January 30, 2019; Teen Vogue

A little over 25 years ago, on January 1, 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the US, Canada, and Mexico came into effect. On this day, too, notes Andalusia Knoll in Teen Vogue, a “group of indigenous Mayan guerrillas launched a coordinated attack on cities and towns across the southern state of Chiapas, Mexico.” They called themselves the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista Army of National Liberation or EZLN).

In the US, debate over NAFTA centered on the impact of the trade deal on manufacturing jobs. In Mexico, among indigenous farmers, the concern was that US corn would flood Mexico.

The Zapatistas, armed with machetes and antiquated rifles, took the city hall building in San Cristóbal de las Casas that New Year’s Day. Between 600 and 2,000 Mayan guerrillas, largely between 18 and 30 years old, participated in the uprising. They read a declaration of war from the Lacandon Jungle, proclaiming “Ya basta,” which translates to “Enough is enough.”

From a military standpoint, the guerrillas did not stand a chance. But military victory was not the goal. Indeed, the military conflict lasted a scant 11 days. The real objective was to shift the balance of forces within Mexican civil society, and, as Chris Galbraith and Gerardo Ortero wrote in Latin American Perspectives, “push for democratization from the bottom up.” And while the EZLN did not achieve complete success, they did make significant gains. Arguably, the EZLN even helped propel a change in the Mexican state, as the ruling party’s 71-year control of the presidency came to an end in 2000, six years after the initial uprising.

The EZLN also lifted up a notion of democracy rooted in indigenous values and civil society. Central principles of this indigenous philosophy are the following:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Obedecer y No Mandar (Lead by Obeying)

- Representar y No Suplantar (To Represent, Not Replace)

- Bajar y No Subir (To Work from Below, Not Seek to Rise)

- Servir y No Servirse (To Serve Others, Not Serve Oneself)

- Convencer y No Vencer (To Convince, Not Conquer)

- Construir y No Destruir (To Construct, Not Destroy)

- Proponer y No Imponer (To Propose, Not Impose)

In 2001, some rights were codified. That year, Mexico’s Congress passed an indigenous reform law, later ratified in the constitution. Gains were real, but also limited. The bill said indigenous communities are entitled to “preferential use of natural resources like wood and water on their territories to meet their own needs…the right to preserve and promote Indian languages and culture, and the power to elect [Indigenous] officials according to customs that often involve a vote by an open assembly, rather than by a secret ballot.” But there were plenty of loopholes.

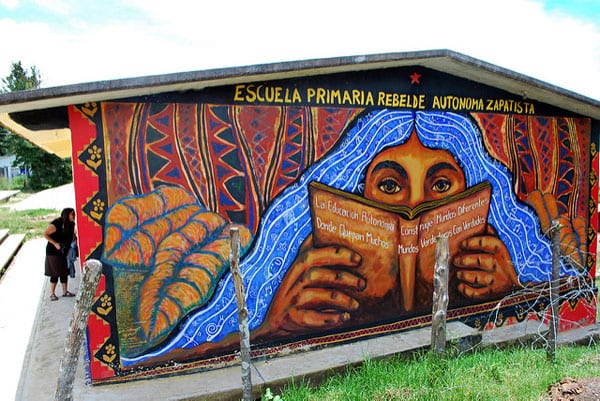

Still, even if the Zapatistas haven’t achieved all their goals, as Knoll points out, Zapatistas have run local governments in five regions that are inhabited by 250,000 people. In these regions, Knoll notes, “the Zapatistas have built schools where there were none before and provide dental and essential medical services in communities where the people before had to walk many hours to get to a doctor.”

There has also been a cultural revolution. As Knoll explains:

In 1994 an indigenous revolution was a dream for the guerrillas who launched the attack; for Zapatista teenagers today, this revolution is the only reality that they know…with their bilingual schools, workers and growers cooperatives, and independent health clinics and hold rotating volunteer roles in their government. They tell their own stories through media production, and women and men participate in the government as dictated by the women’s revolutionary law. This law was implemented shortly before the uprising in 1994 and guarantees that “Women have the right to participate in the revolutionary struggle in the place and at the level that their capacity and will dictates.” It also has clauses against forced marriage and in defense of women’s rights to work and be compensated, to choose how many children they want, and to have access to health care and education.

Meanwhile, the struggle continues: “The change we want is that one day, the people…decide how they want to live and that no group can make decisions about the lives of millions of human beings. We express this in just a few words: the people command, and the government obeys. That’s what we must struggle for,” declared Subcommander Moises in a speech marking the uprising launched 25 years before.—Steve Dubb