May 7, 2019; KCET

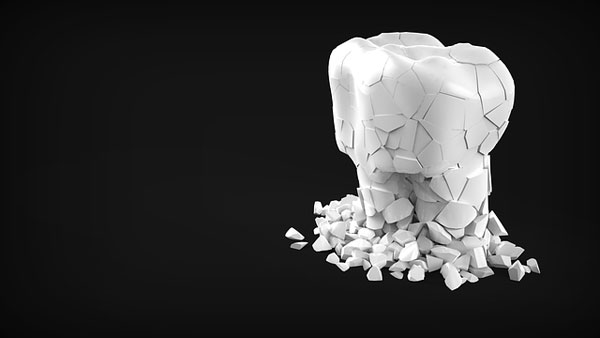

If you are looking for ways to tell a story vividly, mixing research and data in a compelling way, this story has a lot to recommend it, including a hero curator. You can tell a lot by looking at teeth, reports Kate Gammon for Los Angeles public broadcaster KCET. Gammon highlights the work of Jill Johnston, who directs the outreach program for the Southern California Environmental Health Sciences Center, housed at the University of Southern California (USC). Johnston and her colleagues developed what they call the “Truth Fairy” study. Led by Johnston, the goal was to measure residents’ past exposure to lead using baby teeth.

“Researchers,” notes Gammon, “asked residents for baby teeth from children who grew up in the neighborhoods of Boyle Heights, Maywood, East L.A., Commerce and Huntington Park. They collected 50 teeth from 43 children and analyzed them for exposure to lead and arsenic.”

All 43 children selected had lived their entire lives within two miles of a shuttered factory called Exide. The battery recycling plant, located in Vernon, south of downtown Los Angeles, operated from 1922 until March 2015. At its peak, it recycled 11 million auto batteries per year and released 3,500 tons of lead into the air. Johnston’s study aimed to “understand retrospective exposure to toxic metals using a community-driven research approach.”

Johnston decided that looking at baby teeth could help her document the impact a shuttered factory has had on community health. Gammon explains:

Johnston first came up with the idea of using baby teeth after she learned how they can provide insights into what exposures looked like five or 10 years—or even longer—ago in this community.

Blood tests, on the other hand, only show lead exposure from the past 30 days—and the Exide plant had been shuttered for years. Plus, the largely [Latinx] community living near the plant was leery of blood tests led by Los Angeles County.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The study found high levels of prenatal and early life exposure to toxic metals in the tested neighborhoods. Some of the highest exposures were found during the third trimester of gestation, when the baby is still in the womb. “Babies are growing really fast at that point…a tiny dose that affects how the cells are building has a huge effect,” explains Johnston.

The study is a microcosm of a larger pattern. Citywide, as many as 250,000 residents, mostly working-class Latinxs, “face a chronic health hazard from exposure to airborne lead and arsenic that subsequently settles into the soil,” according to a 2013 health risk assessment by the South Coast Air Quality Management District.

mark! Lopez, executive director of the nonprofit East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, was a community partner on the study. “Giving your kids’ teeth to people is weird,” Lopez concedes. “We know that folks are familiar with the tooth fairy, so we’re not slipping them a dollar, but what we can bring is truth. What we can bring is information.”

Gammon explains why the Truth Fairy approach is so effective.

Teeth grow like tree rings and incorporate lead and other metals as they add layers of enamel and dentin. The researchers can analyze each layer of the tooth for lead levels, which gives information on fetal and early childhood exposure. Each layer represents about two weeks of exposure, so it’s possible to get a fine-grain sequence of exposure data from each tooth. To study the teeth, the researchers used a high-energy laser beam (one-third the size of a human hair) that blasts a tiny hole in the tooth where the growth rings are to sample micron-level amounts of material with mass spectrometry.

Now that the data are in, the question remains how rapidly the city will address the damage. So far, according to Lopez, only a few hundred houses have benefitted from environmental cleanup.

Johnston adds, “I think the study really confirms a lot of concerns the community had about long-term exposure and what it could mean for health because of the industrial activity in this community. Even though the facility is not operating, we have legacy exposure because of the lead in the soil and dust in the community.”—Steve Dubb