October 21, 2018; Last Real Indians

As NPQ has noted, Native American nations have long served as a US dumping ground when it comes to the environment. A ballot proposition in the state of Washington, however, could generate significant resources for climate resiliency in Indian Country. The ballot measure, called Initiative 1631, would raise $2.2 billion over the first five years—and ultimately $1 billion a year—for clean air, clean water, clean energy, and healthy communities.

Of this amount, according to the initiative text, “A minimum of ten percent of the total investments authorized under this chapter must be used for programs, activities, or projects formally supported by a resolution of an Indian tribe, with priority given to otherwise qualifying projects directly administered or proposed by an Indian tribe.”

As Matt Remle explains at Last Real Indians, the mechanism would be to place a $15 per metric ton fee on carbon dioxide emitted starting in 2020. The fee would then go up by $2 a metric ton per year (plus inflation adjustments) until Washington meets its 2035 goal of reducing its carbon footprint by 36 percent. By 2035, the fee is expected to rise to $55 per metric ton.

Why a fee and not a tax? Under state law, with a “fee,” the revenues collected cannot go into the state general fund. Instead, notes Robinson Meyer in the Atlantic, “Every cent raised by Initiative 1631 must go toward solving climate-related problems or protecting the state’s environment.” Priority areas include public transit, energy-efficiency upgrades, and renewable energy development. Meyer adds that, “One-quarter of its revenue must be spent to protect forests and streams in the state. One-twentieth must directly flow to communities that stand to be hurt by either climate change or the transition away from fossil fuels.”

Meyer adds that while the fee would be unique in the US, the neighboring province of British Columbia has taxed carbon for a decade, with the current amount about twice what is being proposed in Washington. Nationally, Canada’s government has a policy in place that would assess a C$50 a ton (US $38 a ton) tax on carbon nationally by 2022.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Washington’s carbon fee would give the state the nation’s strongest carbon laws in the US, save California. In California, the state has a “cap and trade” policy, which, rather than setting a straight fee encourages conservation by allocating carbon emissions credits to companies; those using less their allotment can make money by selling credits to those whose carbon emissions exceeds state standards. As NPQ has profiled, money raised in California through cap-and-trade has helped boost climate resiliency in low-income neighborhoods in Fresno and elsewhere.

So far, the “No” campaign has raised $22 million to oppose the initiative. Nearly all of that money comes from oil and gas companies, as an article in Vox details. Leading contributors to the “No” campaign” include Philipps 66 at $7.62 million, the refinery company Andeavor (now Marathon Petroleum) at $4.362 million, British Petroleum America $3.396 million, and British Petroleum $3 million, with another $2 million-plus from other industry companies.

In terms of what is at stake in Indian Country, Remle cites a 2016 report by the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission that details some of the leading threats, which include:

- Loss of water supplies for drinking and other needs due to saltwater intrusion from sea level rise, or changes to precipitation, streamflow, and/or groundwater availability.

- Declining populations of wildlife and birds due to habitat changes, loss of food sources, disease, and competition with invasive species.

- Negative societal outcomes from poor air quality, heat stress, spread of diseases, loss of nutrition from traditional foods, and loss of opportunities to engage in traditional cultural activities.

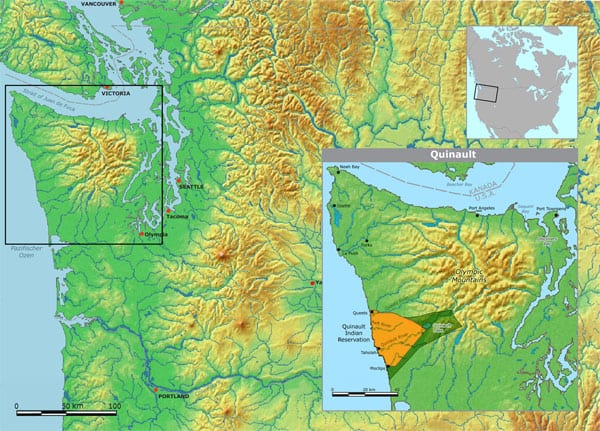

For example, Remle notes that the coastal Quinault Nation “is in the process of relocating an entire village of over 700 people uphill due to rising ocean levels.”

It is unclear whether the initiative will pass. A ballot measure that proposed to tax carbon in 2016 failed by an 18 percentage-point margin. However, the current measure has considerably more support than the 2016 measure did—in particular because the proposal outlines more clearly where the revenue raised would go.

For her part, Fawn Sharp, president of the Quinault, is optimistic. Speaking at a rally last month, Sharp said, “Once we take practical action other states are going to follow. This is a point in time where Washington state is going to make history.”—Steve Dubb