May 22, 2018; The Conversation

We probably should not be surprised that an industry has been built to support “rounding down” the wages of low paid workers, but there’s evidently a large market for it. Perhaps United Way’s new ALICE initiative should pay attention to this kind of corporate behavior.

It’s all pretty simple. You clock into your job, and the system is set to round the time up or down (sometimes in your favor, sometimes not) if you are a few minutes early or you stay late. The system is set to deduct time for your breaks and your lunch, even if you are not able to take that time because of a crisis or a demanding work project. You don’t get paid for that time worked. And now we know that companies are deducting these hours purposefully.

University of Oregon Associate Professor of Law Elizabeth C. Tippett documented this first and co-authored a 2017 study on timekeeping software and a follow-up article on wage theft. Now, she writes in The Conversation about how employers are using software for the purpose of “wage theft” and are cheating workers out of millions of dollars of wages they have worked and should have been paid for.

“Wage theft” is a shorthand term that refers to situations in which someone isn’t paid for the work. In its simplest form, it might consist of a manager instructing employees to work off the clock. Or a company refusing to pay for overtime hours.

A report from the Economic Policy Institute estimated that employees lose $15 billion to wage theft every year, more than all of the property crime in the United States put together.

That report, however, focused on workers being paid less than the federal or state minimum wage. Our 2017 study, which was based on promotional materials, employer policies and YouTube videos, suggested that companies can now use software to avoid paying all sorts of hourly workers.

Tippett focuses on two main areas of digital wage theft by employers: rounding and automatic break deduction. She did a search to see if there were legal cases brought to reclaim lost wages to these two causes, expecting to find only a few. To her surprise, she found hundreds and hundreds of legal opinions. To quote her from the article, “The study’s methodology does not support quantitative inferences about how often digital wage theft occurs or how much money US workers have lost to these practices over time. But what I can say is that this is not a theoretical problem. Real workers have lost real money to these practices.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

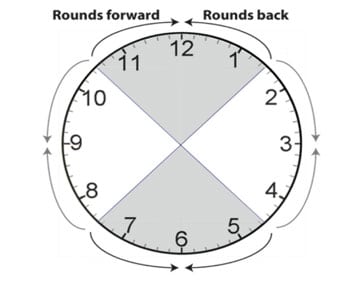

Rounding is almost like gambling; if you come to work too early, you lose wages, but if you are late, the same thing happens. You have to hit the “sweet spot” for the digital clock to add to your hours (mostly set in 15-minute increments, but not on quarter hours as one might think). This clock illustrates one such digital rounding plan.

Some companies prohibit workers from clocking in too early or too late, thus losing time worked.

With automatic break deductions, it is harder to regain time lost. The software does not know if you took your break or had a full lunchtime or not, so it always errs on the side of a full break. Then, it is your word against a machine.

In some workplaces, taking a lunch break can be difficult, especially for those providing patient care in hospitals and nursing homes. Studies of nurses suggest that they are completely unable to take breaks in about 10 percent of shifts and aren’t relieved of duty for meals and breaks in about 40 percent.

The author concludes that these issues exist due to outdated rules from “back in the day” when employers had to calculate wages by hand. The assumption was that things would average out over time. Automatic break deductions were not even in the picture when these regulations were at play, so courts now have to struggle to determine what is fair in this arena.

Then again, the courts may not get involved, given the Supreme Court ruling this past week that, under current law, all employee disputes may be settled by individual arbitration (see this NPQ article) and class action, which has been the path for much of the wage theft disputes. As Tippett concludes, “This problem is not going away. As long as these regulatory loopholes exist, employers and software makers will find ways to exploit them. That means if you’re paid an hourly wage, you may very well be losing out.”—Carole Levine