February 28, 2019; The Oregonian

Oregon Governor Kate Brown was hailed across the country yesterday when she signed the nation’s first statewide rent control law. The measure was hailed as a win for housing justice and a piece of bipartisan cooperation. However, it falls far short of providing a real solution for Oregon’s renting residents, and some advocates expressed concern that its shortfalls outweigh its gains.

The bill, SB 608, is 22 pages long and includes many specific provisions. Its main point, according to the media narrative, is the cap it imposes on rent increases: 7 percent per year, plus the cost of inflation. Several notable exceptions exist, including:

- Rental units constructed within the last 15 years

- Subsidized units such as section 8 housing

- Units vacated by tenants of their own accord

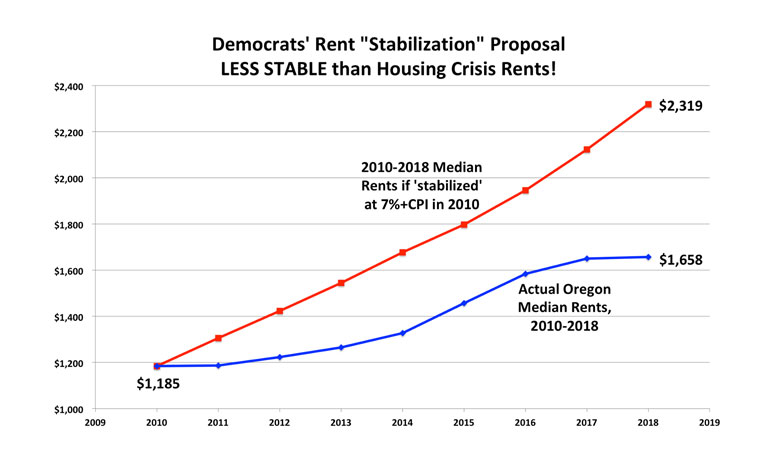

In addition to those exceptions, many observers noted that a 7 percent cap is quite high; cities in nearby California, which can impose local rent control measures, usually cap increases at the cost of inflation, which has ranged from 1 percent to 3.6 percent in Western states in the past five years. Oregon’s rule allows landlords to increase rents up to 10 percent per year. Not only is that level of increase unaffordable for many families, it’s actually a higher rate of increase than has occurred without the cap over the past 10 years.

What’s more, localities do not have the power to impose stricter controls. In some states, such as California, voters have won the right to impose municipal controls, but SB 608 maintains Oregon’s ban on such measures; Elliot Njus, who has been following this issue for The Oregonian, reports that “landlord groups…viewed [SB 608] as a better alternative to removing the state’s ban on local rent control policies.” Margot Black, a Portland tenant organizer, said, “I think it does more to protect landlords from strong tenant protection than to protect tenants from landlords.”The cap does forbid the sudden price increases that have forced many Oregon tenants from their homes, which is certainly a win; some report overnight doubling of rents. But it doesn’t do anything to increase long-term neighborhood stability.

Last June, NPQ’s Cyndi Suarez wrote about how, starting with the Nixon administration, government support for affordable housing has been cut back, leading to a dearth of supply. Governor Brown seems to agree; she called for $400 million for “affordable housing development, rental assistance and homelessness prevention” and said, “We need to focus on building supply.”

Many outlets cited economics studies purporting to show that rent control ultimately decreases the supply of affordable housing, because price controls disincentivize landlords from renting. However, NPQ’s Steve Dubb pointed out,

It sounds so obvious…except that it is not. In economics, the core neoclassical assumptions vary greatly from what we see. A well-functioning market requires “perfect information,” but anyone who has ever looked for a place to live knows that real estate is riven with uncertainty. A well-functioning market also requires perfect competition, which, due to barriers to entry, doesn’t characterize real estate either. It is hard for tenants to organize and become their own landlords, which doesn’t stop housing cooperatives from being a good idea.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A 2018 study from Stanford University found that rent control in San Francisco limited renters’ mobility (meaning it increased neighborhood stability) by 20 percent. The study also found that supply was reduced, but as Dubb points out, this is likely due to the tech boom more than to rent control.

Oregon’s bill deals with other common issues faced by renters; it includes provisions related to no-cause eviction, relocation assistance, and vacancy control. And critically, the bill is declared as an emergency, so it goes into effect immediately, giving landlords no time to raise rents before the cap hits.

However, as Portland Tenants United (PTU) argues, there are many loopholes in these provisions a well; for instance, no-cause evictions are allowed during the first year of tenancy and the language around qualifying reasons that a tenant may be evicted is so weak, it hardly protects renters at all.

PTU had a thoughtful and informative Twitter thread about SB 608, in which they highlighted tenant advocacy and called for restoration of local control over rents.

Cyndi Suarez pointed out that the movement to consider housing a basic right is only now growing in the US. Joshua Mason, an economics professor at Roosevelt University, wrote,

The real goal of rent control is protecting the moral rights of occupancy. Long-term tenants who contributed to this being a desirable place to live have a legitimate interest in staying in their apartments. If we think that income diverse, stable neighborhoods, where people are not forced to move every few years, [are worth preserving] then we collectively have an interest in stabilizing the neighborhood.

As long as the US fails to consider housing a basic right, it will be subject to the market forces that make it unaffordable for so many people. Rental units are subject to much greater price variation than mortgage rates or property taxes, disproportionately punishing those with fewer means.

Katrina Holland, the executive director of Oregon’s Community Alliance of Tenants, was dissatisfied with the bill and said, “You’d better believe we’ll be back.”—Erin Rubin