May 19, 2020, New York Times and Labor Notes

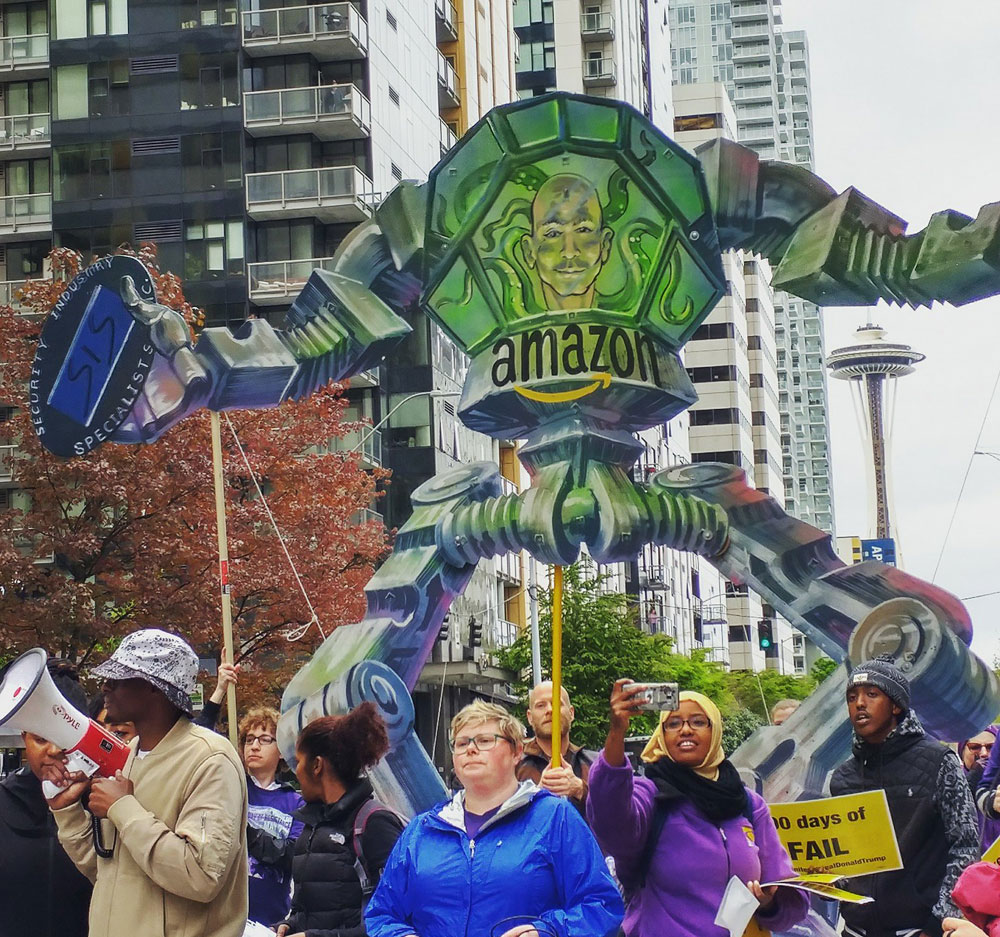

The inhumane “damned if you do” choice essential workers face is no guarantee for sufficient protective gear, time off to recover from sickness, or higher pay. Amazon, whose founder and CEO Jeff Bezos has grown his wealth by $34.6 billion in the past two months, is a stark example of one such workplace.

Amazon workers across the country have witnessed COVID-19 infections occur and spread at their separate workplaces. Those rallying to the banner of Amazonians United declared on May 11 that they were “organizing for the long haul.” The workers’ aims include preparing to meet “the most severe forms of retaliation,” which indicates a confrontational relationship with management. In such a hostile environment, basic worker protections—let alone higher pay—must be fought for and won.

This is a workers’ movement, albeit one unaffiliated with established labor unions, speaking up to improve working conditions, like those at a delivery center in Chicago asking to get water in the summer heat. A group of workers in Sacramento united to demand paid time off for part-time workers and that a fired coworker be reinstated.

The group engages workers to “assess their own issues” and organize to derive the means to negotiate for workplace improvements.

This New York Times article about Amazon’s biggest COVID-19 outbreak to date chronicles the rising rate of new infections among workers while the company’s response to making the workplace safer lagged. As cases at the Pennsylvania warehouse rose to eight, a worker alerted the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) that they had to bring their own disinfectant, writing, “The richest company in the world can afford to close for a few days with pay for their people.”

OSHA closed this particular complaint after Amazon provided documentation of what they did in response; operating with the smallest number of inspectors since 1975, OSHA has eased enforcement of existing rules and started “asking employers to investigate themselves.” However, infections kept rising. Eventually, after mid-April, Amazon stopped releasing numbers. When employees asked why the company stopped sharing infection data, managers told them “it made no difference” and they “didn’t want to make employees fearful.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Amazon finally did disinfect the facility, change work procedures, hire additional workers, and require masks. Still, the Amazon employee whom the Times interviewed said that the company responses were “just way too late.”

This Reuters article quotes Amazon warehouse employee Jana Jumpp, who concludes based on reports from Amazon workers nationwide that at least 800 workers have tested positive and at least six have died. (Amazon had nearly 600,000 US employees in 2019.) This picture contrasts with statements from Bezos to shareholders, reported by the Guardian, that the company was going to spend at least $4 billion of their profits on coronavirus-related expenses such as getting products to customers and “keeping employees safe.”

The Guardian also included the following quote from Derrick Palmer, an Amazon employee at a warehouse in Staten Island, New York: “Right now, Amazon workers are very depressed. We feel like it’s either stay home and let bills pile up or go to work and possibly get sick.”

Amazon had revenues of $75.4 billion in the first three months of 2020. Through his Amazon stock holdings, Jeff Bezos makes $2,489 per second, or a staggering $8.96 million per hour. In contrast, the average base pay of Amazon warehouse workers is $15 an hour, which, as a percentage of Bezos’s earnings, works out to 1/597,360—or 1.674 × 10-6. Such extreme inequality in a command-and-control, employer-employee relationship may make building trust impossible.

The grotesque income disparity tips even more a scale already favoring Amazon, #28 on Forbes’s Global 2000 list of the world’s biggest public companies and the largest retailer in the world. The punishing balance of power makes winning worker rights in this context not just an uphill fight, but a long battle against enormous odds. Severely weakened federal compliance oversight in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic aids the company, adding a heavy burden to labor struggles.

Amazon’s workers are building solidarity for the long haul. Though their organizing chops have been helping them make demands around COVID-19, they will need more support to make gains. What is civil society called to do in this context? Standing in solidarity with workers, and refusing to accept that a decent quality of life is out of reach for an increasing number of us might be our moral imperative.—Kori Kanayama