December 13, 2019; Associated Press

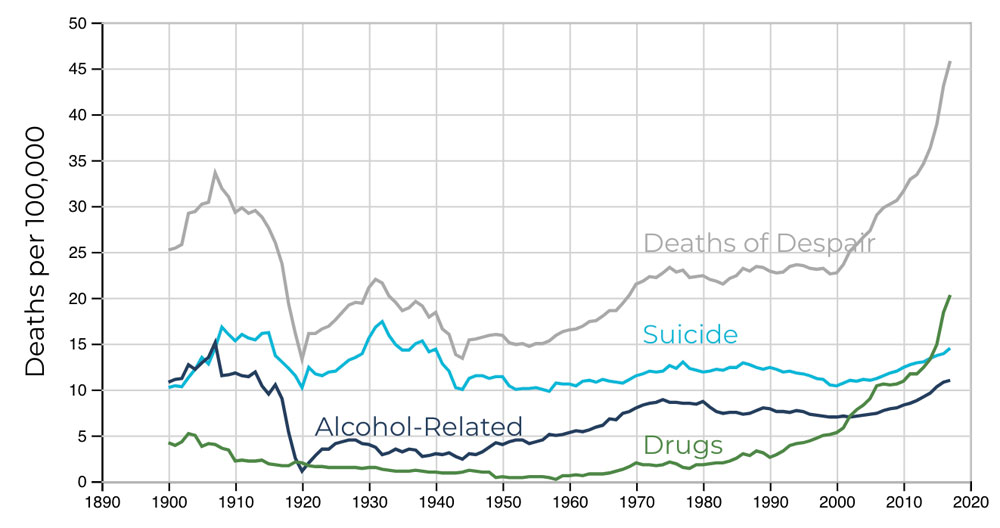

Three demographic data points tell us something is seriously wrong in our country. Unlike every other highly developed nation, US life expectancy has declined for the past three years. For two decades, America’s young and middle age residents have seen their mortality rates increasing, fueled by spikes in suicides, drug overdoses, and obesity. In 2018, the birth rate hit a three-decade low. Why is this happening, and how should we respond?

If we were seeing the effects of a new disease, maybe we would be looking for new drugs and vaccines and beefing up our care systems. But that’s not what we are now facing. Rather, a changing economy and failed public policies are having a direct impact on longevity and overall health.

Steven H. Woolf, director emeritus of the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, whose study of mortality rates was recently published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), sees the growing number of deaths among people at midlife as a sign of something larger than a specific medical issue. He told the Washington Post last month, “The fact that that number is climbing, there’s something terribly wrong.”

Ellen Meara, a professor at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, was even more explicit when she told the Post, “There’s something more fundamental about how people are feeling at some level—whether it’s economic, whether it’s stress, whether it’s deterioration of family. People are feeling worse about themselves and their futures, and that’s leading them to do things that are self-destructive.”

The data regarding life expectancy and early death are stark. According to the JAMA study, “US life expectancy has not kept pace with that of other wealthy countries and is now decreasing…during 2010–2017, midlife all-cause mortality rates increased from 328.5 deaths/100,000 to 348.2 deaths/100,000. By 2014, midlife mortality was increasing across all racial groups, caused by drug overdoses, alcohol abuse, suicides, and a diverse list of organ system diseases.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While earlier data had suggested that the rise in midlife deaths, now termed “deaths of despair,” was concentrated in white working-class communities, recent findings show its effects on black and brown populations as well. Economic disruption, isolation, and fear of the future do not discriminate.

As the data mounts and our understanding of the root causes grows, the impact of the lack of effective, fact-based, and comprehensive policymaking becomes clearer. As with the climate crisis, we are struggling to accept what experts know is true and take effective action to reverse negative health impacts.

Typical of the difficulties of taking on the societal malaise that is deeply affecting our lives is the challenge of combatting obesity. According to S. Jay Olshansky, a public health professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, “Most people in the United States are overweight—an estimated 71.6 percent of the population age 20 and older.” Combatting this would take a robust effort to educate the public, ensure everyone has access to more healthful foods and has the funds to put them on their table, and challenge producers to reduce the amount of sugar in their products. Every one of these steps is difficult and means entering the battlefield where we now form public policies.

Going beyond symptoms to deal with systemic causes is even more difficult. A recent Associated Press article focused on the growing death rate of midlife adults in one state, Minnesota. It underscored the underlying issues—economic insecurity and income inequality—that must be faced to reduce overdoses, suicides and other preventable deaths.

As Steven Woolf noted in comments reported by Vice, the “lack of social programs and support systems for working families is a major reason why Americans are dying younger. Without a safety net, rough spells can lead to so-called deaths of despair that involve drugs, alcohol abuse, overeating, or other harmful behaviors…the prescription for the country is we’ve got to help these people. And if we don’t, we’re literally going to pay with our lives.”

For the nonprofit sector, these findings may not be very surprising. We work on the ground, taking care of those whose lives are directly affected. Many of our organizations work to prevent suicides, respond to the drug abuse epidemic, and attempt to ease the burden of difficult economic changes. But however well we do our jobs, the data show we are still losing ground. What’s needed is policy change, the kind that sees the comprehensive nature of our problem and is ready to rebuild trust in facts and fact-based solutions. We need policies that recognize that a strong safety net makes individual lives better and benefits everyone. Without that, our sector will continue to be stretched, and many of us will be living shorter lives.—Martin Levine