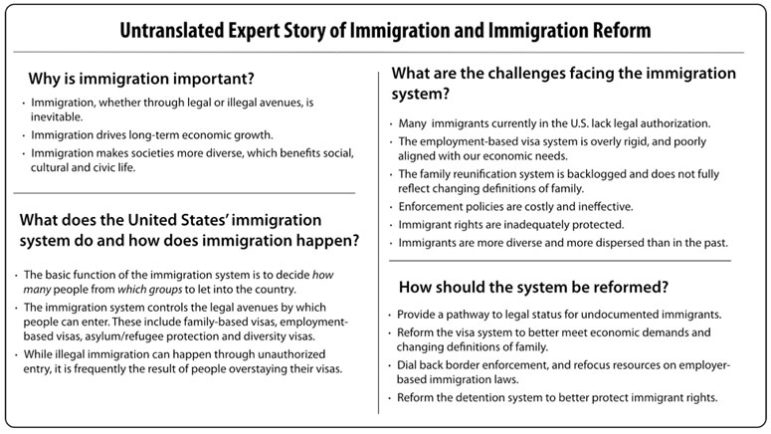

First, we must reduce the message to its gist, focusing on the key aspects of the immigration system that Americans need to know in order to effectively evaluate solutions. FrameWorks does this by interviewing thought leaders on a given topic and synthesizing their recommendations into a coherent draft narrative—what we call the “untranslated story.” This differs markedly from common practice, which tends to equate what is popular and resonant to the communications deliverable. On immigration, FrameWorks’ method yielded this composite:4

Put simply, as the National Academies of Science and others have attested, the United States needs to do a better job integrating immigrants into society and providing opportunities so they can achieve and contribute. In an ideal world, this simple set of messages could be delivered by advocates around the country and prove a potent cultural product. In reality, research shows, these messages will dissolve and dissipate in public discourse if left untranslated, leaving little trace.

WHY ISN’T IT HAPPENING NATURALLY?

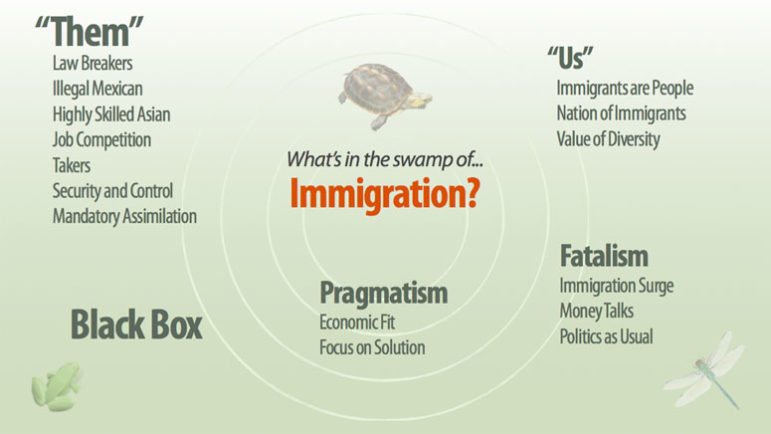

What prevents these simple messages from sticking? That is the challenge that the Heaths posed in their theoretical model, and the challenge that FrameWorks pursues via long-form interviews that examine the enduring beliefs and conceptualizations that Americans routinely bring to bear on the subject of immigration. FrameWorks uses the heuristic of a “swamp” of cultural models—a rich ecosystem of ideas that are grown and fed over time, that thrive or decay, become dominant or recessive—to explain what “eats” the expert message. Stubborn and persistent but also assailable and manipulable, cultural models are the overlooked obstacle that advocates ignore at their peril. Psychological anthropologist Bradd Shore explains that “the work of a policy framer is to change the salience of the models.”5 By changing the model that is foregrounded, we can move from an understanding that is “fuzzy” to one that becomes the default understanding, or the go-to way of thinking.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Swamp of Immigration poses key challenges for communicators.6

- Americans “otherize” immigrants, perceiving differences instead of similarities. This strong conceptual drive to label immigrants as “them” predisposes people to believe reports of law-breaking, dole-taking, and job-wrecking.

- The United States is perceived as a zero-sum society in which benefits to one group automatically subtract from another. The jobs that go to immigrants are not perceived to grow the society, but rather to drain the system of benefits that could go to native-born workers.

- Americans are fatalistic about the world in general but even more so about the contemporary effects of immigration. Immigration is seen as a sudden “surge,” not a regularly occurring chapter in the history of world migration. The system of administration, when thought about at all, is assumed to be broken, corrupt, and beyond remedy—part of “the government.”

- When asked to think specifically about the immigration system, most Americans have little to offer. The system is a “black box” in which people must learn English, say the Pledge of Allegiance, and possibly undergo a background check; few Americans articulate a more in-depth understanding of how the system works.

- Americans do tell an “us” narrative in which they readily embrace the idea of a nation of immigrants. But this story relies on the immigrants of today resembling those of the past. Islamophobia, terrorism, and economic insecurity all conspire to paint today’s immigrants as “not like our grandparents.”

The “us” reform narrative is undermined by the coherence with which the dominant models are assembled and, by contrast, the fragmentation of the alternative story. In an analysis of 300 materials drawn from 90 leading immigration groups, FrameWorks researchers found that the Restrictive/Punitive narrative7 consistently included logically linked American values plus causes of the problems and solutions. The Moral/Expansive narrative8 had numerous narrative holes: no causes, few solutions.9 In sum, the Restrictive/Punitive story—the essence of today’s cultural product on immigration—is advantaged by both content and form.

Far from “breaking our audiences’ guessing machines,” immigration advocates in our sample were trying to argue people out of them. Often attempting to “prove worthiness” by painting individual portraits of immigrants or by asserting that young immigrants arrived through no fault of their own, the stories being told only reinforce the dominant narratives.

BREAK THEIR GUESSING MACHINES

The most important work that immigration reform advocates must do is to disrupt the Them narrative and establish an Us story. This is the reframing prerequisite. Again, our research practice provides the fuel to spark the engine. While much of the “swamp” of cultural models works against progressive thinking, if activated, there are also important cognitive assets that can be recruited and fed. The very same people that contend that immigrants are largely law-breakers and job-takers can argue with equal vehemence that Americans should show respect for all people and celebrate diversity. People move seamlessly from one way of thinking to another, depending upon the cultural model that is activated or primed. Opinion is frame-dependent.

When we take another look at the Swamp of Immigration, we find a strong cluster of “Us” thinking that can be recruited. In subsequent testing, FrameWorks refined the priming of this humanistic cultural model as follows: “We need to treat everyone with the compassion they deserve as human beings. No matter where they were born, all people are entitled to the same basic respect.”

When reminded of our shared humanity, Americans became significantly more supportive of a path to citizenship, a liberalized visa system, and the use of social services to integrate immigrants into American life. They become more likely to see immigrants as a boost to the economy rather than a burden, and they become less supportive of deportation and inhumane treatment of immigrants. Importantly, when this moral appeal was framed as “rights,” it lost its positive effects on many policies. Similarly, the pragmatism many Americans expressed in the cultural models interviews also proved evocative and potent. When reminded of immigrants’ contributions to society, people remembered that immigrants contribute skills and spur economic growth rather than depressing it. Both nudges served to break people’s guessing machines in ways that opened them to a deeper and richer conversation about fixing the immigration system in ways more consistent with the expert view.

REFINE THEIR MACHINES

But now what? Still lurking in the Swamp of Immigration is the “black box”—the lack of understanding most Americans have about how the immigration system works. Most Americans struggle to imagine any immigration system at all, let alone the complex set of laws and policies that make the current system dysfunctional. Cognitive holes like this are opportunities to explain how systems and processes work through explanatory metaphors—simple, concrete, and memorable comparisons that draw on people’s everyday knowledge of how the world works.

FrameWorks researchers developed a “job description” for an immigration metaphor and then tested six candidates to see if they could boost people’s knowledge and attitudes about an improved system. One metaphor—the Sail—demonstrated statistically significant impacts on multiple measures. Here’s what this metaphor looks like: “Immigration is the wind in our country’s sails. It’s the labor, skills, and ideas that move our country forward. Right now, our sails are poorly positioned, and our policies are letting valuable wind power go to waste. When we fix immigration policies, all of our wind power can be used to move our country forward.”

When exposed to this metaphor, people were more likely to agree that immigrants contribute important skills to our society, that we need a flexible immigration system, that the system will grow the economy, and that the problem with the current system is that undocumented people can’t fully contribute. The Sail metaphor got everyone into the boat, further overcoming “us vs. them” reasoning.

If we want better policy conversations on immigration, or any social issue, we need to use an instruction manual and assemble our communications strategy in an orderly fashion. Only then can we understand how the opposition is driving the discourse and what we can do to change direction. Chip and Dan Heath offer one well-supported roadmap to guide our efforts; FrameWorks’ original research lets us run our strategy on all cylinders.

Want to learn more about reframing immigration? Access FrameWorks’ MessageMemo, Communications Toolkit, and FrameWorks Academy online course.

Notes

- Said, E. (2000). Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Heath, C. & Heath, D. (2007). Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die. New York: Random House.

- Baran, M., Kendall-Taylor, N., Lindland, E., O’Neil, M. & Haydon, A. (2014). Getting to “We”: Mapping the Gaps between Expert and Public Understandings of Immigration and Immigration Reform. Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute.

- Ibid.

- See for reference FrameWorks Academy’s online course on framing fundamentals.

- For fuller explanations of cultural models in the Swamp of Immigration, see Getting to “We”: Mapping the Gaps between Expert and Public and Understandings of Immigration and Immigration Reform and Finish the Story on Immigration Reform: A FrameWorks MessageMemo.

- In this story, immigrants are routinely portrayed as taking jobs away, and enhanced border patrols and restricted visas are seen as necessary to protect American workers.

- In this story, current US immigration policy is typically portrayed as ill-aligned with economic needs and a path to citizenship is required to advance economic development.

- O’Neil, M., Simon, A. & Haydon, A. (2014). Stories Matter: Field Frame Analysis on Immigration Reform. Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute.