March 26, 2018; Huffington Post, “Proof Points” and the Associated Press

Education is seen as a key element in addressing the economic and social challenges so many Americans face. Much of the national debate has focused on how best to make changes to our system of public education. How much should we rely on market forces and parental choice to drive improvement? Should we replace much the traditional framework with privately run charter schools or by giving public funding directly to each parent in the form of vouchers? Less attention has been paid to how much we spend on education and what it costs to provide the education we wish for our children.

A new effort from a Rutgers University team provides a new perspective on educational spending and success that can guide local, state, and national policy makers. Using data sets that compared local district educational outcomes and spending, The Real Shame of the Nation: The Causes and Consequences of Interstate Inequity in Public School Investments set as its goal determining what it costs to educate a child to reach an average level of educational performance.

The Rutgers researchers found that “it can cost anywhere between roughly $5,000 and $30,000 a year per student in order to hit average test scores.”

Two factors mainly determine where a district lies along that range: location and mix of students. Some school districts bear higher costs because they’re located in expensive regions where salaries, including those of teachers, are high. Population density matters too. The costs of educating poor children escalate faster in urban areas.

Not surprisingly, the study shows that the cost of reaching an average level of outcomes is more challenging for districts that serve large numbers of low-income students, since of course greater intervention per pupil is required to overcome the many obstacles to education that poverty brings. As a result, the report authors explain, “It costs more than three times the amount per pupil ($20k to $30k) to achieve national average outcome goals in very high poverty districts (>40 percent poverty) as it does in relatively low poverty districts (<10 percent poverty) ($5k to $10k).”

Equal funding for unequal levels of required educational intervention results in far from equitable outcomes. As the report indicates:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

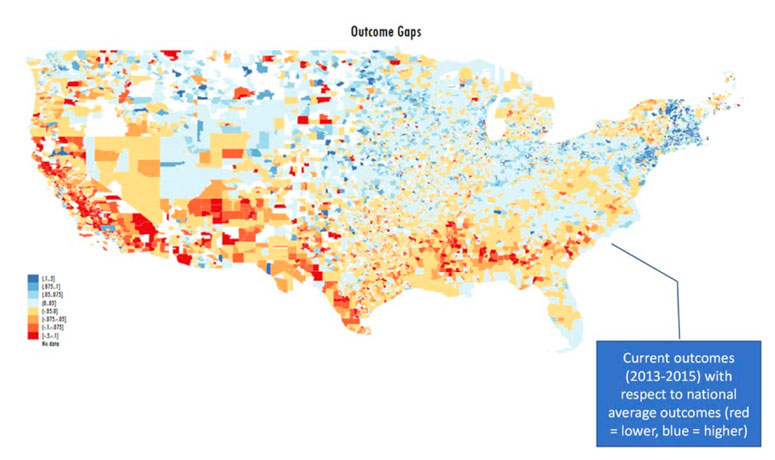

High-poverty school districts in several states fall thousands to tens of thousands of dollars short, per pupil, of funding required to reach the relatively modest goal of current national average student performance outcomes on standardized assessments. In some states—notably Arizona, Mississippi, Alabama and California—the highest poverty school districts fall as much as $14,000 to $16,000 per pupil below necessary spending levels.

A separate look at the school funding commissioned by the Kansas legislature painted a similar picture of the need for more educational funding. According to the Associated Press:

Improving Kansas’ public schools could cost the state as much as $2 billion more a year, depending on its ambitions for boosting student performance, according to a new report Friday that reset the Legislature’s education funding debate…. The report outlined three scenarios for improving student performance, and the least expensive would cost $451 million more a year, an increase of about 10 percent. The most ambitious option—boosting the graduation rate and vastly improving student scores on standardized tests—would result in the $2 billion increase. “This is talking about very big numbers to get to very big increases in student achievement,” said Kansas Association of School Boards lobbyist Mark Tallman. “If you want a lot better results, there’s a cost.”

There are other factors beyond spending that affect educational outcomes and will be difficult to overcome. Matt Chingas, a school finance expert at the Urban Institute, told the Huffington Post that “teacher quality is one of the most important factors in influencing student achievement. Because of low teacher salaries in Arizona, the state might not attract the best teachers it could. If the state were to suddenly start spending more, and use that money to give teachers raises, then, initially, the state would just be paying the same set of teachers more. Student achievement probably wouldn’t budge much. It could take 30 years for the current teachers to retire and be replaced with a higher quality teaching force.” Yet, the study concludes that funding matters and too many districts, many with the most changing students, remain underfunded.

State policymakers are struggling with the politics of creating funding systems that target funds to districts with the greatest challenges. Finding new funding raises the specter of higher taxes, often based on regressive property tax systems; what’s needed are revised formulas that risk asking some districts to take a smaller share of school funding so needier districts can be brought up to par. The authors of the Rutgers study see the solution coming from national effort:

Even with relatively high effort, some states simply lack the capacity to close the gaps we have identified. These interstate variations speak to the need for a new and enhanced federal role in improving interstate inequality in order to advance our national interest in improved education outcomes across states. Our empirical model shows that federal funding for schools has been insufficient for improving interstate inequality. Arguably, the interstate gaps we have presented strike at the core of our national interest and call for urgent federal action.

The bottom line, of course, is that while education is a vital tool, using education as a pathway out of poverty is a very expensive proposition. Clearly, our nation faces a tough challenge. To address the obvious gaps, nonprofit advocates will need to boost advocacy efforts both for adequate education funding in low-income districts and for greater social service supports that might make the education hill that we ask teachers and others to climb a little less steep.—Martin Levine