April 21, 2019; New York Times

With little data to demonstrate the effectiveness of an online learning system, the Kansas Department of Education selected two rural school systems as pilots for the Summit Learning platform. It’s not going well.

Summit is one of the more recent educational reform experiments to be backed by a billionaire and resisted by public school parents, who are often seen as recalcitrant blockades to bright ideas from on high. Mark Zuckerberg began to support Summit in 2014, devoting five Facebook engineers to the project, and since 2016, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has committed just under $100 million to the project.

In Kansas, where schools are struggling under Republican tax and education policies, implementing state-of-the-art, web-based, student-directed, student-paced curriculum seemed to be precisely what the towns of Wellington and McPherson needed to raise their test scores and improve their schools.

Proponents of the Summit Learning system argue it offers students more control over the content, as they can determine the speed at which they learn and when they feel comfortable taking tests. Teachers using the system do not have to administer or grade quizzes and tests, leaving them more time for personal interaction with students. The Summit Learning software provides teachers with a broad range of data about student performance, and the curriculum is continually updated.

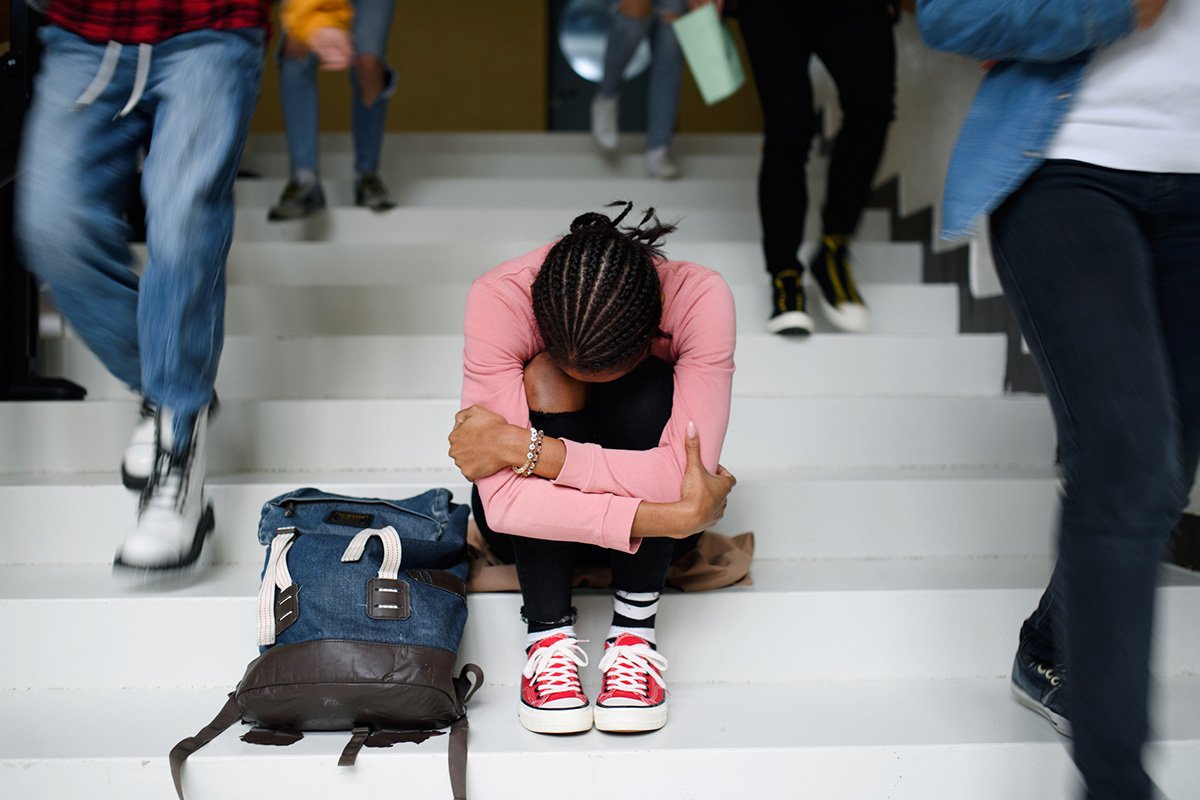

The realities of web-centric learning appeared shortly after the program’s implementation. As Nellie Bowles’s article in the New York Times notes, “Students started coming home with headaches and hand cramps. Some said they felt more anxious…another asked to bring her dad’s hunting earmuffs to class to block out classmates because work was now done largely alone.”

Web-based learning forces children to spend hours a day on computers, a requirement that dramatically exceeds the American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines (AAP) for Electronics for School-Age Children. Obesity and sleep disturbances are the most benign of the potential problems children with too much screen-time face, according to the AAP. And screen-time’s not the only issue that concerns parents. The software collects a large amount of personal student data, building an electronic file for the duration of the student’s participation in the program. Many parents are worried that the privacy language contains too many loopholes that might eventually allow the data to be sold or misused. Privacy concerns were a primary driver for schools in Cheshire, Connecticut, to suspend the program in 2017. (We expressed our concerns about Summit back in 2016.)

In fact, Bowles writes, the program has been invited to leave more than one community:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The resistance in Kansas is part of mounting nationwide opposition to Summit, which began trials of its system in public schools four years ago and is now in around 380 schools and used by 74,000 students. In Brooklyn, high school students walked out in November after their school started using Summit’s platform. In Indiana, Pennsylvania, after a survey by Indiana University of Pennsylvania found 70 percent of students wanted Summit dropped or made optional, the school board scaled it back and then voted this month to terminate it. And in Cheshire, Connecticut, the program was cut after protests in 2017.

Summit’s CEO, Diane Tavenner, started developing the software in use by the company in a series of charter schools she founded starting in 2003. Her view is that the resistance is fueled by nostalgia. “There’s people who don’t want change. They like the schools the way they are,” she says. “The same people who don’t like Summit have been the sort of vocal opposition to change throughout the process.”

But the truth is that, once again, the communities in Kansas resisting this change may not want to have their children be harmed by a process which is unproven.

Summit chose not to be part of a study after paying the Harvard Center for Education Policy Research to design one in 2016. Tom Kane, the Harvard professor preparing that assessment, said he was wary of speaking out against Summit because many education projects receive funding from Mr. Zuckerberg and Dr. Chan’s philanthropic organization, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

What’s more, the curriculum itself has come under fire because it links to items some parents find questionable. One Kansas father was displeased to find that a unit on Roman history linked to a website a few clicks away from sexually explicit art. Parents in Kentucky objected to the presentation of content about Islam as contrasted with that on Christianity. States like Kentucky have school district-based curriculum assessment where the public, teachers, and administrators review and approve materials, and many parents are not interested in having that power curtailed by someone “on the web.”

John Pane of the RAND Corporation studies personalized learning and the use of digital tools. He believes electronic teaching is in its infancy and “there has not been enough research.” Apparently some parents in Kansas would agree.—Skip Lockwood

Corrections: This article has been altered from its initial form due to new and updated information. The student whose seizures increased as a response to increased web-based screen-time was not using the Summit platform.