Last month, HUD awarded Puerto Rico almost $18.5 billion as part of a $28 billion package for major disasters since 2015 for both recovery and mitigation. As the press release notes, “The grants announced today represent the largest single amount of disaster recovery assistance in HUD’s history.” (However, total federal aid to Puerto Rico falls far short of the $114.5 million in federal aid for Katrina or the $56 billion for Sandy). Secretary Ben Carson, in a moment of apparent lucidity, says, “It’s clear that a number of states and local communities are still struggling to recover from a variety of natural disasters that occurred in the past three years.” The money will need to address the particular long-term challenges on the island. Many are seeing this effort as a potential model for future extreme weather scenarios.

Hurricane Maria destroyed about 90,000 homes in Puerto Rico, shut down the electrical grid, and forced more than 300,000 people out of the island. But it is the island’s longstanding colonial relationship with the US and the concomitant extractive economy, which began collapsing about a decade ago and finally succumbed to Maria, that is hamstringing Puerto Rico.

The HUD package targets South Carolina, Texas, Florida, West Virginia, North Carolina, Louisiana, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Missouri, Georgia, and California. The funds will be given out through HUD’s Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program, which allows the money to be used for damaged housing, businesses, and infrastructure. HUD awarded $1.5 billion to Puerto Rico in February, also through CDBG. According to National Public Radio’s Adrian Florido, the combined almost $20 billion from HUD is twice the size of Puerto Rico’s annual general fund revenues.

Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit that provides capital and development services for affordable housing and community revitalization, is a key partner in Puerto Rico’s recovery. On April 26 it hosted “The State of Housing Response & Recovery in Puerto Rico Following Hurricane Maria,” which Laurie Schoeman, Enterprise’s Senior Program Director for the national resilience initiative, told NPQ is “the most comprehensive think tank to be created on this topic.”

Schoeman oversees Enterprise’s resilience and recovery efforts across the US and says, “There are many hot spots. Puerto Rico is a major one.” She continues, “What I see is that, more likely than not, communities don’t always have the tools they need to prepare for climate risk or recover, so we’re working hard to help with that.”

Enterprise’s support includes toolkits like the Green Capital Needs Assessment Protocol, which helps property owners and underwriters conduct holistic assessments that maximize their energy and water use during capital improvements. The Strategies for Multifamily Building Resilience, which offers 19 practical strategies for mitigating and adapting to extreme weather risks, was developed for New York after Hurricane Sandy. It also provides flooding counseling in New York City and delivers trainings. Schoeman says, “We are bringing all of this to bear in Puerto Rico.”

Marion McFadden, Enterprise’s Vice President for Public Policy, highlights in the aforementioned Puerto Rico think tank convening that the $20 billion from HUD is “the biggest award ever,” and contrasts it to the $5 billion each awarded for Hurricane Sandy and Hurricane Katrina.

In describing how these awards are decided, she tells NPQ,

It’s a mix of art and science how HUD makes those funds available, or Congress makes those funds available. There’s no permanent program for disaster recovery. The CDBG only exists when Congress decides it’s appropriate to make an appropriation. HUD is intended to fill the gap left behind from other programs, like FEMA. Congress compares across disasters, to do an apples-to-apples assessment of damages, and then awards those funds. They don’t include the variables initially, but then they publish them in the Federal Register.

The processes available for communities recovering from disasters are tiered by timing and income eligibility. First, people with insurance can tap into their policies. Then, FEMA steps in to help citizens and first responders cover uninsured losses, but it has a cap of $33,000 and McFadden notes that, “by the time people pay for temporary rental and other costs, it’s not enough to do any recovery repairs.”

After that, the Small Business Administration makes small business loans available post-disaster with below-market rates. They also have a homeowner’s loan program. However, they only make loans available to creditworthy applicants, so, according to McFadden, it has a high decline rate. She also notes, “For families who are doing well, who can afford an additional payment, it’s great because they can get it quickly. It is available much faster than HUD grants.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Finally, eventually, HUD money may become available, like is happening now. HUD money is for long-term recovery. HUD pushes the money from Congress to the commonwealth, so the governor in Puerto Rico’s case is responsible for ensuring that there is a public participation process with time and space for comments. The commonwealth then submits the final plan for HUD approval. Then there’s the designing and operating of the program. According to McFadden, in other jurisdictions it has taken 18 months to two years before homeowners start to get money. In Puerto Rico, Governor Rosselló must submit the plan by August 8th.

It’s up to the governor to set policies about how much money people can get, but HUD has predetermined that to qualify for housing, people must earn no more than 120 percent of the area median income, so high-income people are not going to be able to get those grants. McFadden says, “This is a new policy, a Trump policy. I think it was informed by Sandy, when New York and New Jersey approached recovery very differently. In New Jersey, HUD assistance for homeowners was capped at $150,000, and it was available for people earning up to $250,000 income a year. In New York, there was no cap on total family income or the amount. There was a caveat; they didn’t identify a total cap, a dollar amount, but New York state would only give money for non-luxury renovations.”

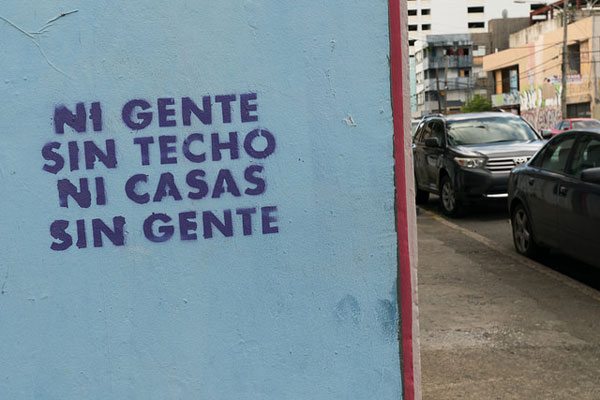

An issue on the island is self-built housing, or informal housing, which is a global issue related to poverty and variably defined, but a simple definition is housing that is built without pulling permits or following code. HUD money can be used for practically anything related to recovery, including giving people title to their properties. This is significant. As Florido notes, “More than half of Puerto Ricans don’t have title to their properties. That’s why FEMA has denied so many of them grants for home repair, which is why there are still so many people living in damaged homes on the island.” This will also help after the next storm.

Enterprise has been working in Puerto Rico for the last 10 years providing technical assistance to the commonwealth in the development of its state housing plan, providing capacity building for nonprofits, and investing in low-income housing. For this effort, it will partner with the Puerto Rico Builders’ Association, the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Architecture and School of Planning, the Puerto Rico Housing Department, Álvarez-Diaz & Villalón (an architecture and interior design firm), Perkins + Will (a global sustainable design firm), and MIT’s Urban Risk Lab to develop Strategies for Puerto Rico Housing Resilience, a practical design-and-construction guide that will be distributed at no cost, along with trainings in English and Spanish, to help minimize and reverse Maria-related housing damage in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands.

Schoeman says, “This guide will be developed by and for Puerto Rico. That’s very important. It has to be created according to best practices and the vernacular of the island.” Therefore, it will address self-built housing.

In response to questions from NPQ about the impact on this process of the lack of trust of many Puerto Ricans in the governor and how this process will coordinate with the many other local planning processes, Erika Ruiz, director of Enterprise Advisors, says, “I’ll be honest, we’re hearing the same thing…There are different planning processes and we’re trying to assist the governor to make sure these things are considered…There is lots of thought leadership about how to move forward. There could be more inclusivity in these process and planning activities. They don’t always get to everyone or offer a space to include everyone.”

McFadden says, “In part that’s why we did the convening, because we know that philanthropy has tried to bring together some of the best minds to work on recovery. We hosted an event to bring leaders from around the island together that don’t always come together.”

Ruiz says, “The thing about the nonprofit community that stood out to me is how much in the trenches they are and how they rose to the occasion. They’re a very important voice in this process. There’s still some work to be done to make sure those voices are involved in design of policies and programs. The community groups do a great job, but they’re also small and under-resourced.”

McFadden points to an issue that has not received much attention. She tells NPQ:

Here’s something that’s not on the radar: How are the people who are not living in Puerto Rico legally going to be assisted? I don’t mean informal housing. I mean people from the Dominican Republic or other places who have not applied to FEMA and are unlikely to receive federal dollars, who are essential parts of the community. There is a great need here for philanthropic assistance. The issue keeps coming up as we talk to community organizations. There are illegal immigration–based fears.

There is lots to learn in this effort about how best to serve the people of Puerto Rico. For decades, they have done what they have had to do to make things work, including building houses without permits. In Hawaii, housing policy efforts have had to address native beliefs that support stewardship of collectively shared land even though that question is highly contested. Similarly, in Puerto Rico, long-term recovery efforts will have to address the lived realities that have resulted from over 100 years of subordination to the US, a local government that has often served US business interests, and economic policies that have led to large-scale poverty. When almost half of the people live in informal housing, one has to ask, “What are the systems that support this?” We will see how far this effort goes to shift the tide. However, while private home ownership may help in a Western-based world view, perhaps it’s also time to make room for the growing commons, which is how people are getting by in the meantime.