February 28, 2020; Washington Post

Many years ago, nonprofit financial guru Clara Miller cautioned nonprofits to look all oversized gift horses in the mouth, a piece of advice that, it appears, might have done a world of good in the case of Family Matters in DC, which received an unexpected $28 million bequest from a single donor seven years ago after being in business for more than 130 years. Now, the organization has closed—at least temporarily—after unaccountably running annual deficits in the millions since.

Further, while this was going on, the compensation of Family Matters’ CEO, Tonya Jackson Smallwood, grew and grew until she left in 2018 after a car accident. In December 2019, the new CEO, Thomas Johnson, announced the agency would close to reorganize and promised to pay severance to those who stayed until the doors shut on January 10th. (Some of those employees are now suing the agency for breaching even that promise.) Meanwhile, even though only two staff remain at the organization, down from about 100 five years prior, Johnson contends that Family Matters isn’t going out of business. “We are undergoing a major reorganization. We have had some severe financial strains that are structural. We are looking to try to address those over the next two to three months.”

Johnson also tried to attribute the losses to Smallwood’s absence from the agency following her accident, which appears to be past when the horse had already left the barn. Within a year of receiving the bequest, the organization was losing money, contracts, and other funding relationships.

Is all of this surprising? Not so much. We won’t delve too deeply into the rest of what limited information is currently available, but want instead to call attention to Miller’s basic financial physics advice.

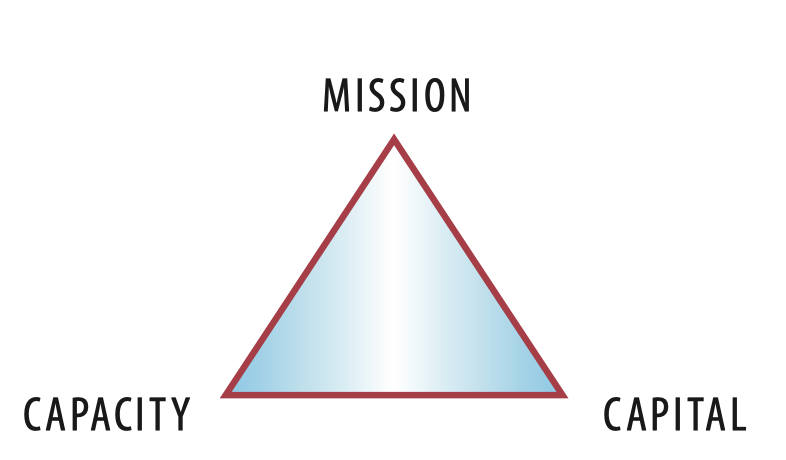

For all nonprofits, sustainability means keeping the balance between mission, capacity, and capital. If one changes, the others must change to maintain balance within the enterprise. These fixed relationships in a dynamic system might be described as “the laws of gift physics,” where the impact of matter (gifts of varying kinds) introduced into an existing system (an organization) gives rise to certain predictable results. To some extent, in a gift system, every action has an equal—and opposite—reaction. Under these rules, each gift to an organization has an impact that exerts pressure on other parts, forcing the others to adjust to the impact of the first. Here is our familiar triangle where mission, capacity and capital exist in equilibrium.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

If any one side of the triangle changes, the other two must change. This takes place whether it is planned or not, whether the giver intends it or predicts it or not and, above all, whether anyone wants it to happen or not!

Miller goes on to write that there are particular problems posed when the money is restricted or illiquid, but in the Family Matters case, neither issue seemed to be at play. Rather, it appears that the organization threw caution to the wind with its new cushion, observing none of the red flags that should have alerted decision-makers to core problems along the way.

On at least two occasions, staff at Family Matters sued, saying they were fired after raising concerns about financial malfeasance. One federal lawsuit was filed in 2015 and dropped in 2016, and another was filed in 2018 in DC Superior Court, only to be settled later that year after being moved to federal court. Yet the organization went on losing millions.

“Employees were intentionally kept in the dark by Defendant Johnson as to the organization’s declining fortunes,” said the suit, which seeks unpaid wages and three months of severance and insurance benefits. “Many of the employees…could tell that something was seriously wrong.”

I guess we could ask the age-old question “where was the board?” and add to that, “where were the funders?” But now, as the agency prepares to reorganize after leaving staff and service users in the lurch, one must also wonder why the organization does not just pay its obligations and transfer its remaining assets to another agency that does the same type of work. Because when you run through cash in this way, especially in the context of doing direct service, you also run through your credibility.—Ruth McCambridge