March 22, 2018; Next City

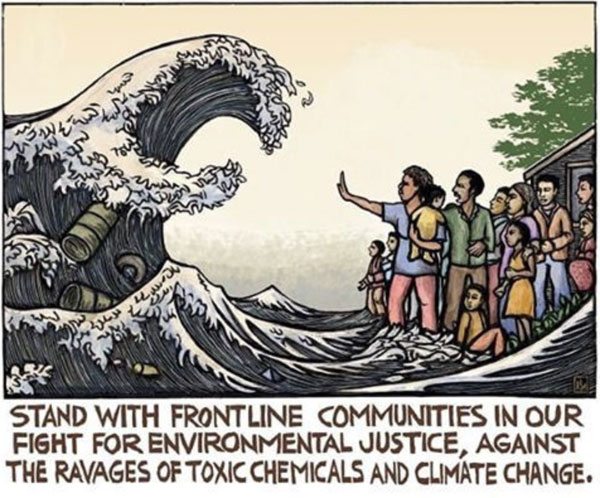

For nonprofit organizations concerned about equity, environmental justice is a critical lens to consider. In fact, environmental justice stands squarely at the intersection of community and economic development, environmentalism, and systemic inequality by addressing the structural components of racism that negatively and disproportionately impact the health of communities of color.

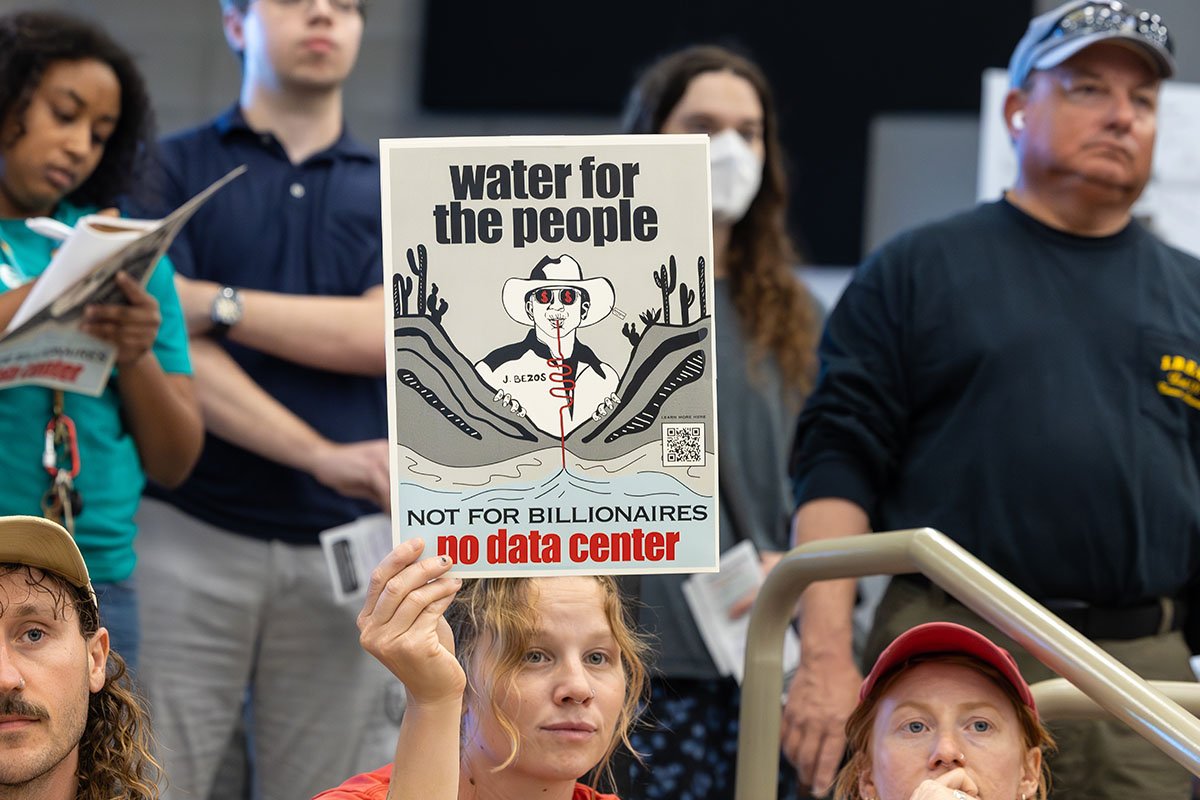

The scope of environmental racism has come into the public awareness recently, with high profile cases like the water crisis in Flint and the Keystone XL Pipeline dramatically highlighting the consequences and implications of environmental racism on communities of color. As a result of increased public awareness and the reality of entrenched environmental racism as a driving force in society, a vibrant environmental justice movement has crystalized. Comprising public entities, nonprofits, businesses, and the philanthropic sector, it seeks to transform the systems that contribute to environmental inequality. One of the central themes of the environmental justice movement is that the integrity and well-being of communities should not be compromised in the face of and in the name of economic progress. While economic prosperity is certainly a priority, community health and well-being is equally important.

These themes came into focus last week in Birmingham, Alabama, where the city council voted to deny a license to a scrap metal recycling facility, Jordan Industrial Services, largely because of grassroots and community resistance. The business sought to open a metal recycling facility in northern Birmingham, a predominantly African American working-class area, and tried to sell the project as one that would create jobs. The community opposed this because of the well-documented impacts that recycling metal has on communities. One of the main byproducts of cutting and welding metal is hexavalent chromium (or Chrome IV), which is released into the air and causes a range of health issues. In fact, the Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) says that hexavalent chromium “is known to cause cancer. In addition, it targets the respiratory system, kidneys, liver, skin and eyes,” while the National Toxicology Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences states that “studies have consistently shown increased lung cancer rates in workers who were exposed to high levels of chromium in workroom air.” This victory in Birmingham illustrates how the environmental justice movement has gained influence, and used traditional political pathways and engagement as a core strategy, and with good reason.

The need for engagement in the political process as it relates to environmental justice has never been higher. According to a 2016 report by the Center for Effective Government (CEG) entitled “Living in the Shadow of Danger: Poverty, Race, and Unequal Chemical Facility Hazards,” there are more than 12,500 facilities throughout the country that store chemicals dangerous enough to require a Risk Management Plan (RMP) to be submitted to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Nearly 23 million people live within one mile of an RMP facility, and of these, nearly half are people of color. One in 10 schoolchildren in the United States attend one of the 12,000 schools located within one mile of a RMP facility, and almost two-thirds of children that live within one mile of a high-risk chemical facility are children of color.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While these statistics are startling, the impact of chemical pollution may in fact get worse. The EPA has come under scrutiny recently for rewriting a rule that makes it more difficult to track, and hence regulate, health consequences of chemicals. This was among many rule changes sought by Dr. Nancy Beck, a former executive at the American Chemistry Council, the chemical industry’s main trade association, who was appointed as the Deputy Assistant Director for the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution last year. Given that the EPA oversees roughly 80,000 chemicals and regulates how those chemicals intersect with communities, changes such as this illustrate how private interests jeopardize public safety and provides an opportunity for ongoing public engagement.

While the CEG report concerns RMP facilities, trends of environmental racism cut across environmental issues. Last month, the EPA’s National Center for Environmental Assessment released a study on disparities in the location of particulate matter, and found those in poverty had 1.35 times higher burden than did the overall population, and non-Whites had 1.28 times higher burden. Blacks, specifically, had 1.54 times higher burden than did the overall population. In another instance, as NPQ recently reported, the EPA recently dismissed a civil rights case in Uniontown, AL where residents filed a complaint under Title VI of the Civils Rights Act regarding Arrowhead landfill, where waste from 33 states, including over four million tons of coal ash, has led to health concerns in the overwhelmingly African American community.

Unfortunately, progress by the EPA regarding environmental justice has been inconsistent. While the agency has developed an Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool for visualizing the impacts of pollution, it has struggled to comprehensively address environmental justice, especially as it relates to civil rights. According to the US Commission on Civil Rights’ 2016 report, “Environmental Justice: Examining the Environmental Protection Agency’s Compliance and Enforcement of Title VI and Executive Order 12,898,” the EPA “has a history of being unable to meet its regulatory deadlines and experiences extreme delays in responding to Title VI complaints in the area of environmental justice.” In fact, as of the publishing of the report, the agency had never made a formal finding of discrimination. For context, Executive Order 12898—Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations—was issued by President Clinton in 1994.

While these reports and developments illustrate significant challenges, the environmental justice movement is determined to shift these systemic realities, and nonprofits, as always, are playing a critical role. In September, New Jersey Senator Corey Booker introduced the Environmental Justice Act of 2017, a bold bill supported by several local, regional, and national nonprofits. The bill seeks to strengthen the federal response and participation in environmental justice by codifying and expanding Executive Order 12,898, as well as requiring agencies to implement and update annually a strategy to address negative environmental and health impacts on communities of color, indigenous communities, and low-income communities. This represents forward thinking and is an example of how government should work in partnership with communities. For nonprofits, the path to equity must include environmental justice, and engaging in the public arena to advocate for changes is a necessary part of that collective journey.—Derrick Rhayn