May 21, 2018; National Public Radio and Washington Post

Even as some corporations have been reconsidering their forced arbitration practices because they can blind them to abuses they consciously do not want to support, others have been anxiously awaiting a decision from a majority conservative US Supreme Court in hopes they can continue to avoid accountability. This latter group got busy last night communicating their “take it or leave it” positions on employment. The decision particularly affects groups of non-unionized workers with civil rights complaints—as in systematic discrimination. As in #MeToo.

Leah Fowler writes in Quartz that by “enabling companies to force arbitration, the Supreme Court is oppressing and silencing untold numbers of employees who experience workplace discrimination, especially sexual harassment.” She adds:

Coded as the decision may be, it’s a devastating blow to the #MeToo movement, and the fight for gender equality at work. Forced arbitration often comes along with non-disclosure agreements, which can prevent survivors of sexual harassment from publicly ousting their abusers or rallying public support for their cases. Mandatory arbitration clauses also often limit the amount that can be paid to employees who’ve experienced workplace discrimination.

The result, a clear setback for workers’ rights, says that employers can require workers to settle disputes through individual arbitration rather than class action or joining together to press a complaint against a company. The five-to-four decision is likely to have ramifications that are both immediate and long-term.

The ruling came in three cases—potentially involving tens of thousands of nonunion employees—brought against Ernst & Young LLP, Epic Systems Corp., and Murphy Oil USA Inc.

Each required its individual employees, as a condition of employment, to waive their rights to join a class-action suit. In all three cases, employees tried to sue together, maintaining that the amounts they could obtain in individual arbitration were dwarfed by the legal fees they would have to pay. Ginsburg’s dissent noted that a typical Ernst & Young employee would likely have to spend $200,000 to recover only about $1,900 in overtime pay.

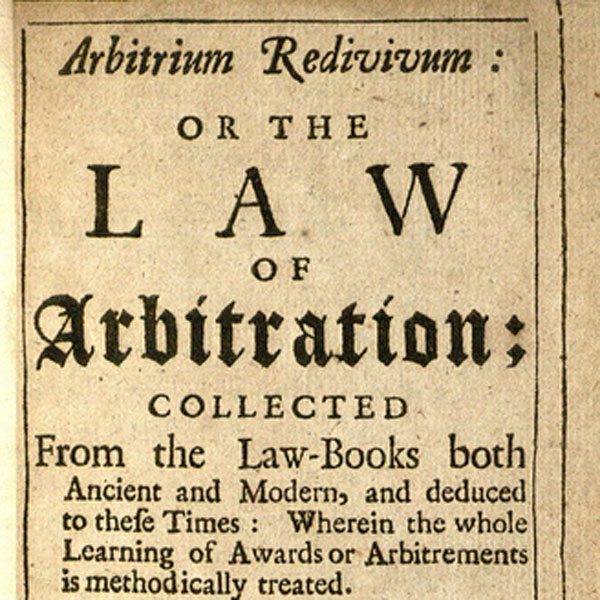

The employees contended that their right to collective action is guaranteed by the National Labor Relations Act. The employers countered that they are entitled to ban collective legal action under the Federal Arbitration Act, which was enacted in 1925 to reverse the judicial hostility to arbitration at the time.

There was a lot at stake in this case that reached beyond the issue of individual arbitration versus class-action lawsuits. In the era of the #MeToo movement, and as issues of workplace discrimination on the basis of race, class, and gender abound, employers have moved with great caution for fear of major lawsuits. With this ruling, those days may come to an end. As reported by Nina Totenberg of NPR, “There is no transparency in most binding arbitration agreements, and they often include nondisclosure provisions. What’s more, class actions deal with the expense and fear of retaliation problems of solo claims. As Ginsburg put it, ‘there’s safety in numbers.’”

The majority decision was written by Justice Neil Gorsuch and the dissent by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Both justices seem to lock horns frequently, and Gorsuch took the unusual option of adding a dissent to his decision to counter Ginsburg’s dissent. In stating the case for the majority, Gorsuch addressed the question of whether employers have the right to handle employee disputes on a case-by-case basis or if employees always have the option of bringing claims collectively. The Washington Post recounts:

“As a matter of policy these questions are surely debatable,” Gorsuch wrote. “But as a matter of law the answer is clear. In the Federal Arbitration Act, Congress has instructed federal courts to enforce arbitration agreements according to their terms—including terms providing for individualized proceedings.”

Workers had contended that another federal law, the National Labor Relations Act, makes illegal any contract that denies employees the right to engage in “concerted activities” for the purpose of “mutual aid and protection.” That means that some sort of collective action cannot be prohibited, the workers say.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

That was the thrust of a forceful dissent from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who called the decision “egregiously wrong” and underlined her objections by reading part of her dissent from the bench.

“The court today holds enforceable these arm-twisted, take-it-or-leave-it contracts—including the provisions requiring employees to litigate wage and hours claims only one-by-one,” she said. “Federal labor law does not countenance such isolation of employees.”

Trying to arbitrate such claims individually would be too expensive to be worth it, she wrote, and “the risks of employer retaliation would likely dissuade most workers from seeking redress alone.”

Within hours of the decision, some companies were preparing arbitration agreements and class-action waivers to go into employee materials. Other companies were sending emails to employees with arbitration agreements and notes that said if they continued to come to work, it would be assumed they accepted the agreement.

An amicus brief filed in the case by the ACLU and NAACP lays out the very real implications of this decision:

American democracy depends upon our unwavering commitment to equal opportunity. Federal labor law honors that commitment by guaranteeing employees the right to challenge workplace discrimination through concerted activity, including picketing, striking, and group adjudication of workplace rights. Yet mandatory pre-dispute arbitration agreements, which have become increasingly prevalent in the American workplace, now commonly prohibit employees from joining together in any combination and in any legal forum to vindicate their right to be free from workplace discrimination, and other core statutory rights. By barring every imaginable form of group legal challenge to an employer’s unlawful workplace practices—from simple joinder to consolidation of claims to collective and class actions—these contractual prohibitions pose a substantial threat to Congress’ longstanding goal of eradicating discrimination in the American workplace. Specifically, workers will be precluded from using certain core civil rights legal theories that have been crucial for securing equal opportunity in the workplace. For civil rights, the consequences of permitting unrestrained and ubiquitous use of arbitration clauses in individual employment agreements will be profound.

“Civil rights and class actions have an historic partnership.” Jack Greenberg, Civil Rights Class Actions: Procedural Means of Obtaining Substance, 39 Ariz. L. Rev. 575, 577 (1997). Landmark class actions and other forms of group litigation have long been essential components of our nation’s slow but deliberate progress toward a “more perfect Union.”

The brief is worth reading for the extent of the implications for civil liberties and to inform a reconsideration of movement strategies.

Elsewhere, of course, in Silicon Valley and Hollywood, where corporations have themselves been declaring their willingness to remove such arbitration agreements from their contracts, it will be interesting to watch whether they take cover in the decision or move forward to greater accountability.

Meanwhile, there is some legislative action in this area, albeit unlikely to move forward in a republican dominated congress. Nick Jack Pappas writes for Fast Company:

The likelihood of changing the law in favor of actual workers is slim to none while Republicans control the Senate, House, and Presidency, but if Democrats take back Congress in the upcoming midterms, those odds may improve dramatically. Indeed, there are already inklings of bipartisan support for reform: Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) has sponsored the Arbitration Fairness Act, and last year Senators Lindsay Graham (R-SC) and Kristen Gillibrand (D-NY) announced legislation to end forced arbitration pertaining to sexual harassment in the workplace.

Yet one more reason to get out the vote in the midterms.—Carole Levine and Ruth McCambridge