This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s winter 2017 edition, “Advancing Critical Conversations: How to Get There from Here.”

In “Social Entrepreneurship’s All-American Mind Trap,” published in the Nonprofit Quarterly’s summer 2017 issue, Fredrik Andersson and Ruth McCambridge explore how this type of social-purpose initiative is “being imaged and defined as an act primarily of an individual rather than a collective.”1 The authors present and support several cogent claims that call into question the extent to which such “Lone Ranger” entrepreneurship is the prevailing type and, most significantly, whether or not it is as suitable as collective entrepreneurship to successfully address the most “wicked,” perplexing problems our society and the world face—including “poverty, hunger, racism, and environmental deprivation.”2 In this article, I elaborate on three of Andersson’s and McCambridge’s assertions: (1) the necessity for employing what they call “collective entrepreneurship”; (2) the necessity of large, cross-sector collaborations and other collective initiatives that align public policy, financial resource, and comprehensive services components to tackle “wicked problems,” instead of initiatives launched by an individual entrepreneur; and (3) that “wicked problems” are inherently public issues—namely, that they are highly contentious topics affecting a broad population in a given jurisdiction about which there are multiple, deep-seated, conflicting stakeholder interests and perspectives. Understanding them simply as “social problems” for which there are “innovative solutions” is a fundamentally insufficient framework.

Collective Entrepreneurship

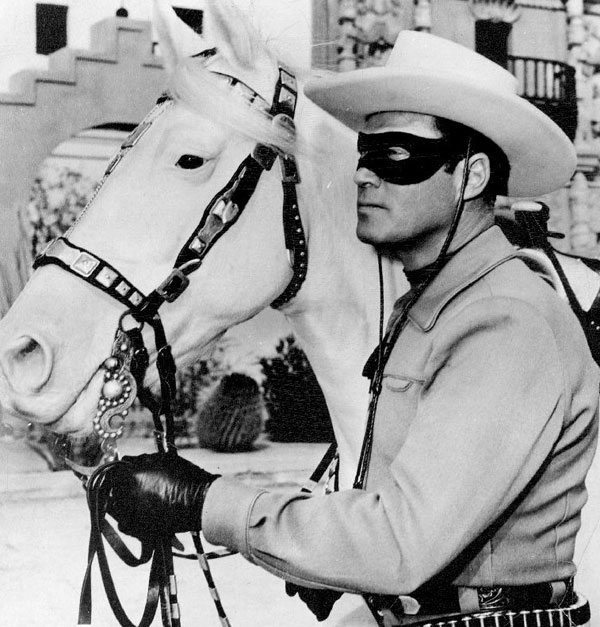

Andersson and McCambridge contrast “individual” with “collective” social entrepreneurship, stating that they represent two “warring frameworks” for understanding social change and innovation in American culture. The former they label the “Lone Ranger story,” which is insistent and deeply embedded in our nation’s cultural mythology. The latter they label the “community will narrative,” and describe the power and necessity of a committed group with “multiple anchors of commitment informed by multiple points of view and streams of information” to bring about effective, sustainable social change in our complex world.3

Indeed, collective entrepreneurship entails action beyond a committed group to more complex networks, coalitions, and collaborations composed of multiple stakeholder interests and groups. The necessity for this kind of effort and the distinctive leadership mind-sets and repertoire of skills that collective entrepreneurship requires are long established in various strands of academic and practice literature on social change, especially when it comes to addressing wicked problems. They compose a rich body of “lessons learned.” Had we heeded these lessons, many recent or current approaches to tackling wicked problems, such as the collective impact movement, likely would have avoided a good deal of early, exasperating effort when putting the ideas into concrete practice. To their credit, leading authors of that movement, such as John Kania and Mark Kramer, have over time expanded their understanding of the leadership attributes and collective strategies needed for collective impact to succeed, including recognizing—as many decades of study already had—that it is an “emergent” process and requires the participation of a very broad, inclusive range of stakeholders and voices across a community’s sectors and social strata.4

In fact, there is a long history in this sector of collective action aided by many decades-old practices of community/adult education and community development (as the concept was originally understood), incorporating collectively generated and pursued action to make a community stronger and more resilient. The United Nations, for instance, defines community development as “A process where community members come together to take collective action and generate solutions to common problems.”5

In 1994, in their book Collaborative Leadership, David Crislip and Carl Larson elaborated the distinctive mind-sets and skills needed for collaborative leadership. To highlight some of its features, it was the most suitable style when faced with a situation in which: (1) there is no single, predetermined group objective; (2) the problem or issue the collective is addressing cannot be identified in advance—nor can its solution be known, but “must emerge from the interaction of the stakeholders”; and (3) no single or few areas of expertise can be applied. Then, the leadership task is to: (1) convene and catalyze others to cocreate visions and solve problems; (2) convince people something can be done, not tell them what to do; (3) build stakeholder confidence in the process by cultivating relationships that build mutual trust and respect and are participatory and inclusive; (4) forgo exercising power from a position in a hierarchical structure, relying instead on one’s “credibility, integrity, and ability to focus on [and sustain] the process”; and, finally, (5) be a peer, a cocreator of possible solutions, not the superior expert. In short, they described many of the characteristics of situations we face when attempting to bring about truly significant social change, as well as several of the leadership tasks that must be performed in these situations.6

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

What Is Required to Tackle Wicked Problems?

Andersson and McCambridge stress that collective—not Lone Ranger—leadership is necessary to address wicked problems (drawing on the earliest definitions of the term by Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in their 1973 article, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning”). Rittel and Webber defined wicked problems as “issues with innumerable causes—problems that are tough to fully comprehend or define, and that don’t have a single and/or correct answer.”7 Such problems differ from “ordinary” problems in four characteristics, including not “being self-contained but entwined with other problems without a single, root cause,” and involving many stakeholders “who all will have different ideas about what the problem really is and what its causes are.”8

Going beyond their view, I propose that problems are best understood not as a binary choice between “ordinary” and “wicked” but rather as a continuum stretching from the simplest, most self-contained to the most wicked and complex. For those problems that are very wicked, they are best understood and addressed not through a problem-solving framework but a public-issues one. Understanding and acting upon wicked problems solely from a problem-solving framework—as if through discussions among multiple stakeholders a single definition of the problem can be determined and “innovative,” “data-driven” solutions can be discovered—is self-defeating. Public issues entail matters important to a large part of the population in a given political jurisdiction about which there are multiple, deep-seated, and conflicting interests, stakeholder understandings, and proposed answers. They are “issues” because they are highly contentious. Affordable quality healthcare for all is but one contemporary example. Public opinion is deeply divided about whether or not “all” have the right to such care, and how much people of different levels of wealth or income should pay for it. Furthermore, there is a blossoming variety of public-sector, business, health-professional and industry, insurance, citizen, consumer, nonprofit, philanthropic, and religious interests with differing viewpoints—and, in some cases, solutions—to propose. Of course, understanding the issues and evaluating different proposed approaches need to be based on robust data, evidence-based practices, and highly competent policy analysis—but these are just a few of the essential ingredients, beyond the ingredient of the will of those affected.

Therefore, large, cross-sector, multistakeholder collaborations and other collective efforts are required to tackle wicked problems—not just good teamwork among a comparatively small group of organizations—no matter how much diversity is represented with respect to skills, perspectives, and community experience. Whether attempting to revitalize underserved, disinvested, low-income communities or attempting to achieve affordable quality education or healthcare for those who lack such opportunities, a very wide range of assets, resources, perspectives, talents, and knowledge from diverse sectors, races, genders, classes, and so on must be brought to bear. These efforts need to take place at many levels of analysis and action, bringing together a multitude of leaders at the grassroots and grasstops levels and all social strata in between. Concurrent, aligned action on public policy, funding, and comprehensive services is required. This is exceedingly difficult, painfully slow, complex work that requires a very long commitment.

This is also work that requires incredible collective persistence and resilience in the face of fierce headwinds. Why? Because when changes in public policy and financial resource allocation are necessary (in addition to services) for a given population or community, proposed strategies and solutions must entail some degree of redistributed resources and opportunity. This means the effort is likely to be resisted by well-entrenched interests. Success will entail mobilizing political action and may require engaging social movements as well as more traditional, institutionalized collective enterprises.

…

Having for several years advised and/or observed collective initiatives addressing wicked problems such as racial inequity and underserved, disinvested communities—in addition to participating over five decades in national social movements—it is clear to me that collective, collaborative leadership among a very inclusive multitude of stakeholders, and not a “hero” social entrepreneur, is what is necessary for substantial social change. And the members of the collective leadership must demonstrate authentic, persistent effort to understand the lived experiences and perspectives of a wide array of individuals and groups—particularly those whose experiences and circumstances are most dissimilar to their own—when working on a shared issue.9 Finally, and perhaps most disappointing to those who might wish otherwise, a redistribution of power or resources of any kind—when there are vested interests currently commanding a large portion of those resources—likely will never occur without conflict. Therefore, whatever is perceived to be “heroic” action by some may well be viewed as the opposite by others. To exercise leadership in such situations, often people must pick sides.

Notes

- Fredrik O. Andersson and Ruth McCambridge, “Social Entrepreneurship’s All-American Mind Trap,” Nonprofit Quarterly 24, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 28.

- Ibid., 30–31.

- Ibid.

- Their updated statement of practice principles has expanded to include several that this earlier literature suggested, such as engaging people as full participants from the communities and populations the initiative seeks to serve; recruiting and cocreating with cross-sector partners; and building a culture that fosters relationships, trust, and respect across participants. For more on this, see Tamarack Institute; The Latest; “Collective Impact Principles of Practice,” blog entry by Devon Kerslake, June 3, 2016.

- UNTERM: The United Nations Terminology Database, “Community Development.”

- David D. Crislip and Carl E. Larson, Collaborative Leadership: How Citizens and Civic Leaders Can Make a Difference (Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass, 1994). For a comprehensive review of the literature from that period on collaboration and what factors foster or hamper its success, see the meta-analysis of an original sample of 133 studies by Paul W. Mattessich and Barbara Monsey, Collaboration: What Makes It Work (St. Paul, MN: Amherst H. Wilder Foundation, 1992).

- Horst W. J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4, no. 2 (June 1973): 155–69.

- Ibid.

- These observations include the author’s work with the following major collective initiatives in the St. Louis bi-state metropolitan area: Community Builders Network of Metro St. Louis; Social Innovation St. Louis; Interfaith Partnership of Greater St. Louis; Ready by 21; and East Side Aligned. They are also based on participation and occasional modest leadership in the civil rights, antiwar, women’s, and other social justice movements over five decades.