September 11, 2019; Commonweal and Wall Street Journal

Last month, two wealthy and charitable men, Bernard Marcus and John Catsimatidis, writing an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, strongly advocated for individual action and the power of the free market as the path to improving our society. From their perspective, the wisdom of successful individuals is greater than the collective wisdom of a democratic government. They strongly believe that those who are successful in business—those who are wealthy—are most capable of solving complex social problems.

We know we can spend our dollars more wisely, and in ways that benefit our communities and our country, than politicians can…When we look at the way government spends its money, we are frustrated by the waste and the ineffectiveness of so many of its programs, however well-intentioned. The projects we fund of our own accord deliver real bang for the buck. The schools to which we donate teach kids better than many rural and inner-city government-run ones do. Our enterprises better promote values associated with virtue and success, and they are helping cure terrible and painful diseases from cancer to multiple sclerosis.

Theologian John Chryssavgis, writing in Commonweal, challenges this assumption that private action can rise to the occasion.

To suggest that wealthy donors can replace government programs is both arrogant and dangerously irresponsible. Private philanthropy falls off during economic downturns, when poverty rises. In other words, philanthropy tends to be cyclical, whereas public programs are designed to be counter-cyclical, helping the most when there’s the greatest need for help. The idea that faith-based or privately organized charity is more efficient or more effective than government relief has not been true since the industrial revolution. It is especially untrue during a recession.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Even as the generosity of Marcus, Catsimatidis, and millions of other donors, big and small, has pushed overall charitable giving in the United State higher, the amounts raised pale in the face of the need. It is notable, for example, that even in international development, where philanthropies like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation play an outsized role, their grants still pale in comparison to the contributions of government. As NPQ noted, while US foundations gave $35.4 billion in the year 2011–2015 period, official development assistance totaled $778.6 billion—22 times as much.

As Chryssavgis observes, “No matter how dizzying the donations of the wealthy…it is a fantasy to believe that voluntary organizations, including religious ones, could adequately replace the array of government health and social programs that help the most vulnerable.”

For Marcus, Catsimatidis, and all who share this fantasy, however, the gap between charity and need will be closed by successful businesses that harness the “win-win miracle of the free market.” (Anand Giridharadas has some choice words about “win-win.”) In its revised Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation, the Business Roundtable defined their role in the marketplace: “Businesses play a vital role in the economy by creating jobs, fostering innovation and providing essential goods and services.” The resources necessary to finally overcome the problems long plaguing our society will come from a business environment “that provides an opportunity for all to move upward “the old-fashioned way,” which Marcus and Catsimatidis see as a simple formula available to all: “We had bold plans, we took big risks, and we built and invested in highly successful made-in-America businesses.”

The defense of wealth and the wisdom of the financial elite rings hollow. Government programs may have inefficiencies and scandals, but so does private business. Both are features of human endeavor. The successes of one person and the travails of another are often less a matter of personal qualities than of chance, privilege and inherited advantage. Allowing societal answers to be reached through a series of individual choices is likely to lead to dead ends and further harm.

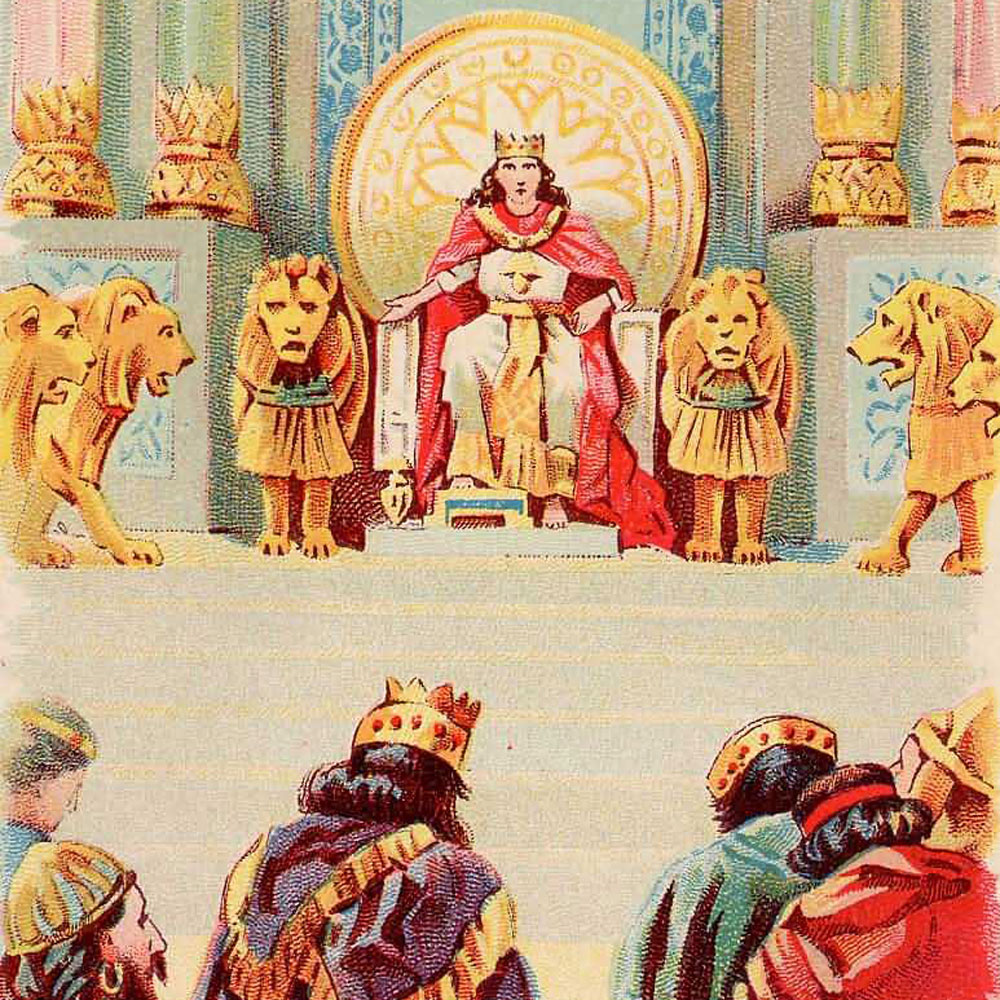

What is needed is not the belief in the wisdom of a self-crowned elite to save us, but an understanding that democracy, as imperfect as it may be, calls us to act affirmatively on the public’s behalf.—Martin Levine